No caption Credit: xtra files

no caption Credit: Xtra file

NO caption Credit: Xtra files

no caption Credit: xtra files

no caption Credit: xtra files

no caption Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

Credit: xtra files

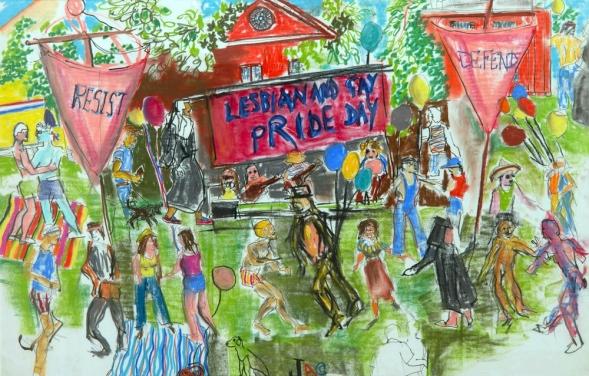

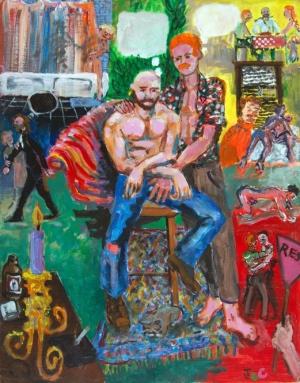

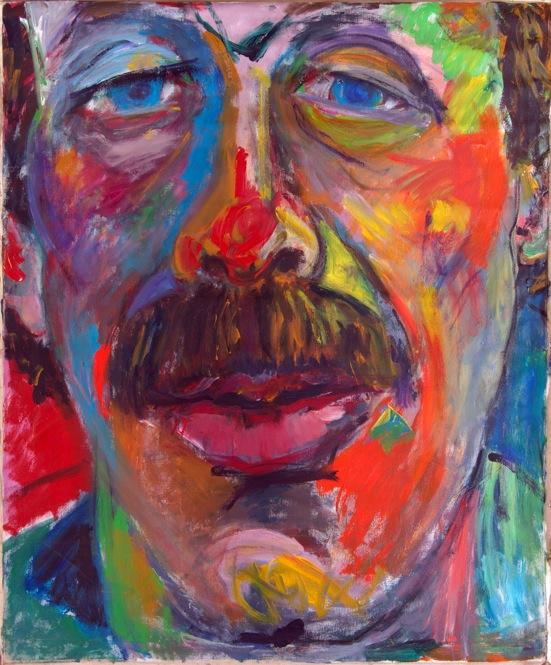

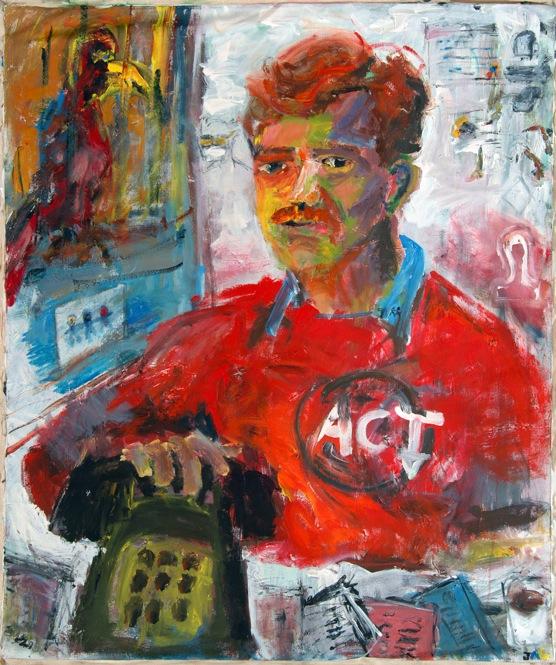

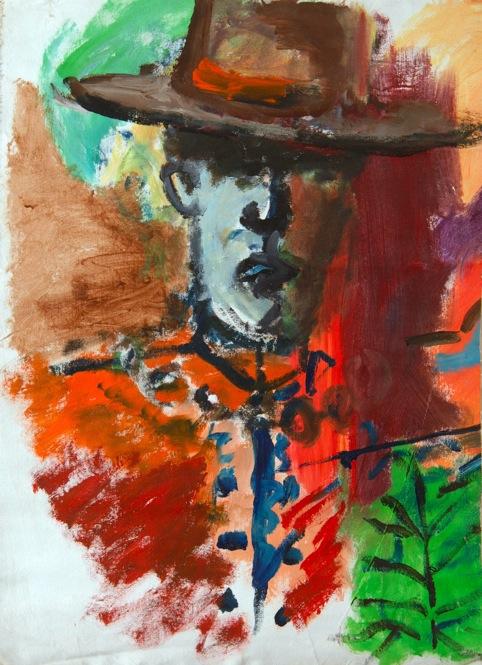

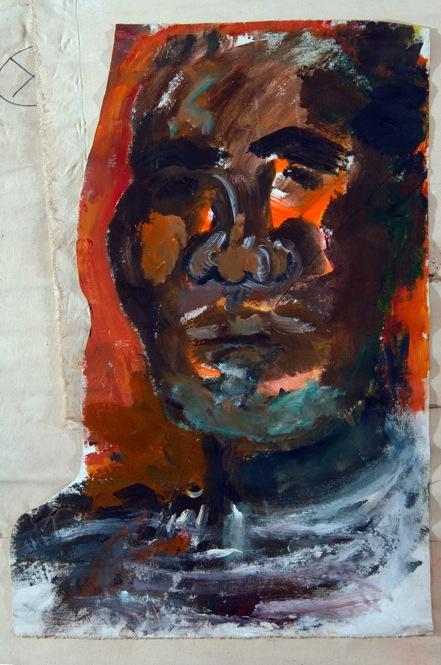

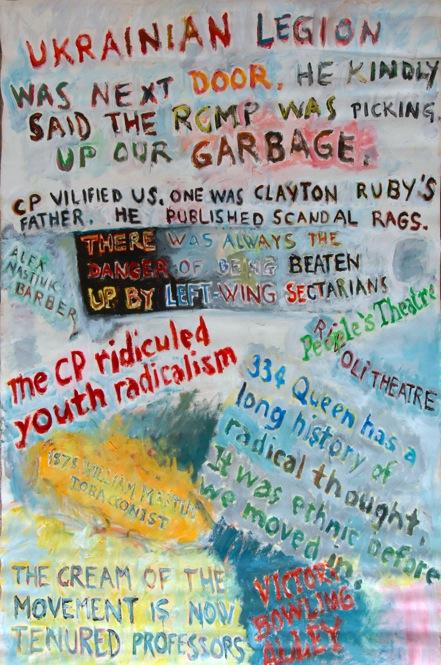

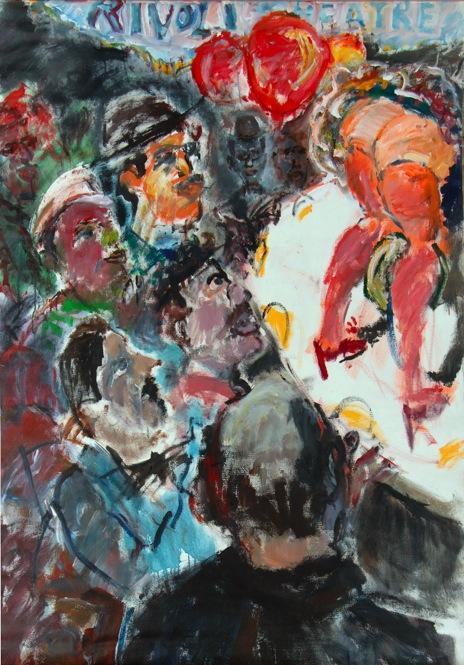

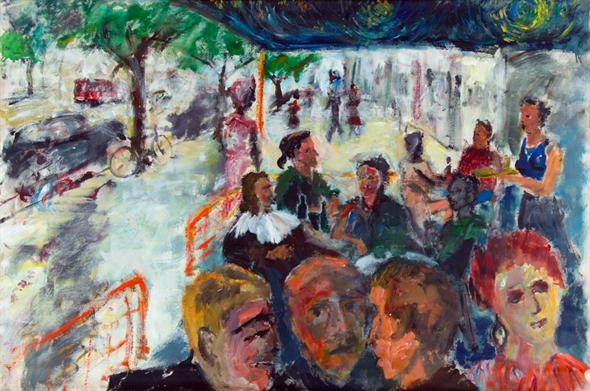

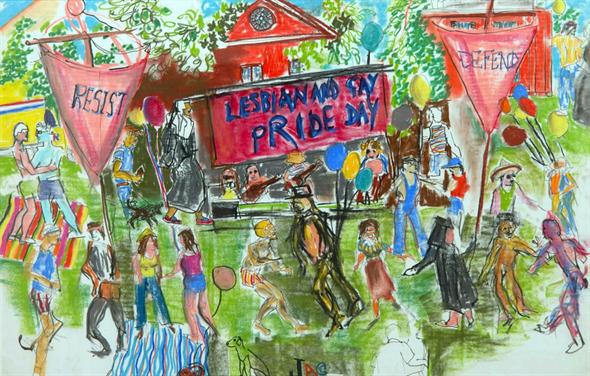

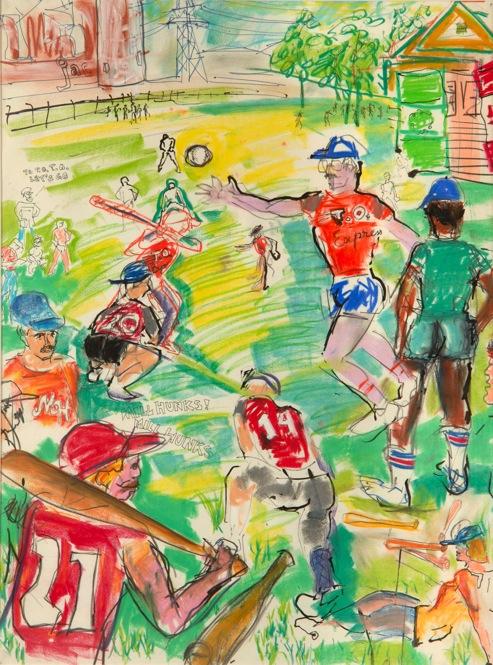

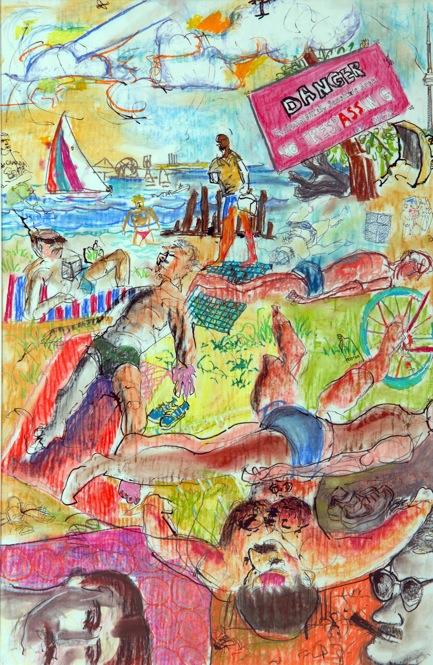

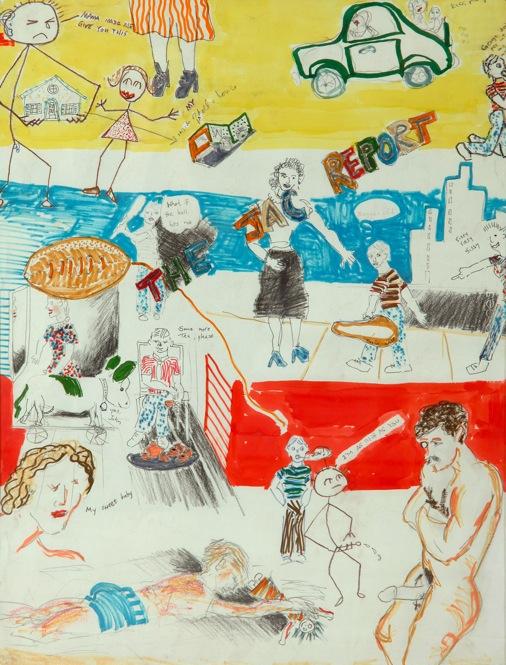

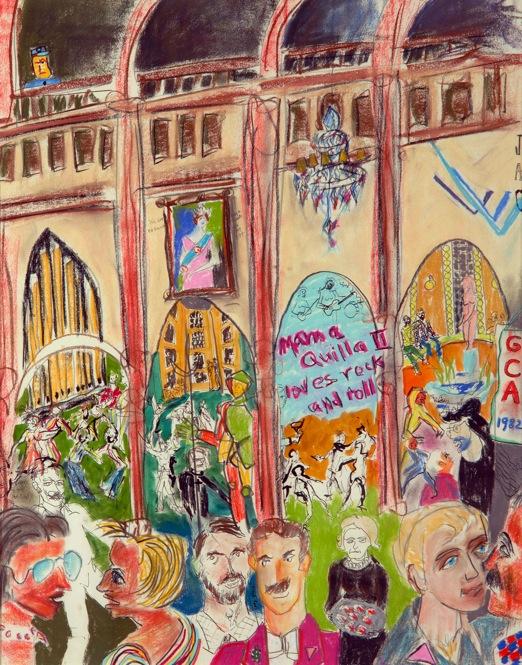

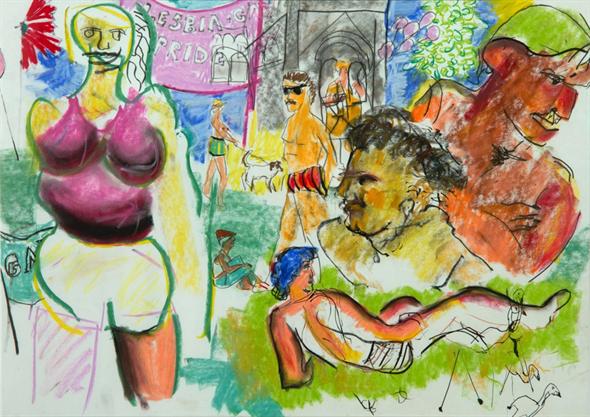

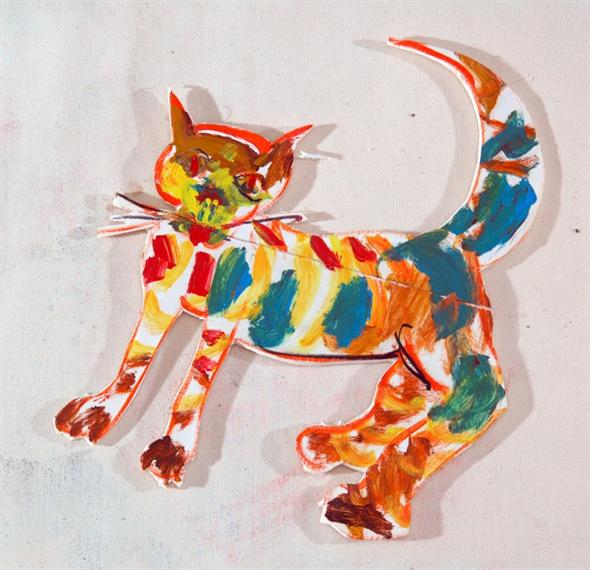

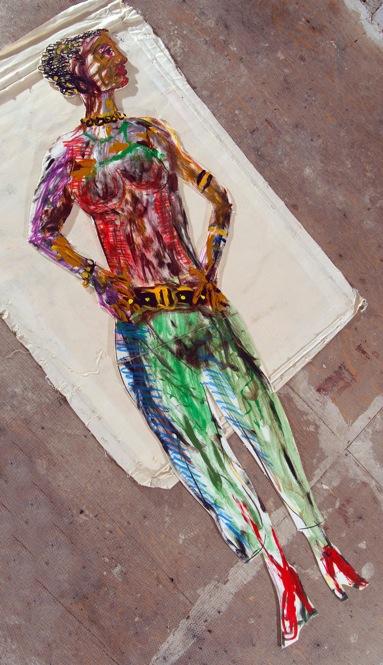

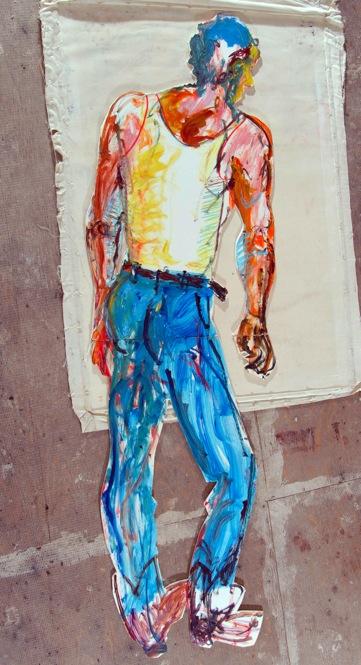

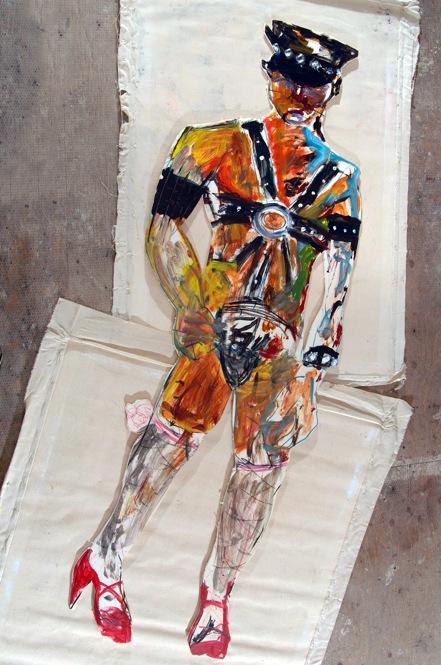

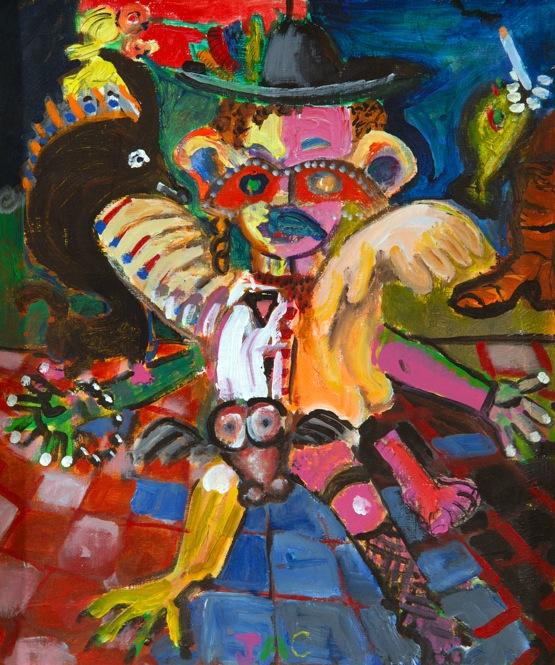

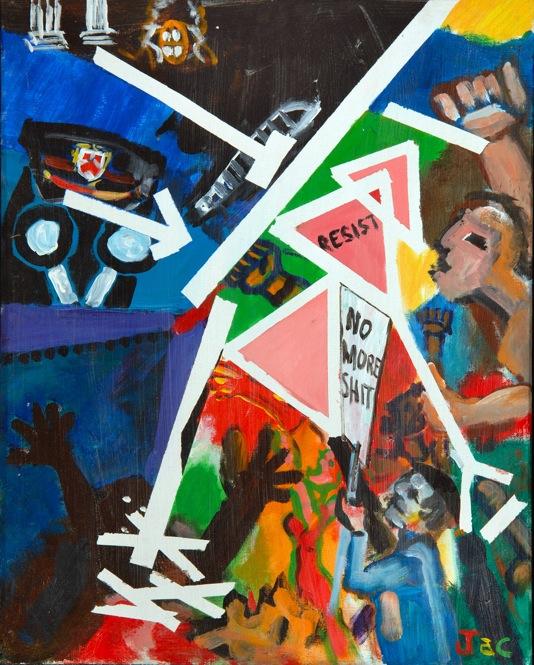

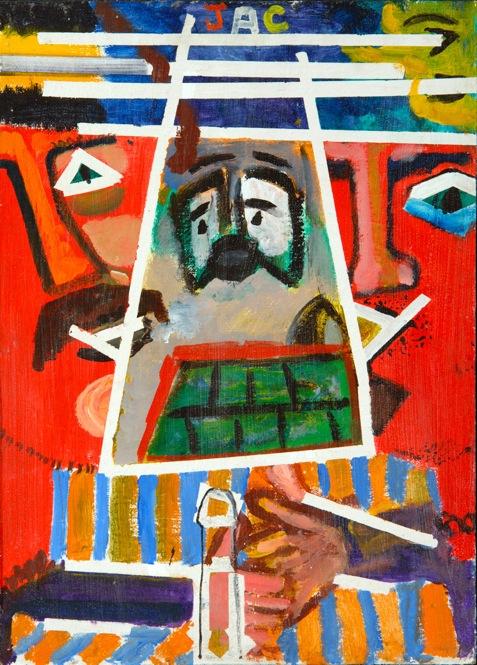

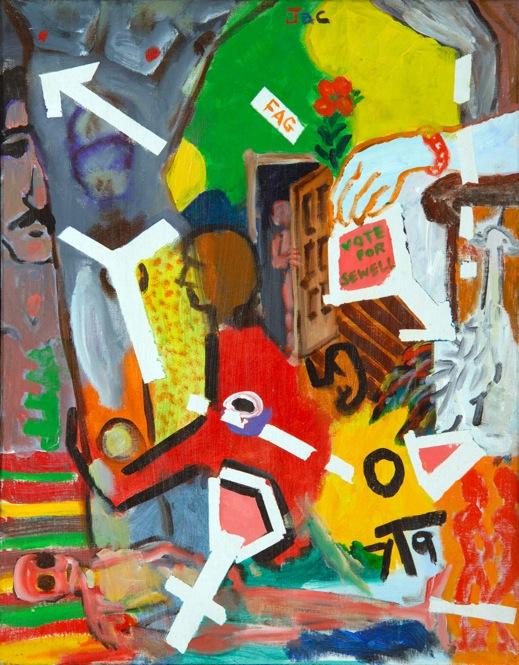

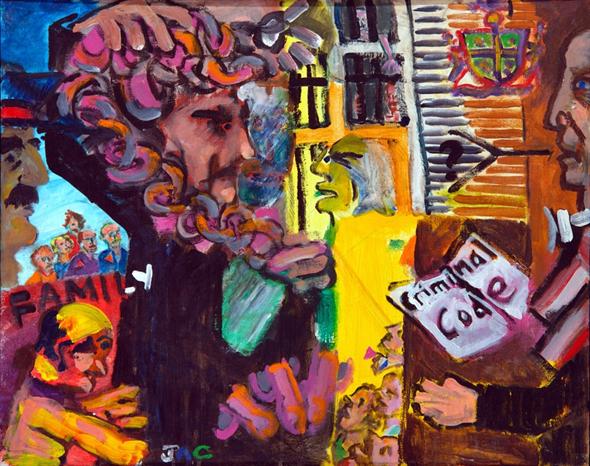

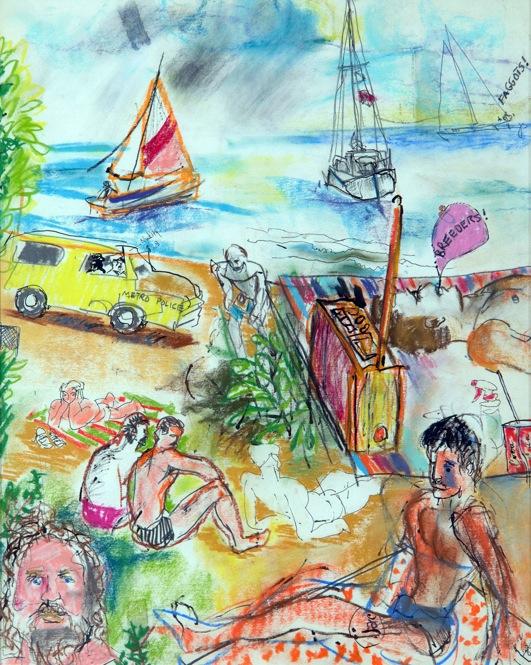

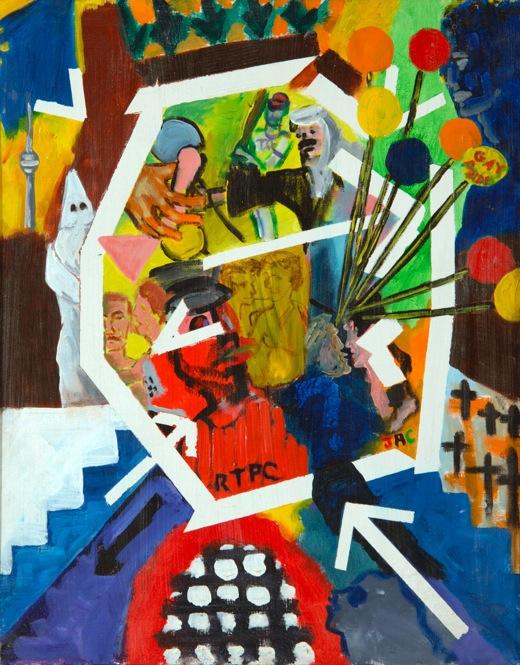

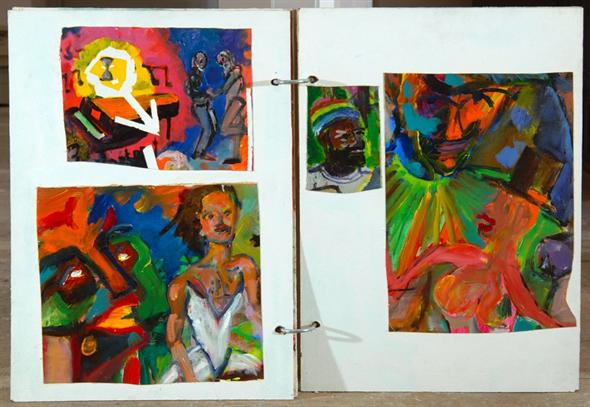

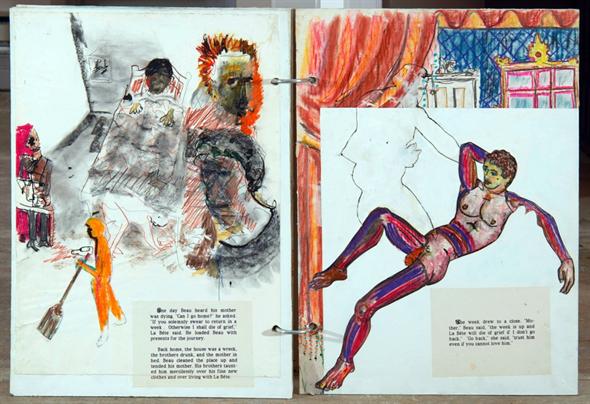

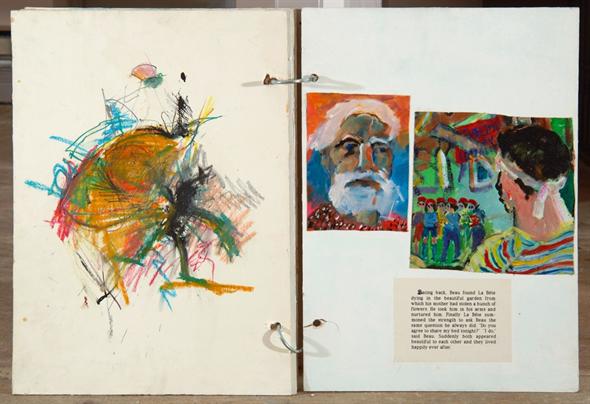

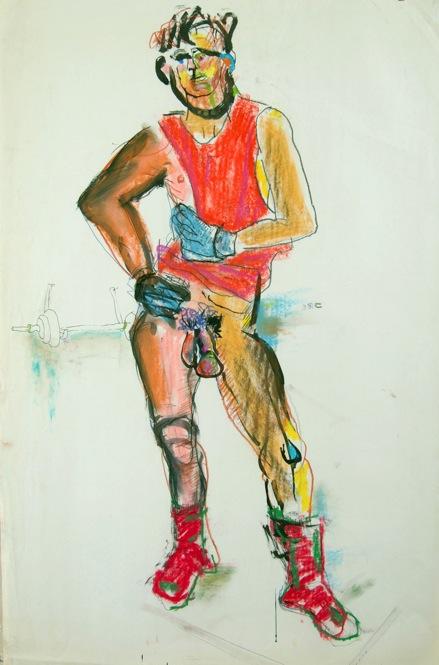

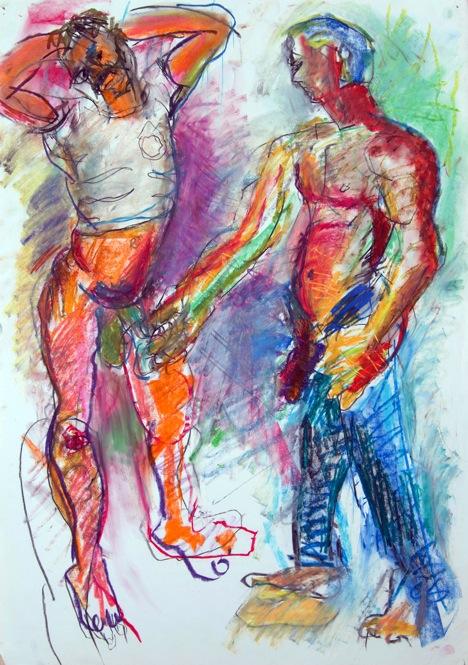

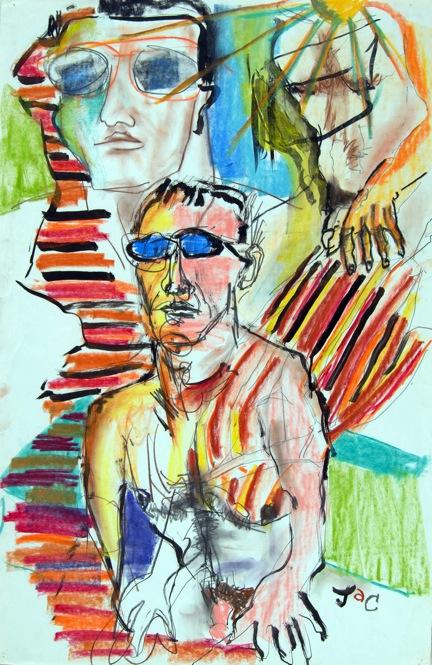

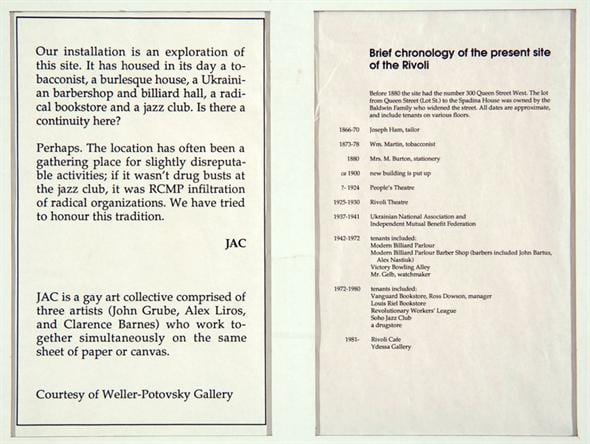

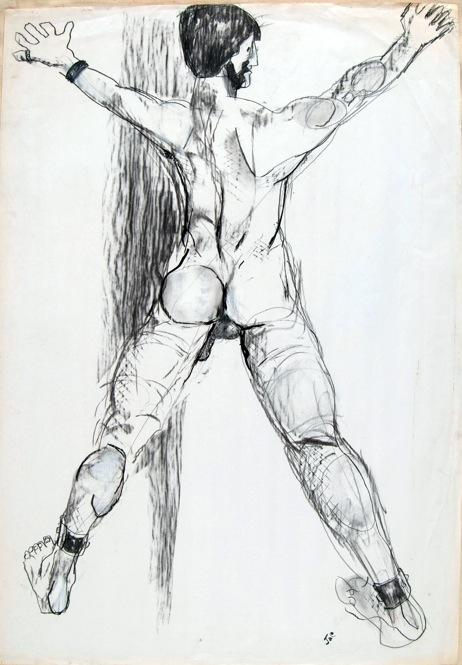

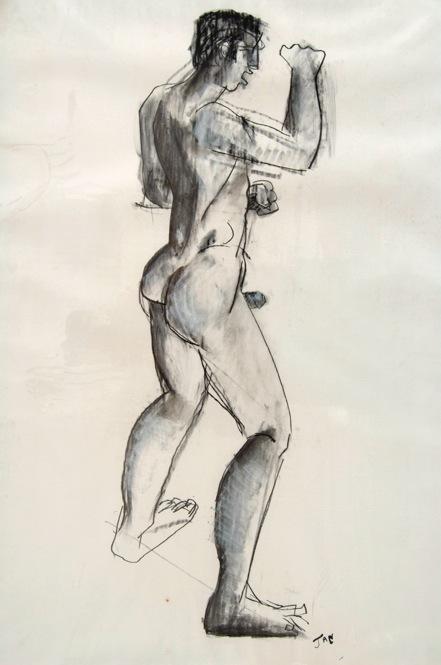

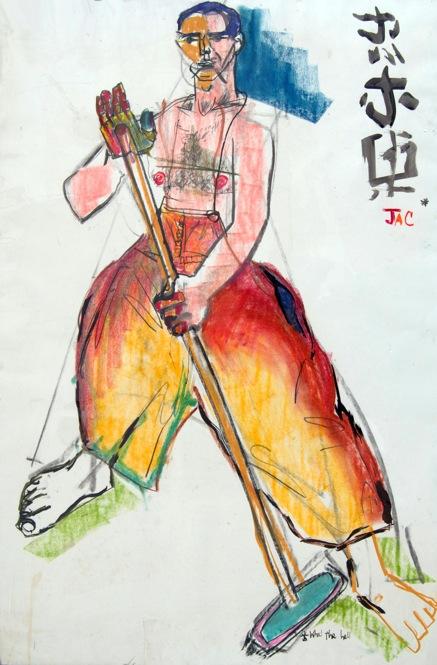

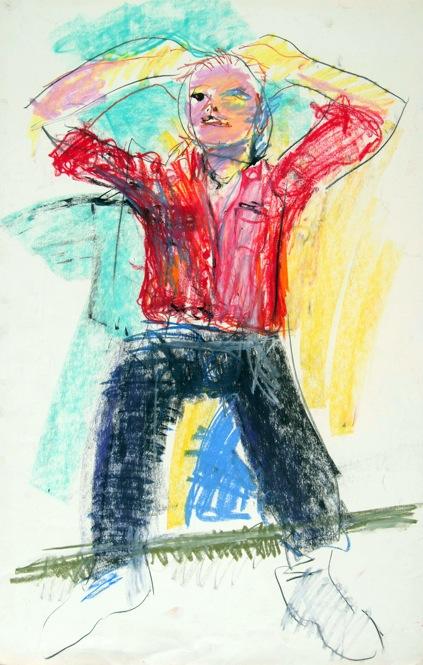

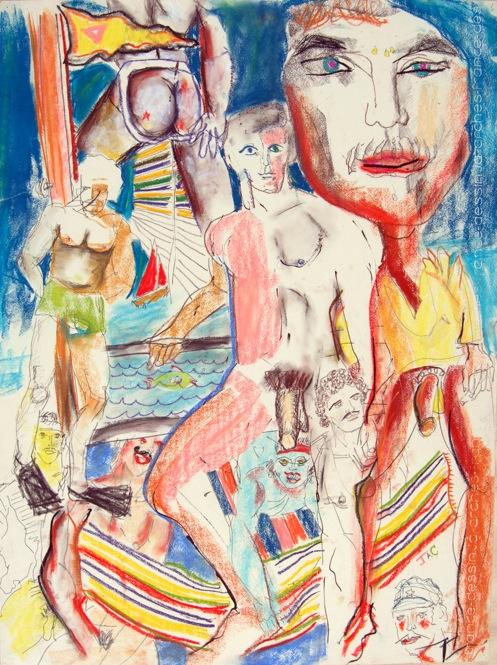

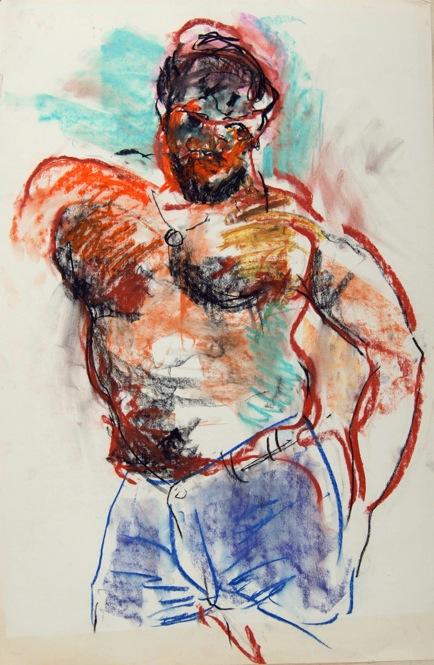

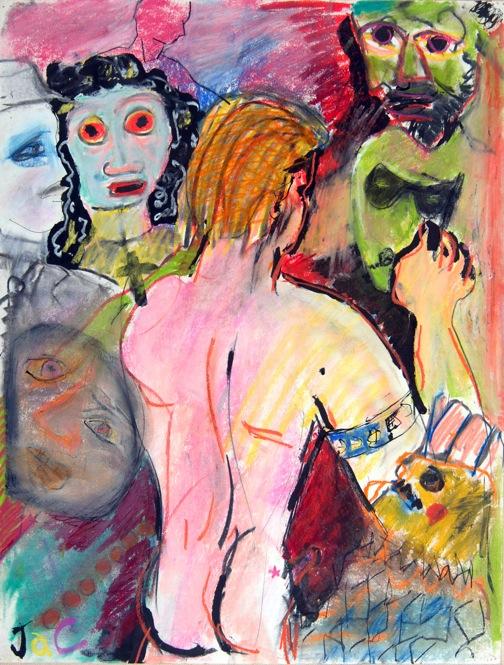

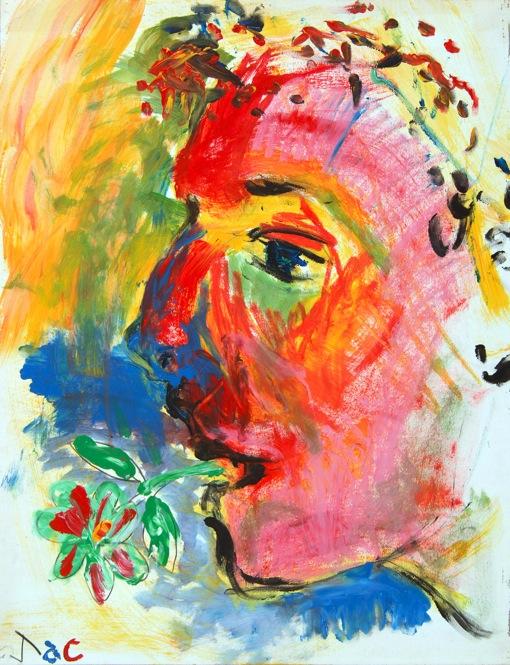

Alex Liros is a Toronto-based artist and former member of the JAC art collective (1980-1988). Liros worked alongside fellow artists John Grube and Clarence Barnes to produce large-scale group paintings that members worked on simultaneously (the name JAC is an acronym of the artists’ first names).

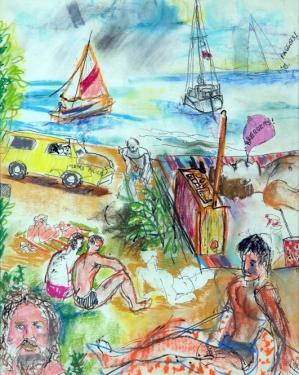

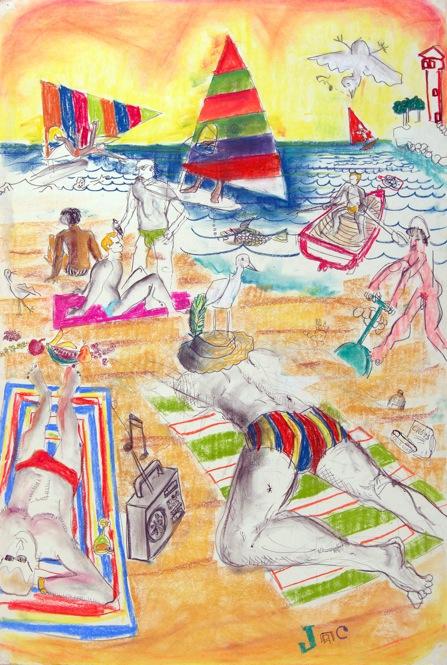

Their work details a wide range of themes in Toronto’s gay community, including the struggle for freedom in the post-bathhouse-raid era, early Pride celebrations, popular gay hangouts, celebrity and sexuality.

For the first time ever, these paintings and dozens of others are available at Xtra.ca, with an audio tour by Liros. Grube and Liros gave the collection to Pink Triangle Press, Xtra’s parent company. Watch the video below (an audio/photo tour in 10 parts, roughly 10 minutes each), or read the entire transcript (PDF).

Audio interview of Liros by Jon Lidolt. Digital images captured by Gilberto Prioste. Slideshow produced by Brent Creelman.

***

You can also check out the JAC collection at your own pace — click the image below to launch a gallery of 150+ images:

For more on Alex Liros, visit his website alexliros.com.

More on the

JAC collective, written by Daryl Vocat:

Where have queers come from? Where are we now? The work of the JAC Collective invites us to think about history and community, chronicling a spirit of resistance filled with joy, creativity and triumph.

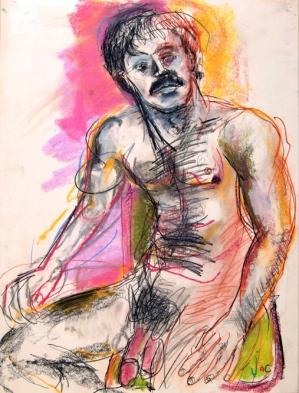

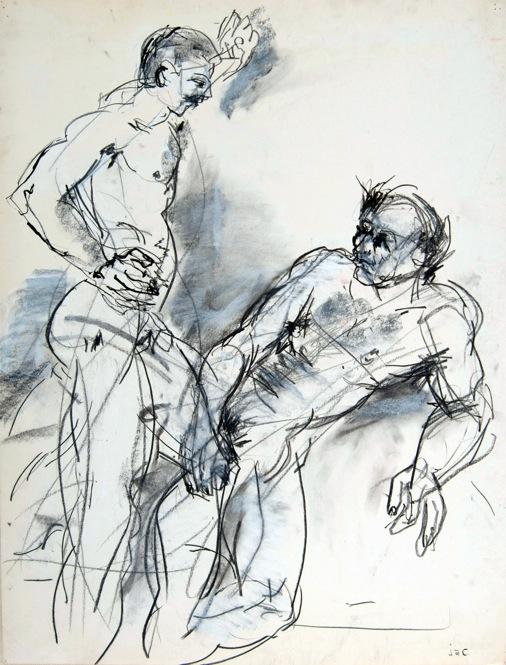

“JAC” was John Grube (rhymes with ‘tuba’), Alex Liros and Clarence Barnes, a trio of Toronto artists whose collaboration began with GAI (Gay Art Involvement), a group that began to meet weekly to draw the male nude in 1980.

Its members felt this exploration was missing from mainstream art practices. Everyone who attended the meetings shared the cost of the models. GAI members felt that the looseness implied by the word “involvement” appropriately defined their activities and described themselves as having “a lack of formal structure combined with a sense of groping, however tentatively, toward a joyously gay art.”

On one of the regular GAI drawing nights the model didn’t show up. The artists improvised with what they had on hand: three men and a porn magazine. They decided to experiment with each other, and JAC was born.

According to Grube, “Alex Liros suggested that we work simultaneously on the same sheet of paper,” an idea he got from an exercise at art school. At first the experiment was awkward, disjointed and marked by territorial grudges about who drew over whose work. Grube describes their early work as “textbook illustrations of the art of the insane.” Thanks in part to their sense of humour, the trio persisted; working together became a more unified process.

What started as a simple experiment turned into an eight-year collaboration, complete with the joys and strife of making overtly gay political art in Toronto during the heyday of gay liberation.

Over the years, Grube became JAC’s voice. He had taught creative writing at the Ontario College of Art and Design, the University of Victoria and the University of Windsor. He also had number of books under his belt. Grube died at 77 in 2008.

Alex Liros initially took art classes at the Ottawa School of Art and over the years worked as a part-time librarian. He frequently exhibited at Toronto’s Gallery 1313 in Parkdale.

Clarence Barnes, who died in 1995 at the age of 61, was a full-time lecturer in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Toronto. He was involved in the Gay Academic Union in the 1970s, the JAC Collective in the 1980s and Gays and Lesbians Aging in the 1990s.

The three men worked together as JAC from 1980 to 1988. They wanted to investigate the idea of gay art: Who makes it? Who consumes it? And what exactly is it? JAC explored these questions by examining some of the iconography and stereotypes common in gay male art practices: Naked men, jockstraps, construction workers and athletes.

Rather than duplicate the work of other gay artists, JAC aimed to document and explore the community from which these icons arose. Emphasizing art as a social endeavour, JAC transported their art supplies to community events and documented the people around them. In their own words, “JAC not only depicts the traditional cock and balls, but is also to be found sketching outdoors… trying to give visual expression to a growing sense of gay community.”

Grube recalled, “At one GCDC [Gay Community Dance Committee] fundraising dance we brought our easel along and set it up in the middle of the dance floor. Everyone passing wanted to make his or her mark! To participate in creating the lively disco dance on paper.”

The group was also known for its public drawing sessions at events such as Gay Pride in Grange Park, and at Hanlan’s Point — then a nude gay beach — on Toronto Island.

JAC exhibitions included shows at Toronto’s Idée Gallery in 1982 and at Gallery 44 in 1983, as well as a handful of other solo shows, group shows and lectures. Although JAC had work shown in Chicago (the third Annual Gay American Arts Festival in 1982), Ottawa (Gallery 101 in 1983) and Halifax (the Centre for Art Tapes in 1986), their presence was most widely felt in Toronto. They were a community-based collective, documenting the city in which they lived.

Visibility is a key component of JAC’s work. They depicted the people and the lives of the gay community to counter gay stereotypes and build that community. They created and documented history as it was lived. Not waiting for mainstream culture to portray the lives of queers, JAC busily worked to make their own version of culture, one in which they were recognized.

One of the curious things about JAC’s work is that on very nearly all of their publicity materials they prominently stated that they were “a gay art collective.” Back in the 1980s, proclaiming gayness was a much more dangerous, political undertaking than it is now. Even today, describing something as “gay art” remains an easy way to marginalize or dismiss it. If it appears to be destined for a gay audience, then everyone else can keep on ignoring it.

Former art gallery owner Dennis O’Connor has a thing or two to say what constitutes gay art and what gays think about it.

“The central defining difference between gay people and straight people is sex,” says O’Connor. “Gay sex is the basis for our history of discrimination and our struggle for rights and inclusion, and this is reflected in our art… By labelling and celebrating gay art, we protect our unique niche within the greater society.”

Similarly, the collective recognized the power of claiming a label for themselves and being proud of it. Every time JAC came out, they took a chance.

Their strategies produced works displaying a confection of people and places, from the dance floor to the softball field and from the courtroom to the bedroom. The drawings, often flat and disparate, express a sense of community, hope and vibrancy. Densely peopled and bombed with colour, they seem alive.

But some of the works could be described as eyesores. For JAC, intention and process were as important as aesthetics. As Clarence Barnes once wrote, “We took our self-imposed responsibility as gay community artists seriously and the price we paid was often to be dismissed as either a freak show or just Sunday painters.” JAC never became famous, but they stuck to their ideals.

Seen as radicals, the collective would not evoke warm feelings in everyone. In a scathing review published in 1983 in the Ottawa Citizen, Nancy Baele described their work in these terms: “derivative and banal, the show is a cheap travesty of the intentions of true art.” She went on to say that their work was difficult to relate to. But JAC’s work was not intended for the Nancy Baele’s of the world.

Just as not all reactions to JAC’s work were overflowing with puppies and rainbows, so there were also problems inside the collective. The intention to work collaboratively in a non-hierarchical fashion is admirable. However, conflict is a near inevitability. Conflict in the collective appears to have taken a very organized form, complete with group meetings, detailed notes and even the creation of operating rules.

In-fighting in activist groups is nothing new. On one hand, it’s reassuring to understand and share our pitfalls, knowing that others have had similar experiences. But on the other hand, it’s a depressing fact that these roles have been played out so many times before. Suffice to say JAC members had different ideas on how they should work together and on how power and relationships in a collective should work. This is the joy and the terror of living and working in the margins, as JAC did: There are no rules of conduct and no answers. Their persistence in working together for eight years despite their problems must be commended.

The JAC collection houses manifestations of lofty ideals. It is a collection of art that attempts to document and to agitate a community, to question and to communicate, to create a more passionate, colourful and just world.

Writing about the 2000 JAC exhibition at his gallery, O’Connor summarized the significance of the show in these words: “The JAC exhibition is important to me because as we further our collective history, we must continually renew our connection to the struggles and victories that brought us here today. It is an opportunity for the existing community to educate gay youth, who have grown up disconnected from our culture.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra