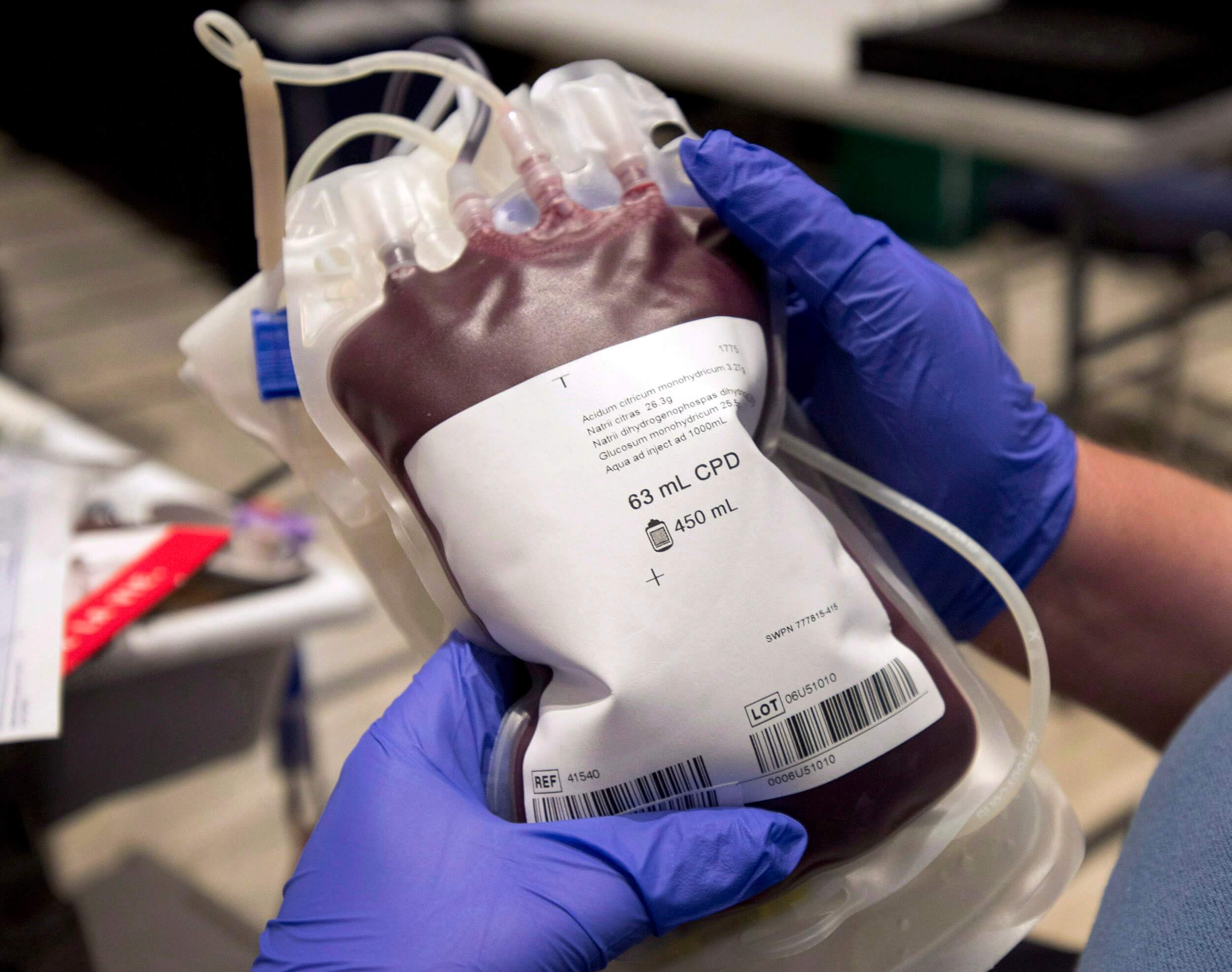

The American Red Cross declared its first-ever national blood crisis Tuesday, as the U.S. faces the worst blood shortage in over a decade due to the pandemic and staffing shortages. In light of the crisis, LGBTQ2S+ advocates are hoping that new research will lead the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to update the current rules around blood donations from gay and bisexual men, which they say are outdated and stigmatizing.

Researchers and advocates have been working with financial support from the FDA to pilot an ongoing study that they hope will lead to the elimination of discriminatory restrictions on donations from men who have sex with men (MSM). Their goal is to replace the outright ban with a risk-assessment protocol to screen people of any gender or sexual orientation who may be at higher risk of HIV.

“Identity-based or demographic-based discrimination policies are really not evidence based at this point,” Christian Morris, community engagement specialist at Whitman-Walker Health, who are partners on the ADVANCE study, tells Xtra. “It’s outdated, and there is a social stigmatizing element to it as well.”

The risk-assessment survey would evaluate factors like frequency of unprotected sex, frequency of partners and intravenous drug use. The ADVANCE study (which stands for Assessing Donor Variability And New Concepts in Eligibility) aims to survey more than 2,000 queer men to determine the survey’s efficacy.

A change like this probably wouldn’t solve the blood crisis entirely, but it would certainly help. LGBTQ2S+ advocacy organizations, including the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) and GLAAD, have urged the FDA to take action and change the criteria to help rectify the shortage.

In a statement, Joni Madison, interim HRC president, called the policy “discriminatory.” “The current policy is outdated, does not reflect the state of the science and continues to unfairly stigmatize one segment of society,” Madison adds.

Rich Ferraro, chief communications officer at GLAAD, also points out the ban’s unscientific basis. “All blood donations, regardless of sexual orientation, are screened to ensure healthy samples, and the American Medical Association, the Red Cross, leading elected officials and many others within the medical community have all called for the ban to be lifted,” he tells Xtra in a statement. “By relying on stigma rather than science, the FDA is not just harming members of the LGBTQ community, but all Americans.”

Lawmakers in the Democratic contingent of the Congressional Oversight Committee, including House Reps. Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), also urged the FDA to loosen the donation requirements in a Thursday letter to acting commissioner Janet Woodcock. They called the policy “troubling” and said it “continues to stigmatize gay and bisexual men and undermine crucial efforts to ensure an adequate and stable national blood supply.

“With the addition of an individualized risk-based assessment, the deferral period for all donors in the United States—including MSM—could potentially be eliminated,” the lawmakers write, pointing out that other countries including England, Scotland and Wales have done this in recent years.

The FDA’s current policy around blood donation, which must be followed by any U.S. organization that collects blood, states that in order to donate, a man cannot have had sex with another man within the past three months. Up until 2020, the deferral period was one year, but in April 2020, thanks to a drastic drop in blood supply due to the rise of COVID-19, this limit was temporarily decreased to just three months for the duration of the pandemic.

The one-year deferral period is also a fairly recent change. Until 2015, gay and bisexual men faced a lifetime ban from donating blood, which was enacted in 1983 as an early response to the AIDS epidemic. Despite significant scientific advancements in HIV treatment and testing since then, the ban’s legacy remains.

Currently, blood donations by people on PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), a daily medication that reduces the risk of getting HIV by 99 percent, are also screened out. Researchers hope that the study will help eliminate this restriction as well. “They assume it’s treatment for an active HIV infection, or they assume that people who are on PrEP are at higher risk for HIV,” Morris says.

The researchers behind the ADVANCE study aim to challenge this perception. While changing the parameters of who is allowed to donate probably wouldn’t completely solve the current blood shortage, the hope is to take a more scientific and less stigmatizing approach to the donation process.

In the coming months, researchers are hoping to recruit at least 2,000 participants across various locations throughout the U.S., which include the Bay Area, Washington D.C. and New Orleans. Those interested can learn more at advancestudy.org.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra