My decision to move to the suburbs was whimsical. On short notice and during an unsuccessful apartment hunt, a relative of mine said she had a spare room in her new house — in Kanata.

Cheap, cheap rent. A short commute downtown to where I work and play. Very close to the park-and-ride (which sounds like a more exciting place than it actually is, by the way). That’s the mental arithmetic I did when carless, and looking back, careless, I made Kanata my new home.

Four painful months later, I find myself living downtown again. With the move comes the realization that my place should be smack in the middle of everything. Not that I didn’t enjoy my 20 minute trots to Food Basics, or the two-kilometre excursions from where I lived to Starbucks.

I could handle my fellow passengers of bus route 96, going to and from, and to and from work. I sometimes brought my iPod; then, I joined in a game of Ignore your Neighbour. If you make eye contact, you lose.

No, it was more than that. At the age of 26 and at this point in my life, I realized that suburbs were simply not my bag. Now, I live in the centre of the city — in the Rainbow Village.

The condos are coming

In the core of downtown Ottawa lies the Rainbow Village, the place I now call home. A giant leap from Kanata, I love being close to everything, walking everywhere and absorbing everything the city offers. Gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transfolk seek housing downtown because, whether founded or not, there is a sense that downtown neighbourhoods tend to be more accepting of sexual diversity than suburbs. And if you’ve walked the streets of Ottawa recently, you may have noticed a number of things that seem to be sprouting up everywhere, and it’s not even tulip season yet.

Condos are sprouting up in downtown Ottawa — and many other North American cities. Condo residents own, and pay a monthly fee, for a space that blends the benefits of a house (accruing equity, riding rising housing prices) and an apartment (convenience, low maintenance.)

Brian Ray, geography professor at the University of Ottawa, says that in many Canadian cities, home ownership in the downtown core is increasing, largely due to the influx of condos. Vancouver is a prime example.

“The increase in home ownership in Vancouver is so common because of immigration and because it’s such a beautiful setting. You can get up, look at English Bay, look at the mountains — it’s a spectacular spot.”

But the influx of condos has not had the same effect in Ottawa, Ray reflects, gazing out his own condo window. The view? A gas station, a church under renovation, and the best eye candy of all — a parking lot. Ray lives in Centretown, and his not-so-picturesque view is not uncommon to the area.

“If you walk around downtown Ottawa, on Metcalfe or O’Connor for example, and count the number of parking lots, the number of abandoned buildings, there is so much space that could be used for housing development,” he says. “You’ll see how much empty land there is here — you just would not see this in Vancouver.”

What’s the holdup?

David Gladstone has lived in Ottawa city for 21 years. Gladstone attended a meeting last week regarding a proposal from Claridge. The developer proposed that Ottawa should house Canada’s Portrait Gallery on Metcalfe St. The site is currently a parking lot; the proposal is for a 27-story building. The first two storeys of the building would house the Gallery, and the remaining stories are planned for condos.

Across from the proposed site is a low-rise block of buildings in the Centretown heritage conservation district. Gladstone was among the meeting’s participants who does not want the Gallery in Centretown.

“It would not be very pretty,” he says, “and there are plenty other places for it to go. Why don’t they put it where originally planned — in the old US Embassy?”

As I spoke with Gladstone, he was on his cellular phone and walking through the Golden Triangle. Despite the recent proposals, he says that developers generally try to stay out of Centretown.

“They choose their battles carefully,” he says. Gladstone would rather see the “monster buildings” in the central business district, but height limitations are in place there because of the Peace Tower.

Gladstone says that many property owners in Centretown are hanging on to old buildings and parking lots because they are waiting for the city to let go of zoning restrictions such as density limits, and for property values to skyrocket.

Gladstone does not believe that the density in Centretown needs to increase.

“Centretown is dense enough as is,” he says. “We need to keep the residential area residential, and the businesses on Bank and Elgin.”

But the population density of Ottawa is extremely low when compared with other cities in Canada. The density of Ottawa is only 292 people per square kilometre, compared to Vancouver’s downtown density of 5,039 and Toronto’s 3,972.

In fact, urban density in Ottawa has been on the decline since 1925. At the time, there were 57 people per hectare, compared with about 28 people per hectare today, according to the City of Ottawa.

In Feb, The Ottawa Citizen put the problem graphically. A piece entitled “Ottawa’s Big Problem” included a frightening map that showed the amalgamated city of Ottawa overlaid with outlines of Vancouver, Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton and Calgary. These five major cities (although not their metro-census areas) fit inside Ottawa’s boundaries. Measuring a total land area of 2758 km2, Ottawa is big.

Cities can increase their densities in the urban cores in a number of ways; one way is to increase the number of residential high-rises. But many cities, including Ottawa, height limitations constrict development.

How high can you go?

The City of Montreal recently imposed height restrictions for real estate surrounding Mount Royal, to ensure the beautiful mountain will continue to be seen from many angles throughout the city. In Orlando, Florida, waterfront condo-owners fight for condo height limits to make sure their beaches stay shadowless. Ottawa is no exception in its desire to keep building heights low.

Measuring in at 92.2 metres, the Peace Tower overlooked all buildings in Ottawa until the 1970s. Originally, no building was to be built higher than the Peace Tower, so it could be seen from anywhere in the city. Some buildings in Ottawa now exceed the height of the Tower, but not without opposition. There is a suspicion that high-rise buildings will negatively affect aesthetics and property values of surrounding areas.

Diane Holmes is the city councillor for Somerset Ward in Ottawa, which encompasses the Rainbow Village. Height restrictions for a given building vary depending on the part of town, she says. North of Gloucester St and in the central business district of Ottawa, the height limit is 22 stories. South of Gloucester, there is a 12-story limit. South of Somerset, building height is limited to three stories.

The point, Holmes says, is to “decrease the height of buildings as you move from the business district to the residential district.”

Ensuring that buildings meet zoning requirements is a key issue of the Centretown Citizens’ Community Association (CCCA). They lobby to keep long-standing building height limits are respected.

As a consequence of the CCCA’s opposition to high-density buildings, projects for buildings that do not meet zoning requirements are sometimes abandoned, leaving rotting buildings or parking lots to dot the landscape.

It’s ironic, because the CCCA also opposed highway construction downtown. If you oppose both highways to the suburbs and development downtown, where are people who work downtown supposed to live?

However, Holmes emphasizes the importance of people having sunlight entering their units, and that very high buildings can “create an overwhelming canyon effect from a pedestrian perspective.”

High buildings can prevent sunlight from reaching the sidewalk and create narrow wind tunnels. Her ward has the smallest amount of green space of anywhere in the city, says Holmes, and at the same time absorbs a large amount of intensification and increases in numbers.

“You have to balance the transportation pressure, the sewage and water systems, the parking pressure, the desire to have more people living here to keep it exciting, and maintain a strong sense of community and business community too,” says Holmes.

“The balancing act has been very successful up until now,” adds Holmes, who’s represented the ward since 1982. “I think we have a good mix of different heights as they step toward residential areas in the southern part of downtown.”

Zoning bylaws in Victoria have shown flexibility in building height restrictions. A deal was struck whereby condo developers agreed to support the refurbishing of the historical Hudson Bay Company building. In turn, developers have been given permission to build condos several stories higher than the bylaw would normally allow.

But obviously condo developers need to make a profit. Ray says that in order to do so, properties will often be developed lot line to lot line, come right up to the sidewalk and some developers prefer the practical to the beautiful. But with height restrictions, we end up with the worst of both worlds.

“We end up having smaller buildings that are more ugly and don’t meet the sidewalk creatively. There are many non-attractive buildings in Ottawa.”

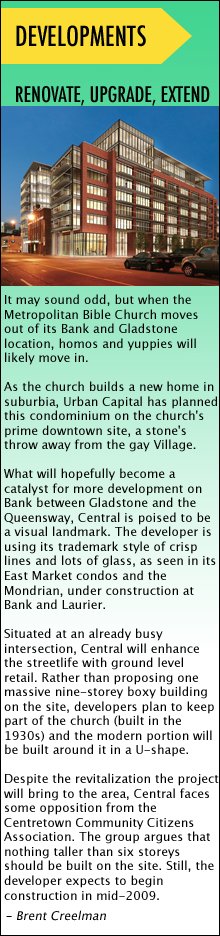

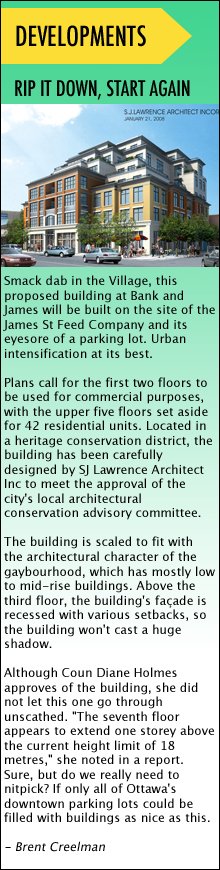

There has been some headway recently. In February, the city’s planning committee approved a new mixed-use building planned at James and Bank (see sidebar).

Several of the building’s characteristics, including height, did not comply with the zoning limits for that area of Bank St. The building will have underground parking and is intended to have a “distinctive architectural presence,” according to the report. Upper floors of the building will be set back from the primary façade. The first two floors will be commercial and the top five residential. It shows that creative solutions are possible.

However, a recent plan for the development of a six-storey condo in New Edinburgh is receiving significant resistance from the New Edinburgh Community Alliance. The Alliance is concerned that such a large building would change the appearance of the street, located in a Heritage Conservation District. Such developments offer great potential for building density downtown, but for the time being Ottawa remains a city where urban sprawl is the norm.

The penalty for not developing

Ottawa remains a poster child for old-fashioned urban development. As was the trend post-World War II, everything new is being built on the periphery of the city, and there is a reluctance to change.

Losing people from the urban core means losing services and shopping. The result? Less people on the street. And the lack of people out on the street is not due to the cold weather, it’s due to lower urban density.

Without pedestrian traffic, street-level shops tend to close early — or they go out of business altogether.

As the city spirals outward, transportation costs go up. With gas prices soaring both drivers and transit planners feel the pinch.

“Having fewer people on the street makes Ottawa a less interesting place to walk through. But both developers and politicians are trying to provide peripheral housing. They are not trying think about building the city in different ways,” says Ray. “And the same is true for Gatineau — it is a continuous suburban sprawl.”

As well, the environmental costs of suburban sprawl are well documented. As development spreads, ecosystems are disrupted and watersystems tainted. And the environmental damage caused by heating single-dwelling homes is far larger than that caused by heating apartments. Not only does urban sprawl detract from the vibrancy that could be Ottawa, but it causes higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions due to increases in transportation. High traffic levels produce smog and affect air quality.

The CBC reported in 2006 that in Ottawa Centre, renters outnumber homeowners almost two to one. Buying a house downtown is usually very expensive and requires extensive renovations.

“If you can save $100,000 by buying a house that fits your needs on the periphery of the city, then people do that.”

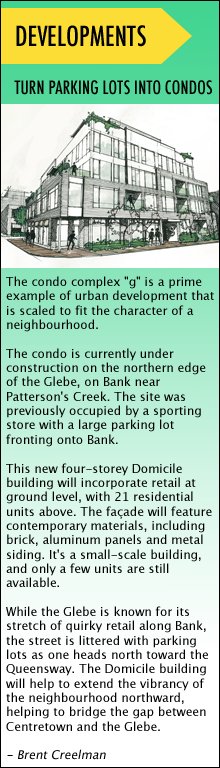

The solution is a proliferation of condos, but until zoning restrictions are relaxed, downtown Ottawa is going to continue to be pock-marked with empty lots.

The cost of buying in downtown Ottawa is less than cities like Toronto and Vancouver, but property taxes can seriously increase the cost. Especially with the expiring provincial tax freeze, which will affect core urban neighbourhoods in Ottawa the most. The average yearly income for Ottawa families living downtown was $84,956 in 2006, according to CBC.

The city’s Official Plan claims to prevent suburban sprawl. Ottawa, it says, has “recognized concerns with urban sprawl and has adopted a policy of not expanding urban area boundaries.”

But that plan seems contrary to Ottawa’s zoning restriction policies, and the result has been a booming housing construction market across the river.

As a city spreads, there is less and less natural landscape. Commuting consumes more time of the day, affecting quality of life. And alas, we come full circle to the reason why Ottawa commuters are the happiest people I know.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra