"The closet was a convenient, or a necessary, strategy that had the effect of protecting us," says James Loney. Credit: Nevena Todorovic

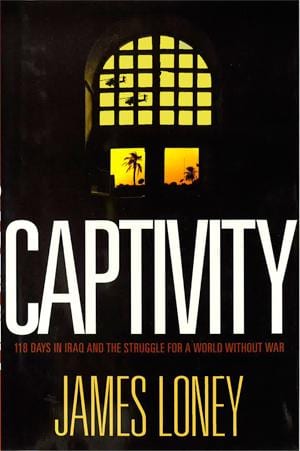

“It is a paradox,” James Loney writes, not more than a page into his book Captivity: 118 Days in Iraq and the Struggle for a World Without War. The book is a detailed account of being kidnapped in 2005 by an Iraqi resistance group and later rescued by American and British military personnel.

“My freedom comes directly from the hand of the soldier… Yet I remain a pacifist,” he says.

Apparent paradoxes are nothing new to Loney, who was snatched early in his mission with the non-violent activist group Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT). A Toronto resident since 1993, Loney is a thoughtful, socially conscious gay man. He is also a Catholic whose politic is largely informed by his faith.

“It was a profound tension. I’ve always had, since I can remember, some sense of the presence of God in my life, but I also felt this profound feeling of not being what I was supposed to be,” he tells Xtra. “I was taught that homosexuality is the worst possible thing. Through a process of study and reading, I saw that there are other theological points of view that open up that, in fact, queer people are part of the biblical story, that the gospel is about love.”

“Religion has and continues to be used as a tool of the oppressor to maintain oppression,” he continues. “That’s actually contrary to its true purpose or what it actually is, which is for the liberation of every human being.”

If reconciling his sexual identity with his faith proved somewhat difficult, the decision to hide his gayness from his captors was not. While in captivity, the international media, governments and Loney himself kept his sexuality and his then-partner’s identity a secret on the understanding that if his captors knew he was gay, it might be an incentive to harm him.

“The closet was a convenient, or a necessary, strategy that had the effect of protecting us,” he explains.

Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty presented Loney with the Pride Toronto Fearless Award in 2006, but Loney returned it in 2010 to protest Pride Toronto’s decision to bar Queers Against Israeli Apartheid from the parade.

Loney is careful to point out that his sense of homophobia is not one in which Iraqis are merely bigoted; rather, he sees all aspects of oppression as variously interlocking.

“Homophobia is a continuum,” he says. “Whether it’s the high school bullying taunt here, it’s the same essential dynamic as, let’s say, Iran, where they are hanging young men who have sex with men. It has to be understood that way,” he insists.

“In a way I knew a lot about our captors, and in a way I knew very little. The context of Iraq that was created by invasion and occupation put a society to shock; people targeted people who were the other,” he explains. “In that context it was just better not to introduce that to our captivity.”

So the paradoxes complicate: the unwarranted US occupation of a Middle Eastern country that, under the dictator Saddam Hussein, had discreetly tolerated a gay society, has the unintended effect of then endangering queer Iraqis. And as violent, fundamentalist Islamist groups proliferate in reaction to Western hostilities, the need for peace activists like Loney becomes more severe. The context of invasion, which Loney sought to dismantle in Iraq, thus reimposes the closet on him as a peaceful defence mechanism.

As dense as the politics of his story are, Loney’s queerness is actually not much of a topic in his book. He once mentions being anxious about its discovery to Norman, one of the other three CPT hostages. Besides that, some mention of his then-partner, Dan, a few dodged questions regarding his marriage status, and vaguely homoerotic massage sessions with one of his captors, the issue goes without much remark.

More striking about the book are the intersecting developments of Loney’s pacifism and his experiences in captivity. The episodic explanations of his personal philosophy around conflict come to illuminate the slow and gruelling details of his experiences.

“My biggest worry was, ‘Can I convey this story in an interesting way?’” he says. “Captivity fundamentally was an experience of excruciating boredom.”

There is, then, even another seeming contradiction: Loney’s time as a hostage was total monotony. In its retelling, though, it is a captivating, multidimensional and self-complicating narrative of activism, religion and violence: far from boring.

Regarding the paradox of his rescue, Loney can offer only Captivity to explain it.

“I feel that [my] story is the answer to the paradox,” he submits. “The paradox involves seeing through the lens of this story.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra