“What was the feeling like of being in Ohio? It was like being in a pressure cooker,” says Laurel Powell, the former director of media relations for Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio. “I felt like we were kind of one of the last lines of defence before it all started to go apart.”

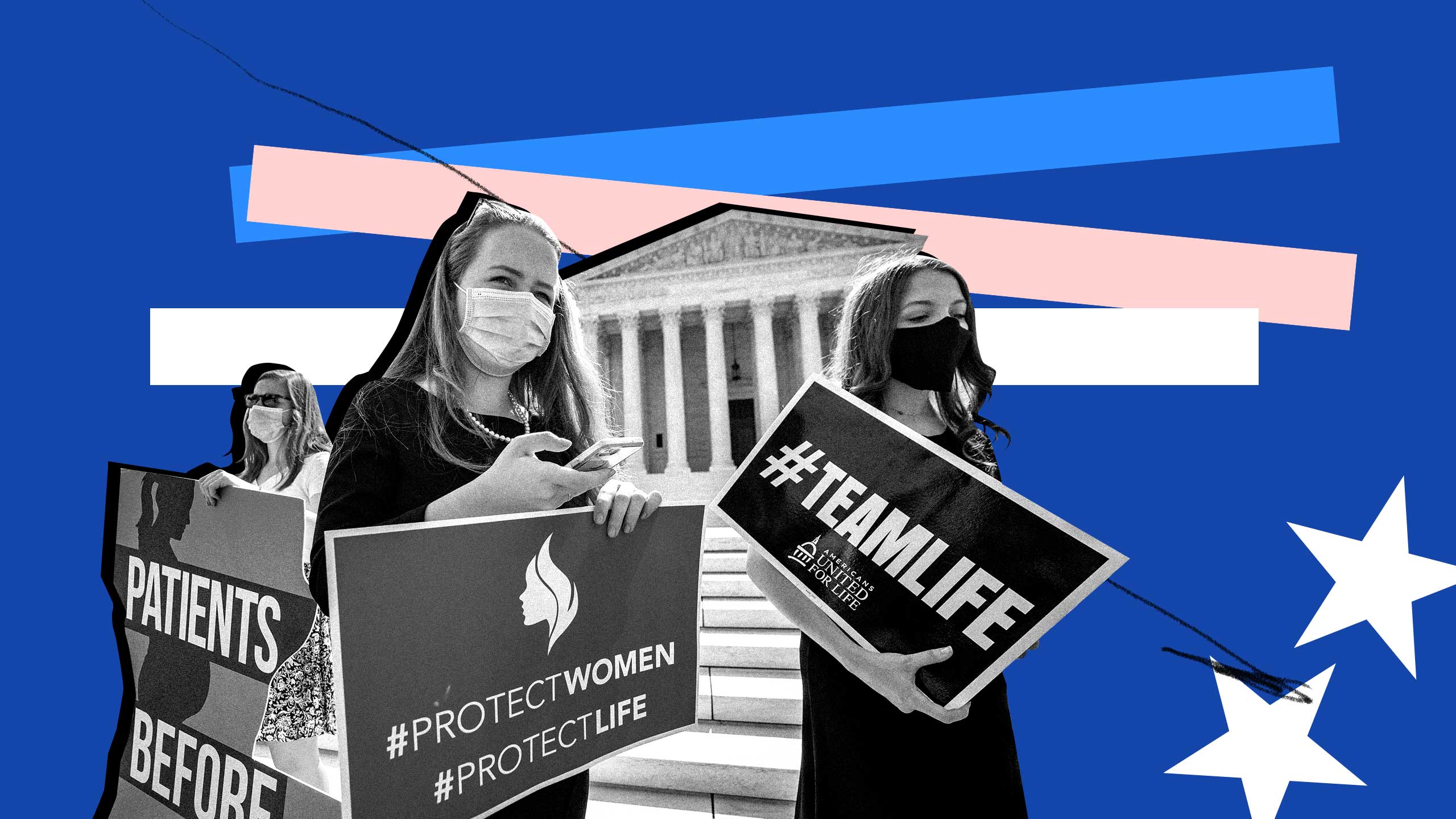

Powell, who now lives in Washington, D.C., spoke to me in her personal capacity. Her story, though, made it clear why the job had been terrifying. As the “the openly trans spokesperson for a red state abortion provider throughout most of the pandemic,” Powell regularly dealt with crises like violent and enraged anti-abortion protesters forcing their way into clinics. She very much doubts that violence will dissipate if and when abortion becomes illegal across the U.S.

“Unfortunately, I kind of see the future of the anti-trans movement in a lot of what the anti-abortion movement is doing,” Powell says. “We’re now at a moment where Roe v. Wade is very much imperiled, if it isn’t already dead in the water. I fear that some of that energy and some of those tactics are going to be turned more toward trans people specifically. [These protesters] are angry. They’re fired up by misinformation, by bias on social media, by far-right figures, and they’re going to want to put that energy somewhere.”

If the current state of anti-trans protests is anything to go by, Powell is right. Recent weeks have seen reports of anti-trans protesters collecting addresses of clinics that provide gender-affirming health care, gathering outside trans health care clinics to harass people and conducting “stings” on providers by posing as parents seeking treatment for minors. Those tactics have all been used in the past by anti-abortion protesters—and they have also, historically, led to clinics being bombed and doctors being assassinated.

Elliott Kozuch, the D.C.-based senior communications strategist of NARAL Pro-Choice America, says that there’s precedent for this kind of shift. They trace the strategy back to a long line of American anti-identity politicking, and ultimately, to white supremacy and the end of the school segregation movement.

“As the anti-choice movement is focusing on abortion and attacking it at every turn, they’re realizing that LGBTQ issues are almost an extension.”

“As the radical right forces started to lose public opinion on [segregation], they had—and this is documented—meetings to see what the shift should be, how to continue to have the vote, the numbers they had, without being able to use school segregation, which had become a losing issue for their side,” Kozuch tells me in an email.

“In those conversations, abortion emerged as the successor,” they write. “I think now we’re seeing that as the anti-choice movement [is] focusing on abortion and reproductive freedom and attacking it at every turn, they’re realizing that LGBTQ issues are almost an extension.”

Such tactical shifts can confound the opposition, in part because the left tends to be decentralized (not to say disorganized) with many competing priorities and causes, whereas the right’s tendency toward authoritarian leadership and top-down strategies allow for a more co-ordinated attack. While reproductive rights and queer liberation movements squabble, their enemies come in and clean up.

Ohio—where Powell worked and where I grew up—is proof of how fast this can happen. As recently as the 2000s, it was a moderate swing state. In less than a decade, thanks to some clever gerrymandering, it became the stage for some of the most restrictive anti-abortion laws in the country. Now, with Roe likely on its last legs, Ohio has introduced a raft of punitive bills targeting trans kids.

Which brings us to the Handmaids. Anti-trans organizers and TERFs have been actively working to heighten the tensions within the anti-abortion movement. The right explodes into manufactured outrage over language like “pregnant people” or “person with a cervix,” and second-wave feminists who would surely consider themselves pro-abortion—like, say, Margaret Atwood, whose 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale has become a go-to allegory for abortion protesters—fret that trans-inclusive abortion politics might constitute female erasure. Trans liberation is framed as a threat to cis women’s reproductive and bodily autonomy.

“Banning trans people from public life and banning abortion are all about installing a regime of gender roles.”

Yet anti-trans organizers are hardly bold advocates for choice. U.K. hubs like Mumsnet increasingly frame pregnancy and motherhood as the central defining fact of womanhood—one that’s in need of protection from the queer hordes. In her recent writing, author J.K. Rowling throws in digs at abortion as well as trans women. Take a step back, and it seems clear that anti-trans forces are converging with the right wing in a decades-long project of rolling back the sexual revolution: to be a woman is to give birth, and to give birth is to be a woman, no exceptions.

“Opposing childcare, banning queer identities, banning trans people from public life and banning abortion are all about installing a regime of gender roles that is functionally based on ‘Biblical manhood’ and ‘Biblical womanhood,’” says D.C.-based Gillian Branstetter, press secretary of the National Women’s Law Center. “I don’t think state legislators that are ranting about puberty blockers are thinking about it like that.

“But the people writing these laws, the people lobbying for these laws, the organizations who are inviting Supreme Court justices to conventions and who are training armies of lawyers to argue against these things in court, I think their explicit goal is to install extremely strict understandings of Biblical manhood and Biblical womanhood into the law.”

That project goes far beyond the borders of the United States. Branstetter points to the fact that homophobic legislation drafted by U.S.-based hate groups like the World Congress for Families can end up in places like Ghana. Ultimately, as Judith Butler has pointed out, anti-trans organizers’ emphasis on restoring traditional, biologically essentialist gender roles puts them in alignment not just with the Christian Right, but with global fascism: “The anti-gender movement supports ever strengthening forms of authoritarianism,” writes Butler for the Guardian. “Its tactics encourage state powers to intervene in university programs, to censor art and television programming, to forbid trans people their legal rights, to ban LGBTQI people from public spaces, to undermine reproductive freedom and the struggle against violence directed at women, children, and LGBTQI people.”

Pushing for a return to the heteronormative “family”—both by depriving people of reproductive freedom and by punishing queer gender expression—is a recognizable tactic of right-wing populism the world over, Branstetter says: “It’s what’s happening in Hungary, it’s what’s happening in Poland, it’s what’s been happening in Russia for the past 30 years. It’s in some ways what’s happening in the U.K., what mobilizes the far right in France, in Greece, in Germany. It’s what’s happening in Brazil under Bolsonaro.”

“There is a conceivable future in which both reproductive and queer justice movements effectively co-ordinate to fight a mutual enemy.”

It’s important to note that reproductive justice and queer movements are not universally at odds. Every advocate I spoke to stressed that grassroots and Black-led reproductive justice movements like All* Above All and Sister Song have been doing queer-inclusive work from the very beginning. Yet the mainstream abortion movement—largely built during feminism’s second wave, with its rhetoric (still) centred on relatively privileged white, cis women—is still catching up.

That knowledge gap can be stressful for trans people working in reproductive rights. “To say that I am tokenized would be a gross understatement,” said one person, who agreed to be interviewed under conditions of anonymity. They told me that even when transphobia wasn’t directed at them, they had witnessed coworkers misgendering trans colleagues, intentionally using the wrong pronouns for colleagues they disliked and “[painting] every single trans person of colour as ‘difficult to work with.’

“They want to use our voices to elevate their platform and seem inclusive,” the anonymous worker said, “but that doesn’t actually mean anyone is listening.”

The U.S., with its simultaneous attacks on both reproductive and LGBTQ2S+ fronts, is not unique. But the country is a test case for how bad things can get and how fast they can get there. There is a conceivable future in which both reproductive and queer justice movements effectively co-ordinate and exchange tactics to fight a mutual enemy—for instance, as journalist Katelyn Burns has suggested, adopting the long-standing pro-choice practice of clinic escorts for trans people trying to get past an angry mob on their way to the doctor. There is another, perhaps more likely, future in which anti-trans groups effectively sow division and resentment, and both movements fall into disarray.

Thinking back to her time on the front lines, Powell reiterates that feeling of being in a pressure cooker. The metaphor, she says, comes back to her often: “When you put things under pressure, fault lines that already exist are likely to pop open.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra