You could call Alex Brett Ottawa’s lesbian Agatha Christie. But that wouldn’t be entirely fair. Unlike Christie’s lightweight books, Brett’s murder mysteries have a heavy twist of science for the masses. And that requires a dense writing style that forces the reader to pay attention lest they miss the details.

You learn something reading Brett’s mysteries. Her first novel, Dead Water Creek, gave you a virtual marine biology course in West Coast salmon. In Cold Dark Matter, you learn about astrophysics and about a nasty little piece of technology that ruined the lives of thousands of gay and lesbian civil servants. Canadian civil servants.

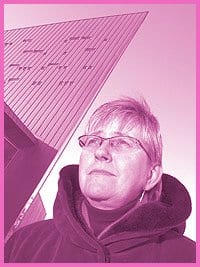

So when I meet Brett in a crowed coffee shop on a Sunday afternoon, I want to talk not only about her fictional detective, Morgan O’Brien, but about the intellectual weight of her books.

“What I say about my writing is that I take no prisoners,” Brett says. “My work is not going to appeal to everyone, but it does appeal to people who want that kind of mental challenge.”

Billed as probably the only mystery novel that unites gay literature fans and astrophysicists, Cold Dark Matter gives us a good murder with a healthy dose of science added to the mix. But it doesn’t stop there; the novel also probes some of the darker chapters of Ottawa’s Cold War past, most specifically the infamous attempt at building a homosexual detector, commonly known as the “Fruit Machine.”

So why did Brett write about the Fruit Machine? Actually, she explains at great length, the real-life story of the Fruit Machine was a key inspiration for the novel. She was disturbed by the way it had been treated as a joke by those in the know. Absent from the public discussion was an understanding of the suffering of people who lived through the period of official witch-hunts, political purges and police paranoia. The process of writing about it helped Brett to purge that ghost of the early 1960s.

“I’m no longer haunted by the Fruit Machine and the images of these people being affected by it,” she says.

Something she wasn’t prepared for was the realization that the excess of the Fruit Machine period, the official paranoia, is being repeated in the post-9/11 era. The Cold War mentality is refracted back at us today with the anti-terrorism act. What excesses lie ahead?

“The role of the fiction writer is to ask questions, not answer them,” Brett asserts. “And the role of the fiction writer is to ask how things affect people.”

Just how do you determine who the enemy is, she asks, and to whom do you give the power to make that determination? The paranoia was real then and it’s real now. In the Cold War, government gave that power to the RCMP, and they were unprepared to use it responsibly.

Brett is quick to point out that the depiction of the Fruit Machine in the novel is a fictionalized account, partially because of the scarcity of data available to her. It’s only now, with the book published, that more data is coming to her from her readers, including those who lived through the purges. Already dealing with heavy content on the science side of the novel, Brett decided to take the facts then available and play with them to suit the story. She emphasized questions about how the technology could be further misused by people with their own agendas.

But the novel, Brett insists, isn’t about the cold heart of paranoia or the icy matter of space research. It’s about how people, even characters in novels, escape the limits others try to put on them and insist on their own way forward.

“This isn’t a book about the Fruit Machine,” Brett says. “This isn’t a book about dark matter. It’s a book about a bunch of people, and what happens to them, and that supersedes everything else. It supersedes all factual information, this story of these human beings and how they got caught in it and how they coped with it.”

Part of the fun of the novel is following Morgan O’Brien as she moves through Ottawa’s eighbourhoods. Brett’s descriptions of a dark underground gay bar piqued my curiosity – it seemed so out of place in today’s Ottawa.

Brett laughs when I bring this up.

“I came out in the late ’70s/ early ’80s, and those were the bars I went to in Vancouver.” While she admits that the depiction is generational, it also serves to convey the post-Cold War mentality that echoes through the novel. “That’s the mind of the writer – you are in a dark world, so you envision everything as dark.”

In fact, readers of her first book might have a bone to pick with Brett. Hero O’Brien’s sexual ambiguity in the first novel appears transformed into something more decidedly heterosexual this time round. Brett laughs it off with a comment about “shades of grey” and adds that she wouldn’t place her bets on Morgan being on one side of the fence or the other.

COLD DARK MATTER.

Alex Brett.

The Dundurn Group. 2005.

$11.95.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra