Canada Customs has long exercised much more coercive control over the reading pleasures of Canadian queers than any police force. Obscenity charges by the police are rare these days. One of the reasons is that obscenity trials are public.

Bureaucracies like Canada Customs, by contrast, work behind closed doors. Despite customer-service-type rhetoric, officers are accountable only to their managers. And Customs managers are wasting taxpayers’ money by directing employees to search shipments of books destined for gay and lesbian bookstores, and to seize them if anything seems, “degrading and dehumanizing.” That’s one of the definitions of obscenity under the department’s guiding 9-1-1 memo.

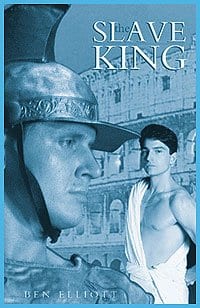

As we’ve seen in the case of the books Cherry and The Slave King, seized by Customs this summer, gay and lesbian erotic books that make it to regular bookshops have a habit of not turning up for their most eager customers. Customs communications officer Colette Gentes-Hawn told Xtra this fall that what looks like sexual targetting is actually that marvel of modern management: risk. “We look at the level of risk since we obviously can’t look at it all,” she said.

How is the level of risk determined? Obviously, since gay and lesbian bookstores have been in trouble with Customs before, they are high risk. So their shipments get examined closely, while shipments to other stores get waved through.

Sound like racial profiling? It is. That too is justified by police officers as a risk management tool. Police know for a fact young black males have in the past been in trouble with the cops. So they stop them more often. That then generates more data to justify the initial profiling.

The self-fulfilling logic of profiling adds a scientific, modernizing flavour to discrimination.

Risk management is not the only modernizing move made when Customs revised its infamous “categories of obscenity” in memorandum 9-1-1. Invoking modernity and “community standards” (not the gay community’s, of course), they seem to believe that because the total ban on anal penetration that used to be there has now been eliminated, we’ve arrived in equality heaven.

The Supreme Court Of Canada chastised Canada Customs for their homophobic and generally ignorant censorship practices back in the 1999 Little Sister’s case. The court suggested officers need better training. But how could one possibly train officers to fairly and rationally target publications to be seized? I’ve been a court-certified expert in “the sociology of sexuality” on occasion, but even I would throw up my hands in despair if asked to devise the training the Supreme Court recommended.

The problem does not lie in any one of the categories of obscenity listed in the memorandum. The problem lies in the idea – which comes from criminal obscenity statutes and judicial decisions – that ethical distinctions regarding publications and films can be made by rhyming off a list of bodily acts.

Any woman knows that there is a huge ethical distinction between, on one hand, a film of sexual assault that is meant to arouse the viewer and glorify rape, and, on the other hand, a film of sexual assault produced perhaps by a victim, feminist artist or just a good filmmaker.

A couple of years ago, at a meeting of the editorial collective of the US journal Feminist Studies, we were looking at a series of disturbing drawings showing a girl being sexually assaulted by a man. They were very explicit. We knew they had been sent to us by a survivor, who wrote complaining that her work was constantly rejected as unsuitable for feminist art outlets. She felt that she and other survivors ought to be not only allowed but encouraged to depict their experiences as graphically as they wish.

This situation points out that the problem with governing sexual representations by means of lists of sexual acts lies much deeper than in the use of vague categories in 9-1-1, such as “sex with exploitation.”

So I think it’s important for queers not to get drawn into a discussion about how to improve this list. Instead, we need to question not just this or that list, but the assumptions about sex and its relation with ethical issues. It is not what is done or what is shown that matters. What matters is how it is shown, in what context and for what purpose.

Bureaucracies are inherently unable to deal with context. Bureaucracies have to stick to risk classifications (drawn from their own discriminatory past practices) and to standard forms with boxes to be checked off. So bureaucracies can never govern sexual representations in anything resembling a rational manner.

So why not pressure MPs to tell Customs to just lay off books and films? After all, even those of us who have some concerns about extreme pornography know perfectly well that you can get much worse home-made stuff off the Internet than in the publishing or film industries. I don’t see any good reason for continuing to have Customs officers even look at books and films.

Cops using the Criminal Code are no more enlightened, but at least their actions are subject to public scrutiny in the courtroom. And cops can only lay charges after the fact; they can’t pre-emptively seize books that nobody in Canada, including the importer, has even opened. Cops also can’t impose extralegal financial penalties on our cultural institutions, something which Customs has been doing for decades.

The only rational Customs policy on obscene importations is no policy.

* Mariana Valverde is with the criminology department of the University Of Toronto.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra