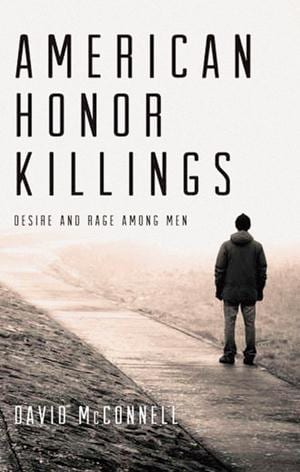

David McConnell's book documents six murder cases in a way that has some critics drawing comparisons to Truman Capote's In Cold Blood.

New York author David McConnell’s latest book is a brutal read. In American Honor Killings: Desire and Rage Among Men, he chronicles six cases of men who killed men because they were gay.

As much as I’d like to think I’ve got a high threshold for details of violent crime, as I read through McConnell’s 256 pages, I had to stop at certain moments, put the book down and take a break. McConnell researched these cases extensively, then sat down with the murderers in jailhouse interviews so he could learn more about their motivations and reflections years later. The result is a harrowing bit of creative non-fiction, each case retold and examined thoroughly, complete with McConnell’s cogent analysis and first-person accounts of the crimes.

And they are grisly. McConnell goes one step further in titling his book American Honor Killings — honour killings being a classification of crime usually reserved for developing nations, where women (or gay men) are killed for purportedly bringing dishonour to their families. McConnell suggests provocatively that the men he spoke with committed their crimes because they somehow felt the men they killed had dishonoured them.

Exhaustively researched and full of haunting detail, McConnell’s book is drawing comparisons to the landmark 1966 “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood, penned by legendary gay scribe Truman Capote. But amazingly, McConnell says the idea for American Honor Killings was not his own. “It was suggested to me by an editor as a quick true-crime book,” he says, from his New York home. “I’d never done anything like it and agreed simply because I wasn’t working on anything else at the time. I started out thinking I could nail it easily, then I slowly became fascinated and horrified as the importance of the subject matter dawned on me. I was obsessed. So I thought I’d try to make it something much more ambitious — as serious and honest a book as I could possibly write.”

Early in the book, McConnell analyzes a high-profile case of homophobic murder, the fatal shooting of Scott Amedure by Jonathan Schmitz in 1995, after their appearance on the tabloid TV program The Jenny Jones Show. (The crime was famously called “The Jenny Jones murder.”) McConnell points to the crime as the “only authentic instance of gay panic,” in a chapter in which he convincingly argues that such a legal defence has rarely worked and is even more rarely authentic. “I think ‘gay panic’ is an idea that’s gotten stuck in a lot of people’s heads. Some killers may even explain their actions to themselves that way. But as an acceptable legal defence it’s dying out, if it ever really worked. Even as long ago as 1968, Ramón Novarro’s hustler murderers failed to get off with a gay-panic defence.”

But McConnell says that “people still cling to gay panic as a concept. Like so many slogan-sized ideas we use to explain the world, it doesn’t explain much. I wanted to shift the characterization of these crimes away from both ‘gay panic’ and ‘hate crime.’ Whether we like it or not, those terms absolve the killers to some extent, because crime seems more understandable when it’s committed under the influence of extreme emotion like panic or hatred. And my research shows that just isn’t true. There’s calm, a decision, a perverse rationale behind these crimes that makes them far more horrible than we realize.”

Of the cases McConnell examined, he found little evidence of the theory that extreme homophobia must come from people who are repressing those feelings themselves. “There seems to be some truth to this but not as much as people believe. Only one of the six cases I write about involved a killer who was definitely gay. It doesn’t seem to matter whether the murderer experiences revulsion for the feeling or the mere idea of homosexuality. Plus, to me, treating these crimes as inevitably the work of screwed-up gay people feels dismissive. More often the murderers are screwed-up straight people.”

McConnell concedes he was daunted by the inevitable comparisons to Capote. “I realized early on that I was trying to do something similar to what he had. He’s a writer I adore, and maybe being skittish about influence, I didn’t reread In Cold Blood. I wanted to write something artful, but the times have changed enormously since In Cold Blood, and ‘non-fiction novel’ just isn’t an acceptable form today. Doubts about Capote research have unsurprisingly upset some people. Since I had to be a lot stricter with sources and facts, I guess ‘novelistic non-fiction’ is a better description of what I ended up with.”

And yes, McConnell confirms that meeting and interviewing convicted murderers did make for some strange moments, in particular one rendezvous with a man on death row in San Quentin. “They lock you in a tiny cage together, so there’s no way to get out. I didn’t like that. We were both really nervous, just the way you’d be when you were first meeting anybody. So, as if it were a kind of first date, he started by telling me this long story about how visiting procedures had become ultra-strict since an inmate had attacked his visitor with a shiv a while back. He told me the story in all innocence, not deliberately trying to scare me. Just the opposite. This was a big, threatening guy doing everything he could to seem mild and harmless and intellectual — just for the sake of my company. But it did make me a little nervous.”

And then there was the case of a prisoner who sent pictures to McConnell’s cellphone. “He used a contraband cellphone to text me photos of his hand cradling his homemade shivs, as well as ‘pumping iron’ pictures of himself. I think he’d had success intriguing people that way before. I just acted cold, but I found it very unnerving to have my cellphone ping in the course of ordinary daily life and then find pictures like that on it. He was later caught with one of his phones and put out of circulation for six months or so. Cellphones are a huge problem in some of these places.”

When asked what disturbed him the most about researching a book about such horrific crimes, McConnell says simply that it was their basic extremity. “I guess the most shocking thing is simply that people really do kill. That doesn’t seem like much of an observation, but for most of us killing is a plot point on CSI: Miami or in an old Agatha Christie book. We’re really very innocent, for the most part, about the dark corners of experience, which, when you really look at them, aren’t dark corners at all. Rare as they are, murders do happen, and there’s no spooky music to set them off from ordinary life, no narrator elbowing you in the side about a ‘dark corner of experience.’ I had the chance — and the burden — to meet and interact with these murderers as men. This was deeply disturbing, and I think it’s probably changed me.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra