When David Shannon passed away in his brother’s Toronto home on Feb 2, 2018, the pain of losing a friend, colleague and fellow journalist and activist was compounded by a strange bit of timing.

Shannon’s death came in the wake of criticism of the Toronto police, who had repeatedly been asked about the possibility that a series of murders in and around the city’s gay Village might have been connected. The police had said they had no evidence to suggest that the murders were connected, and dismissed the idea of a serial killer stalking the city’s LGBT citizens.

Then an arrest was made, and the alleged serial killer was all over national and international news.

The violence, the patterns, the warnings to police and their subsequent denials, had striking similarities to the rash of homophobic violence that Montreal’s queer community experienced in the ’80s and ’90s. And Shannon had been part of a group of activists that pressured Montreal police to take the crimes more seriously and consider that some of them may be connected — something that the police denied, but that later turned out to be true.

It was one part of the intelligent, informed activism that Shannon leaves as a legacy. In 1988, he began writing “Out in the City,” with his friend Don Rossiter, for the now-defunct Montreal Mirror. The following year, Shannon, who also hosted The Homo Show on McGill’s community radio station CKUT, would begin writing the column by himself, making it one of the first gay columns to appear in an alternative weekly newspaper in Montreal.

For many of us (I was an undergraduate student at Concordia University at the time), Shannon’s scrappy, bitchy, take-no-prisoners style left an indelible impression that even three decades ago, a number of people I’ve spoken to since his passing still fondly remember. One of these memorable columns was on Aug 4, 1989, when Shannon took aim at police for their announcement that they would be clamping down on park sex.

Special attention would be paid to Mount Royal Park, which Shannon noted was a favoured cruising ground for the city’s men who were having sex with other men. “It seems that with mounting violent crime in our streets and escalating domestic violence,” Shannon noted, “gay sex becomes an easy scapegoat.”

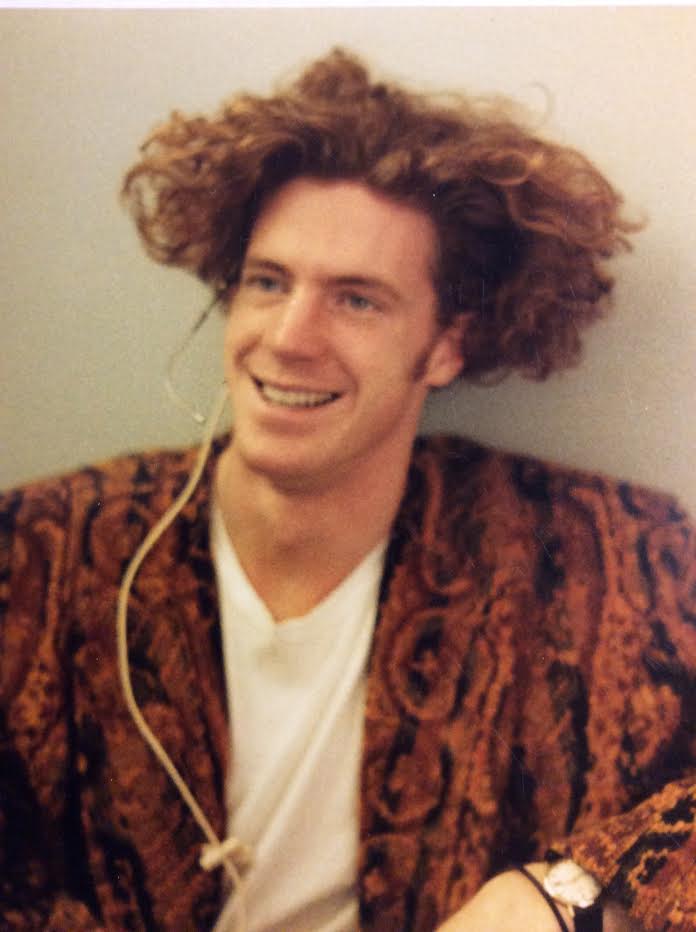

David Shannon in the late ’80s, when he was working the reception desk at Estetica, a Montreal hair salon. Credit: Courtesy MacRae Campbell

“David was committed to pointing out the shortcomings, especially in Quebec, where there was considerable pride about it being the first province or state in North America to have gay-rights legislation,” says Michael Hendricks, a Montreal-based activist who worked alongside Shannon for many years. “David noted that in terms of equality on many fronts, none of that promise was actually being upheld.”

After Montreal hosted the international AIDS conference in 1989, there was a push to start a local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), the radical activist group co-founded by Larry Kramer and Vito Russo in New York City. “David wrote about it in his column, so when he announced that there would be a meeting to organize, about a hundred people showed up,” Hendricks recalls. “The early success of ACT UP Montreal was as a direct result of David’s column and his considerable and loyal following.”

Shannon co-founded both the Montreal chapter of ACT UP and the AIDS Community Care Montreal (ACCM).

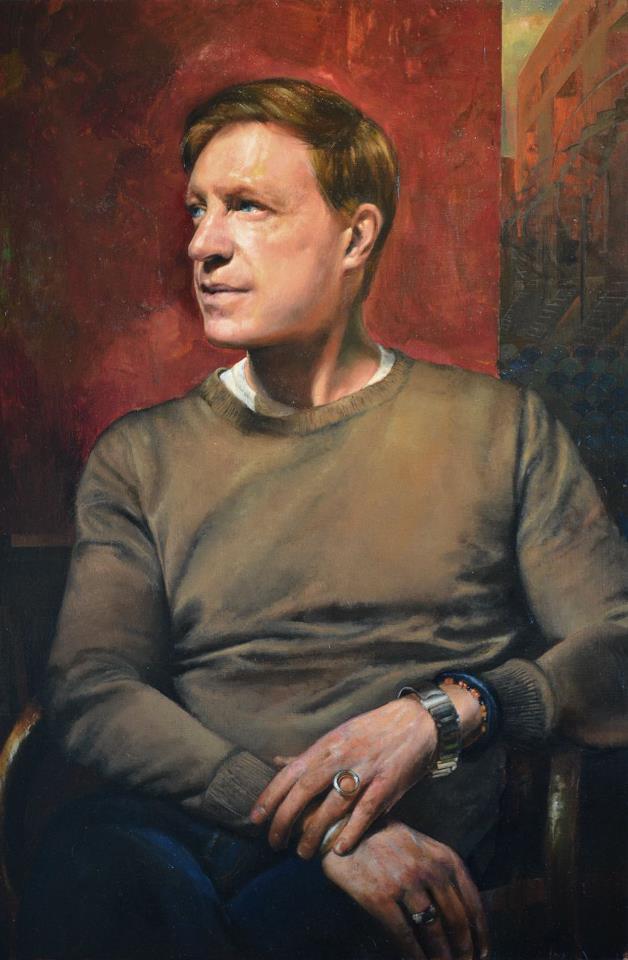

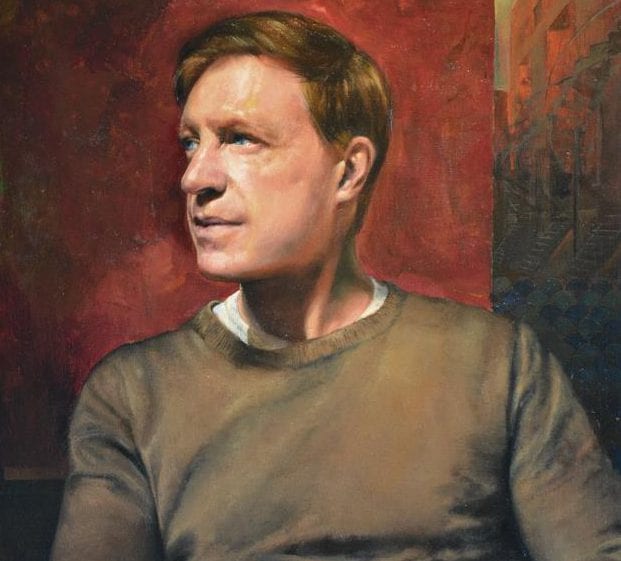

A portrait of David Shannon painted for his 50th birthday. Credit: Courtesy James Huctwith

As a result of the activism of Shannon and his fellow activists Hendricks, Elizabeth Neve, Roger Leclerc, Claudine Metcalf and the late Douglas Buckley-Couvrette, the Quebec Human Rights Commission launched an inquiry into homophobia in 1994. The committee, led by human rights activist Fo Niemi, heard testimony from hundreds of the province’s queer citizens, who urged for change in education, police relations and social services generally. Last week, Niemi posted on Facebook that Shannon would be remembered for his considerable contributions to the city’s gay community.

Shannon was a friend, a colleague, and someone who fought hard for the rights of everyone. Hendricks recalls that in a pre-internet era, Shannon’s column held an especially important place for Montreal’s queers to connect. “I read the column, as did pretty much everyone,” he says. “If you wanted to strike up a conversation with someone you knew, you just brought up the latest thing David had written. You could rest assured they had read it too.”

Despite his very vocal stance as an activist, Shannon was not very public about his own HIV status, though he discussed it with friends, and HIV clearly had a huge impact on his health, as he was forced to take disability leave several years ago from the CBC. He eventually succumbed to liver cancer.

I used to love bumping into David when I’d come to Toronto, usually at the Black Eagle, which was one of his favourite dives. I’ll miss his laugh, his sharp wit, and his brilliant commentary on politics, fashion, fine dining, all manner of current events, and knitting.

I’ll never forget the way he captivated crowds with his speeches, keen wit, and his striking red hair and piercing blue eyes. I remember when I was a grad student at Concordia University in the ’90s and a fellow student turned to me and whispered, “I think I have a crush on David Shannon.”

I responded, “Darling, so does the entire east coast.”

A celebration of David Shannon’s life will take place Thursday, Feb 15, 2018 at 7pm at the Tranzac Club.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra