We all take drugs. And all drugs pose risks: from medications prescribed by your doctor to that Smirnoff Ice at last call. But if you ask most people to describe the stereotypical drug user, it’s rare for anyone to hold up a mirror.

A middle-aged gay man who snorts the occasional line of coke at a party may think he has little in common with a homeless woman turning tricks and smoking crack in an alley just a block away. Still, in the face of a conservative social and political tide, more people are realizing that when it comes to drug use and sex work, we need to reduce the harms associated with these activities instead of trying to curtail them.

Whether it’s the ongoing fight in Ottawa to maintain a crack-pipe distribution program, or the constitutional challenge intended to decriminalize the sex trade, a harm-reduction approach rejects the idea that prohibition is a useful way to approach sexuality or drug use. And at a time when queer politics don’t have a clear rallying point — but rather a scatter of issues both local and national vying for our attention — we have much to learn from the lessons of harm reduction.

When it comes to drug use, not everyone understands harm-reduction philosophy. After all, shouldn’t addicts aim for abstinence instead?

It’s a question often put to Adam Graham, a prevention worker at the AIDS Committee Of Ottawa who works specifically with gay men.

“If someone is using drugs in a way that makes their life too chaotic and consequently decides that they are in a position to reduce their harm enough to self-initiate recovery? Good on them,” says Graham. “It would be extremely irresponsible — and dangerous — for public health officials to offer only one solution to people in our community. Harm reduction works for some of us, treatment works for others.”

Graham’s perspective acknowledges that things aren’t always so simple. Not everyone wants or needs to quit using drugs. But for those who do, defeating an addiction can involve years of effort and many setbacks — even if you have access to recovery professionals, a network of supportive non-using friends, and a safe, secure and comfortable place to live. But many addicts — especially those with mental-health challenges, or who are poor or homeless — lack all of these comforts.

And supporting someone to use in a safer way can keep them healthy until they are better equipped to stop using successfully.

“You can’t get off drugs if you’re dead,” states Anne Livingston of the Vancouver Area Network Of Drug Users (VANDU), in the poignant documentary Fix: Story Of An Addicted City. The film chronicles the political battle that birthed InSite, a safer-injection facility in the poverty-sticken Downtown Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver.

At InSite, drug users can inject in a clean and well-lit environment under the watchful eye of medical staff — instead of picking up used needles off the ground and using dirty water from the gutter to prepare their fix. The site garnered international acclaim and scientific studies proved its benefit to the health of users and the community — but despite all the evidence, the Harper government has yet to confirm that the centre can remain open beyond Dec 31 of this year. Meanwhile, the City Of Ottawa has turned its back on crack smokers, in a decision that could have deadly impact if allowed to stand.

Ottawa on crack

Smoking crack in the nation’s capital achieved a countrywide high profile after a weekend Globe And Mail exposé back in April warned that Ottawa had experienced an “explosion” in the drug’s popularity. Recently elected conservative mayor Larry O’Brien told the Globe it wasn’t too late to take action to address the problem. And indeed, before too long he and suburban city council colleagues took aim at downtown crack users.

On Jul 11, Ottawa city council voted 15-7 to terminate its safer-inhalation program, which used some city funds to create safer crack-use kits. Along with condoms, lube, lip balm and health information, each kit included the makings of a glass pipe with a protective rubber mouthpiece.

Many crack smokers employ dangerous handmade pipes — often fashioned from discarded pop cans, asthma inhalers or broken ginseng bottles — cutting and burning their mouths and hands in the process. As a result, users are at higher risk for acquiring or transmitting HIV or hepatitis C either from sharing the pipes or when performing oral sex.

A 2007 study by Montreal’s public health department indicated that over 60 percent of injection drug users have hep C — and other research has shown that more than 80 percent of injectors also smoke crack.

HIV and hepatitis C (HVC) can be a dangerous combination. Having HIV can cause HVC to multiply eight times faster than normal — and anti-HIV medications can negatively affect the liver, worsening the impact of hepatitis.

For a cost to the city of $7,500 a year, Ottawa’s chief medical officer of health Dr David Salisbury estimated the crack-pipe initiative could save millions in future health-care costs because of disease prevention.

The epidemic of HCV infection among drug users is a public-health crisis — and safer inhalation programs are a key part of the solution. Dr Lynne Leonard, a social epidemiologist with the University of Ottawa, carried out research demonstrating the success of the program in reducing pipe sharing — as well as converting drug users from injection to a less-risky alternative: smoking it. Similar health initiatives are in place across Canada in cities including Halifax, Whitehorse, Winnipeg, Guelph, Vancouver, Montreal and Toronto.

Quitting handing out pipes will not stop anyone from using crack, especially since homemade pipes are so easy to make — but it will prevent users from protecting one another by doing so more safely. And support agencies say it will drive the marginalized practice further underground, severing a vital link between crack smokers and health workers.

Nicholas Little is an outreach professional with the AIDS Committee Of Ottawa.

“I hand out crack kits ever single day,” says Little, who argues that ending the program will have a catastrophic impact. “Users won’t come see us anymore. That means I can’t help them find housing, or get jobs, or access a shelter, or get into treatment if they want to get off drugs or reduce their use.”

Little says politicians are toying with people’s lives and he feels there is a strong role for queer activists to play.

“The queer community needs to advocate that safer inhalation be mandated at a provincial level — so municipal governments can’t dismantle health programs based on ideology,” says Little.

Little and Adam Graham tend to tag-team on these issues, especially when it comes to advocating for the program. Graham echoes Little’s anger at council’s decision.

“Ottawa city council hasn’t got a single leg to stand on with the baseless conviction they used to yank funding from the crack pipe program, yet those of us who use crack and those of us who work in public health have both our own experience and now science on our side.”

Little is sympathetic about the level of drug use in the queer community.

“The prime motivator to use drugs is just to cope with all the fucking bullshit that we live with everyday.” Queer youth are vulnerable in particular, he says.

“Queer youth face hostility and violence at high levels, in the school system and at home. Many are chased out of their homes and live on the street,” Little points out. His anger at the situation is palpable. “I don’t think anyone could really say that if they found themselves in that situation, they might not also turn to substance use to cope with the pain.”

Harm is relative

Few would deny that crack addiction can have harmful consequences. According to the Safer Crack Use Coalition (SCUC), a Toronto-based advocacy group, the health impact of chronic crack smoking can include heart and blood-pressure irregularities, serious respiratory infections and “doing the chicken” — blacking out while experiencing uncontrollable body twitches — which can sometimes result in sudden death.

But the drug generates pleasure as well — a rare respite for users whose lives are already marked by poverty or mental illness. For many, crack use is the least of their worries.

Chris Gibson, a program director at the Toronto men’s hostel Seaton House, explained it this way, speaking before a federal government special committee on non-medical drug use: “Drugs create feelings of well-being. Stopping drug use is going to allow them to wake up every day and be clearly aware of that fact that they have no education, they have nowhere to live, and they have limited prospects — which seem like really good reasons to use drugs.”

Law-enforcement officials will tell you drugs like crack are illegal because they’re harmful to users and society. But the reverse is even more true — some drug use is harmful specifically because of the fact that it’s against the law.

For instance, needle use can lead to many more health problems than inhaling a substance — such as abcesses, endocarditis (a potentially fatal heart infection) and a greater risk of overdose and death. But if you can be arrested for getting high, many people will choose the route least likely to be detected — and shooting up generates no telltale smoke or odours.

One of the biggest harms of all associated with addictive drugs is their economic cost. It’s easy to link illicit drug use and criminal acts such as theft — after all, both are considered morally suspect in the public imagination. But most addicts wouldn’t steal if illegal drugs — produced and distributed via underground economies fraught with risk — were not so unfairly expensive. In this way, drug laws set up a cycle of incarceration that wouldn’t otherwise exist.

Connor McCullum is the hepatitis C coordinator for Prisoners’ HIV/AIDS Support Action Network (PASAN). He works men and transwomen in federal prisons — where condom availability is poor, and needle and crack-pipe distribution is prohibited. Drug-related harm is an even more serious issue behind bars.

“A homemade syringe will pass through the hands of literally hundreds of people,” he points out.

“People do everything in prison that they do outside — they have sex, they get high, they get tattoos — but they are forced to do it much less safely.” McCullum says medical staff in jails support harm reduction but their efforts are thwarted by prison authorities. This tension between health experts and law enforcement is mirrored on the streets as well. According to Dr Leonard’s report, about 25 percent of Ottawa crack users had their pipes taken away from them by police officers — who in some cases smashed them on the ground to destroy them.

Queers and harm reduction

“The gay community understands harm reduction — but only when it comes to sex, or club drugs,” says Walter Cavalieri, director of the Canadian Harm Reduction Network.

“But AIDS — which first united the gay community — is about more than just sex. It’s also about injecting drugs and using crack. Many AIDS organizations deliberately marginalize drug users, and it makes me angry.”

Cavalieri is a gay man and a harm-reduction pioneer. He spearheaded one of Canada’s first needle-exchange programs at Toronto’s Parkdale Community Health Centre.

“Street people won’t join organizations perceived as gay because they face enough stigma already.” He adds, “I understand why gay organizations avoid drug users — they are perceived as difficult. But we all need to try harder.”

PASAN’s McCullum agrees.

“Drug users are ‘queer enough’ when we’re having sex with them — but not when they’re getting arrested for using drugs or when they have to sleep in a park,” he says.

Harm reduction is relevant to queer politics because some of us are homeless, sell sex or use drugs. But it goes beyond that, too.

The vast majority of same-sex loving people around the globe are unable to be open about being queer. The very act of coming out is one of the most basic forms of harm reduction. Mere decades ago, queers in Canada faced some of the same forms of widespread stigma experienced by drug users today — we were considered morally deficient and targeted in medical and social discourse as diseased.

At the outset of the AIDS epidemic, we knew that abstinence wouldn’t work — so we fought to keep bathhouses open and pioneered community-based safer-sex education instead.

Safer-sex efforts prevent the spread of HIV. So, we use harm reduction in the gay community to promote safer sex.

But sexual harm reduction doesn’t end with defending HIV-negative folks. People with HIV deserve reduced harm too. This means access to treatment and efforts to defend against other infections. Protection from harm for people with HIV also includes the right to determine if and when to disclose their status to others, including sexual partners.

The gay-liberation slogan “we are everywhere” is as true of the crack house and the street corner as it is of the corporate boardroom. And the philosophy of harm reduction forms a logical middle ground between the mainstream and anti-assimilationist conceptions of queer politics — because it advocates looking at people’s lives as they really are, rather than wishing either that we could be just like everybody else or that we overthrow the system.

In the meantime, Walter Cavalieri has some advice for Ottawa’s Mayor O’Brien — that he spend a couple nights with the people distributing safer crack pipes on city streets. “Be humble. And listen.”

Good advice for us all.

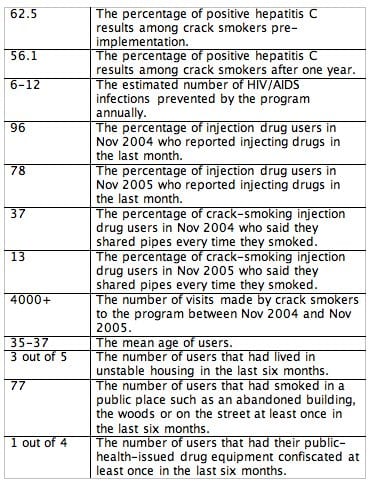

By The Numbers:

What the University Of Ottawa study showed:

Figures from Dr Leonard’s findings.

City Of Ottawa Public Health Safer Crack Use Initiative.

Released Oct 2006.

www.medecine.uottawa.ca .

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra