In the summer of 1983, an Ottawa actor named Peter Evans returns home from a period in England. He soon comes out as a Person Living With AIDS. He is the first gay man, the first person in Ottawa, to do so.

By then AIDS is two years old in North America. On July 3, 1981, the New York Times trumpets the arrival of Gay Cancer in 41 men. Someone tacks up the story at the Gays Of Ottawa Centre. Doctors are calling it GRID — Gay-Related Immunodeficiency Disease. Imagine the knotted stomachs of people as they read that article. It isn’t long before calls start coming in to the Gayline as people ask for more information. There isn’t any.

But by 1982, the first cases of AIDS emerge in Canada among haemophiliacs and people who have had blood transfusions. In March 1983, the AIDS Committee of Toronto is formed by gay men in that city, followed by AIDS Vancouver, but it will be July 9, 1985, well after Peter Evans dies, before Ottawa has one.

But right from the beginning, gay men are impacting on the official approach to AIDS. Some of our best activists switch from fighting gay-rights and sexual freedom issues to responding to this health crisis. They insist that gays sit across from scientists and bureaucrats on powerful committees. They ensure that the nation’s response to the virus does not roll out as an opportunity to use science and medicine to further oppress gays and lesbians, or control our sexual choices.

A couple of early battles involve defining safe sex and keeping bathhouses open. Unlike in the US, oral sex is labelled a low-risk activity in Canada, thereby giving gays an opportunity to “get wet” without participating in higher-risk unprotected anal sex.

Throughout the US, bathhouses are closed because health authorities, and even some misguided gay leaders, see them as sites for transmission. In Canada, in contrast, gay men win the day in their argument that bathhouses, and parks and bars, present ideal opportunities to hand out condoms and educate about safer sex. Closing the tubs, they correctly argue, would drive gay sex underground and make it harder to make progress on condom use. In the US, this is exactly what happens.

***

Our community’s response to AIDS is a lesson in the power of people working together. It’s an example of how individuals in a community under siege can prevail when we hold hands and push back against our fears, against a system loaded against us, and against an uncertain future. For that is the story of our response to the AIDS crisis. And it’s the story of our successes against other challenges to health, happiness, progress — and, yes, survival.

From the AIDS crisis that created a medical holocaust among Canada’s gay men, we learned to challenge the scientific, pharmacological, governmental and other powerful systems, and with success.

People still among us, and others who didn’t live long enough to see their history recounted, reshaped those systems and ultimately created a patient-centred response — a model for the entire medical system. For the first time in medical history, the patients insisted on being in charge of how their disease was treated and administered. And their successes serve us not only as a lesson in history, but an inspiration for how we can not only survive, but also grow, as individuals and community.

And they weren’t alone. Because local queers have worked for decades in other areas to create a caring community — affordable housing, harm-reduction programs, wellness programs, spousal abuse and the response to breast cancer and prostate cancer.

Success in our response to HIV and AIDS has been due to many individuals and groups. AIDS Committee of Ottawa, Pink Triangle Services and Bruce house played a vital role, year after taxing year. Their boards of directors are unsung heroes who kept things moving despite often intense public scrutiny, criticism and financial stress. PTS deserves special kudos, because it has repeatedly spun off new groups when the need arose, often handing over money and talent in the process.

We must remember, too, that there were straight allies, many of them, and many who risked much in their careers, reputations or personal goals in order to work with us. They play a minor role in this recounting, but they did not play a minor role in the life of our community.

This telling of our history names many individuals, and it is individuals who make up groups. But we acknowledge that nothing of substance is ever achieved by one person, acting alone. Our community’s response to AIDS, and the other challenges noted here, was a collective response and we’re wiser to remember this always.

This telling will make errors. Any accounting of our history has subjectivity built into it. And there are errors of omission, people who did important things and were overlooked. For this, the writer humbly apologizes. These were chaotic years, and there will be blanks in the record. Please write us a letter to the editor and add to the official record of our history.

Still, with trepidation, this is one writer’s attempt to dare to recount our history.

***

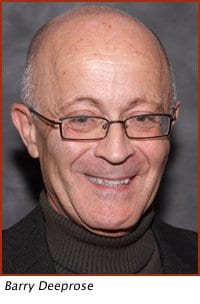

In 1985, the AIDS Committee of Ottawa was spun off from Pink Triangle Services, with the board agreeing to a suggestion made by Barry Deeprose. Years earlier, Deeprose had helped found Pink Triangle Services, and has been the single largest driving force behind the local gay community’s response to AIDS.

Deeprose has help from a PTS board member named Bob Read in setting up the AIDS Committee of Ottawa. Read takes on prevention education while Deeprose works on services delivery, like the Buddies program he establishes. Read’s merry band of AIDS prevention workers does condom blitzes in the bars. Read is a great hero in our community, but died of AIDS. His name lives on, on the door of a room at PTS.

In 1984, a French and a US doctor simultaneously discover that AIDS is caused by the most incredibly complex virus ever found. The next spring, a test for antibodies is put into use in the US; in bureaucratic Canada, its use is delayed until the fall. That needless wait is pure torture for gay men kept waiting to find out their health status.

Meanwhile, people are getting sick, and Deeprose’s band of buddies helps bedside and in doing household and shopping chores. It is taxing work, partly because the hospitals are useless, pushing very ill people out of the door, after humiliating them by needlessly dressing like astronauts while around them. Information is lacking. Nobody knows for sure if you can catch this new disease from people, and yet people in our community volunteer to give very personal care.

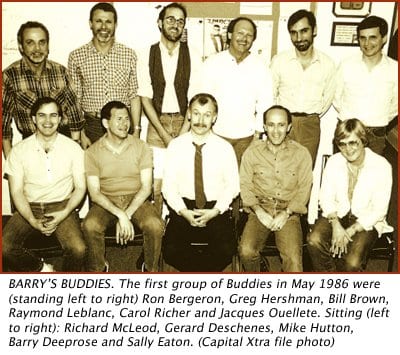

A palliative care chaplain named Sally Eaton distinguishes herself helping in every way she can, for years. Ron Bergeron, a pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church, also plays an important early role. Ron dies of AIDS in 1990.

Deeprose’s band of buddies include: Bergeron, Mike Hutton, Bill Brown, Raymond LeBlanc, Carol Richer, Timothy Andradé and André Lachance, among others.

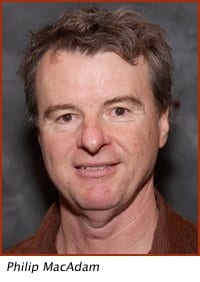

It’s also important to acknowledge the people on that first ACO board of directors. They are Jean-Louis Bouchard, Dr George Parry, and the very helpful straight allies Dr Lothar Huebsch and Dr Bill Cameron. Soon joining them is esteemed local gay lawyer Philip MacAdam.

By Oct 9, 1985 the first community information meeting is held, chaired by Deeprose and with Dr Gilles Melanson as the source of information for people with questions. Dr Melanson is the first out gay doctor in Ottawa. The room is literally overflowing. The meeting is held a month before the virus test is available in Canada and you can imagine what the people in that room are thinking.

The next year, the Canadian AIDS Society is established, in Toronto, to coordinate a national response to the virus. Then the Ontario AIDS Network is founded to support local organizations and activities — and Deeprose becomes its first chair a few years later. The AIDS Committee of Ottawa also moves ahead, with Dr Melanson as first chair. They fight off an attempt by a government scientist to start a rival organization with the same name, and eventually abandon distributing a T-shirt with the logo Play Safely because the War Amps felt it hurt their Play Safely program for kids. Strange times.

Philip Hannan, who later goes on to work for several AIDS groups, and for Capital Xtra, concentrates on preparing pamphlets and other work for the Education Group at ACO. He is joined by Ben Murray as education coordinator, among others.

Nineteen Eighty-Seven is a big year. People are dying. PWAs create their own support groups. And turn their rage at government inaction into a potent political weapon. Prevention efforts at the local level take a jump — in Ottawa, activists distribute Captain Condom pamphlets aimed at teens.

Gay men and their supporters across the developed world are furious at the slow response by governments to the AIDS crisis. Not nearly the needed money is being spent on research, prevention programs or help for Persons Living With AIDS. ACT-UP — the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power — forms chapters in major cities in Canada and the US. In Toronto they are called AIDS Action Now. Their civil disobedience makes TV headlines and helps educate middle-class voters.

Ironically, just as in the Stonewall demonstrations of two decades earlier, some gay leaders oppose the confrontational tactics, bleating that it will set things back. It’s hard to imagine how far back things could be set. But, just like in the case of the 1969 riots, the wimps in the leadership are proved wrong: the expression of justifiable rage makes a difference and moves things forward in terms of funding for research, prevention programs and treatment.

The first drug against HIV, the very hard-on-the-system AZT, goes into use in early 1987. In May, Brian Wilson, who is living with AIDS, founds the first local group specifically to serve those with the virus. He runs it out of his house, calling it 5662 Services, the last digits of his telephone number. It provides one-on-one counselling and groups to get involved in. Eventually it morphs into the Good Time Girls and, eventually, after ACO hires Don Walker to do a needs assessment, it evolves into the Living Room at ACO, managed by Walker. Wilson dies in 1990, Walker in 1991.

Others take a leading role in the early years of the Living Room. George Mitchell starts Girls’ Night Out from there. Lee Lecuyer and Bernie Mathé are also involved in organizing it. They’ve died since.

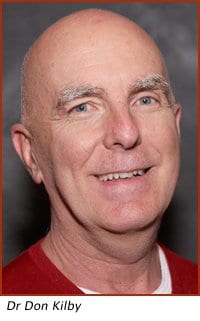

Doctors also play a vital role in supporting people living with the virus. A select few across the nation get involved in making sur

e the health care system responds properly. One is Ottawa’s Dr Don Kilby. He’s given care to many hundreds patients with HIV/AIDS in over 20 years of practice and continues to do so. He’s also worked behind the scenes, as past chair of the Ottawa-Carleton Council on AIDS and current co-chair and longtime member of the Ontario Ministry of Health’s Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

In 1987, the province gives $164,000 to set up ACO and provide prevention and health services. ACO hires Grant MacNeil as interim executive director to get the ball rolling, and then in March of 1988 brings on David Hoe permanently — he stays until 1992. Five staff are hired that first year. We want to pay particular tribute to the work of Michael Graydon, who starts as a volunteer at PTS in 1990 and goes on to be the first Gay Men’s Outreach Worker and, after he leaves ACO, a researcher. Bruce House starts up in 1988 as a spin off from ACO, founded by Todd Armstrong, who dies in 2003.

Now, all this work is not going on against a tranquil political backdrop. Political parties are not setting speed records in embracing the measures needed to solve the crisis. And individual politicians are advancing their careers by making ignorant, and frankly bigoted, statements. Ottawa’s politicians are among the worst in Canada.

Andrew Haydon, former chair of regional council — who sadly has the current city council chambers and a park named after him — fights AIDS funding, arguing it is for a “specific group” and that “It is just another disease … only it takes longer to die.” And he calls for compulsory testing of homosexuals, a measure that politicians in 1940s Germany would have been comfortable with.

And who can forget the ever-charming Jackie Holzman, then alderman but later city mayor (and the brains behind the current mayor’s election campaign). Holzman votes against regional funding for AIDS. Her reasoning: “It is up to people to assume responsibility for their own health and people who have AIDS are going to die anyway.”

But the world is changing and Haydon and Holzman’s attempts to play to the most conservative elements of society backfire. Federal Conservative Health minister Perrin Beatty slaps Haydon down over his call for compulsory testing. And the public outcry against Holzman’s comments delay her appointment to the district health council. Gradually, most people are being touched by AIDS as relatives and co-workers die or get sick, as activists call attention to this crisis that seems to single out the young. AIDS activism is corroding the bigotry of society even as so many of us die.

One of the important early victories of our community concerns Ian Gemmill, the city’s Medical Officer of Health. Gemmill gets court orders prohibiting dozens of HIV-positive gay men from having any sex with others. His outrageous behaviour contrasts with his peers, who are getting similar orders against just a couple of people yearly across the entire province. The outcry over Gemmill’s patent disregard for both science and human rights ends up with his leaving his job.

But there is also destructive politics going on within our own community. Some lesbians, and a few gay men, object to a frank visual that is part of a prevention ad that ran in GO Info, the newsletter of Gays of Ottawa in 1988. The outcry sucks up way too much energy and the issue is not resolved satisfactorily. Ottawa’s queer community lags behind on this issue; other Canadian queer communities more quickly understand that sensitivities and sensibilities are irrelevant when you’re trying to save lives and that images of hard-ons are nothing to get upset over.

From 1988 to 1992, the first generation of AIDS activists and helpers is starting to pass the baton, with successive resignations from ACO and ever more clients dying.

In 1989, Glenn Janzen brings the AIDS Quilt to Ottawa, where it is viewed by some 4,000 people. In 1994, he helps Barry Deeprose organize a national conference of gaylines called And Now Can We Talk About AIDS. Glenn dies a few years later.

In 1989, ACO leads the movement to get anonymous HIV testing in the province. This is vital to create an incentive for gay men to get tested. Until then, the virus is treated virtually like typhoid, a highly contagious disease that can be caught by breathing the same air or light touching. Of course, that does not reflect the reality of AIDS, a virus that takes some serious bawdywork to catch. The victory in 1992 of anonymous testing is a perfect example of how our community has brought a more rational mind, as well as a bigger heart, to our health system.

In 1990, ACO provides seed money for the foundation of BRAS, Bureau Regionaux d’Action SIDA) in Hull. The founder is ACO board member André Lemieux, who dies the next year.

In 1991, the first From All Walks of Life takes place. Bad weather is blamed for a disappointing turnout. But its successor is with us still, and doing much better.

Starting in 1992, an unfortunate trend emerges in Ottawa, and across Canada. The focus of government funding, and indeed of our own community, shifts away from gay men, who continue to be one of the most at-risk groups for the virus. There are other groups that also needed attention, that’s for sure. But it’s done at the expense of reaching our community.

In February 1992, Deeprose resigns from ACO because the group has moved away from its key mandate — preventing AIDS in the gay community. The organization shifts its gay focus from prevention to working with those who already have the virus. But prevention programs remain for other risk communities — street-involved people and intravenous drug users in particular. Deeprose’s resignation is poignant, seeing as he had created the early programs to serve PWAs. But Deeprose keeps his eye on the ball while others get lost.

New organizations and programs emerge to serve at-risk populations like the well-funded OASIS centre for street people and women with HIV. And the free needle-exchange program.

That spring of 1987, David Hoe and Bob Read also leave the group, for their own non-controversial reasons. Hoe continues to work in HIV, chalking up a truly impressive record of work. The organization experiences staff turnover and the entire board resigns at one point. Homophobia in the Living Room drives out gay clients. With this going on, the Ottawa gay and lesbian community largely withdraws its support from ACO.

Meanwhile, the incidence of HIV among gay men begins to rise. A terrible decade passes, a lost decade, a decade in which a small number of gay men labour to get their community’s priorities back to the table.

***

A new philosophy emerges in the mid-1990s, initially advanced by the writings of Eric Rofes in the United States. It is about gay men not seeing themselves as vectors for disease, and about AIDS work not focussing just on the condom and the virus. It is a philosophy of wellness, of seeing health as more than the absence of disease, of building supportive community and creating a reason for people to want to take care of themselves and each other. And it’s about gay men seeing themselves and their culture in an upbeat light.

At one point, Rofes writes: Gay Men are healthy, happy, and life affirming. We’re creative, strong, and resilient; more than almost any other male population, we think outside the box, take responsibility for our actions, and care for our selves and others. We know how to get what we want and we know how to create lives that are satisfying and fulfilling.

Deeprose talks up this approach in local, provincial and national meetings. He chairs a provincial sub-committee that comes up with a strategy combining both care and prevention. Prevention is now officially on its way back to the table.

Building on his successful fight to get gay men’s issues taken seriously at Centretown Community Health Centre, Bruce Bursey heads up a Wellness Survey in 2003. This well-funded needs assessment of 826 queers makes recommendations for services, resources, and organizations to address the strong sense of isolation that the survey clearly identifies among participants.

About the same time, the Gay Men’s Wellness Initiative responds to an outbreak in local syphilis. Mary Gordon of Ottawa Public Health starts a discussion that ultimately, over the course of six months or so, brings 13 groups and individuals to the table. Their focus: a rejuvenation of prevention work and a shift to a holistic wellness approach, including a smoking cessation program aimed at gay men and eventually lesbians. The group is chaired by Deeprose and Kevin Muise.

Again, about the same time, the Ottawa-Carleton Council on AIDS is coordinating the response to the virus locally. A strategic planning process is begun, and local lesbian Anne Wright is hired as a consultant. The resulting report calls for the approach to change from sprinting to a marathon. The strategy — we’ll call it the Marathon Study — proposes that efforts refocus on the demographic groups most at risk, and returns gay men’s prevention programs to the centre of any health response.

Their work is overtaken by a 2004 provincial AIDS Bureau initiative that requires local AIDS strategies evolve from community partners, and focus on prevention and wellness. The Ottawa Carleton Council on AIDS then adopts the recommendations of the Marathon Study to focus on vulnerable populations. Of course, Ottawa has been heading this way and just needs the green light to hit the gas. The light turns green.

Of course, the work toward a fully integrated strategy of wellness and prevention should not be underestimated — it’s a huge ship to turn around on local, provincial and national levels.

A couple of follow-up notes. The Ottawa-Carleton Council of AIDS gets re-named the Ottawa Coalition on HIV/AIDS and plays a leadership role in setting priorities, and supporting sometimes controversial programs, like the needle exchange program and the crack-pipe distribution program. Ron Chaplin now chairs the council, and has joined with ACO in fighting city council’s recent shameful move to stop funding the crack-pipe program.

As a result of the 2004 re-focus on prevention, the provincial government is funding two-and-a-half positions at ACO and Pink Triangle Services that concentrate on gay men’s wellness and prevention campaigns. The feds are funding another. You may know those people — Adam Graham at ACO, and Rick Barnes and Corey Wang at PTS. And Nicholas Little at ACO. As well, ACO has re-engaged with the gay men’s community. Indeed, executive director Kathleen Cummings has promised to find the money to continue the focus in future — with or without government funding.

Our community response to the AIDS virus, our work to shift to a focus on prevention and wellness, is not over. Hundreds have died locally from the effects of the virus since 1984; hundreds more live with the virus, refusing to be categorized as victims. An estimated two gay men a week catch the virus in Ottawa. The work continues.

This history owes its origins to the research of Barry Deeprose. In addition to his often cited work in co-founding Pink Triangle Services and the AIDS Committee of Ottawa, and his on-going work in gay men’s health and wellness, Deeprose has catalogued our community’s history, especially its response to this serious health crisis. Many thanks.

***

Creating a caring community

ACTIVISM / There’s more to this than AIDS work

While gay men in the queer community focussed on their response to AIDS and the recent move to wellness issues, other issues are also being addressed.

Local queers work on a wide range of wellness issues: survivors of sexual abuse, spousal abuse and prostate cancer. Also, housing and social services and community-based health care.

Queer activists, mainly lesbians in Ottawa, work to make sure there’s a home for each in our community. Last year, Capital Xtra honoured two longtime housing advocates with Lifetime Achievement Awards. Catherine Boucher makes a special efforts to reach out to lesbians and gays with the coop, Centretown Citizen’s Ottawa Corporation, CCOC. Linda Wilson is one of the founders of Abiwin co-op, which is dedicated to providing housing for queer people and their allies in a safe and supportive atmosphere. And Rob McDonald is the executive director of Housing Help, a service that helps house many “hard to house individuals.”

Two outreach workers to the queer community have distinguished themselves with their extraordinary work at the city’s Sexual Health Centre, including keeping our issues front and centre: Christiane Bouchard and Rick Dias.

Our community faces some of the same problems of violence as others. As well, some lesbians and gays work on social and health issues that affect other communities even more than our own. Nicole Deschene is one of these. Nicole sat on the boards of Harmony House and Women’s Place for many years, creating safe spaces for women touched by domestic violence. She received a Lifetime Achievement Award last year for her work.

AIDS is not the only life-threatening disease our community faces. We are vulnerable to all the usual health traps that lie in wait. But sometimes, when someone in our community gets a disease, there are challenges that reflect our sexuality. And sometimes there are difficulties sharing those particular challenges in a support group made up overwhelmingly of heterosexuals. In some cities, there are lesbian-only breast cancer support groups, but we’re not aware of one in Ottawa. Maybe a reader is interested in starting one.

But there is a support group for gay men with prostate cancer, and it was started by Bruce Bursey, who is better known for his work on the 2002 Wellness survey.

Finally, there are new challenges facing us with the diversity that is emerging in the queer family. Oh, what a wonderful time it is to reinvent the definitions of family. With that come unique needs and programs. Emily Troy has distinguished herself in her work with Rainbow Families.

Whatever the area, the queer community is working to change the world to reflect our realities. Like summer camp. The folks behind Ten Oaks, are reinventing that fine Canadian childhood tradition to make it a fun place for queer youth and the children of queer parents. This brilliant idea was spearheaded in 2005 by Ottawa’s Holly Wagg and Julia Alarie.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra