In the summer of 2019, I modelled nude for 150 photographers in the woods of rural Ontario. I’d never met them before. And I’d never modelled before. But I was ready to strip.

If I could help just one person, it’d be worth it.

My husband Raj is a photographer. At the time, he’d been taking intimate portraits for a few years, and signed up for a photographer’s retreat full of craft and business classes. They were looking for more queer models, so I signed up, too.

I’ve been out as queer for as long as I can remember, but realizing I’m trans took longer. (It really helped when a lover called me daddy.)

In the early stages of my transition, I found Loren Cameron’s Body Alchemy, a book of portraits of trans men. I was mesmerized. I wanted more. I searched for portraits of trans men of different shapes and sizes, looking for a possible future me: What might my chest look like? My shoulders? My thighs? The space between my legs?

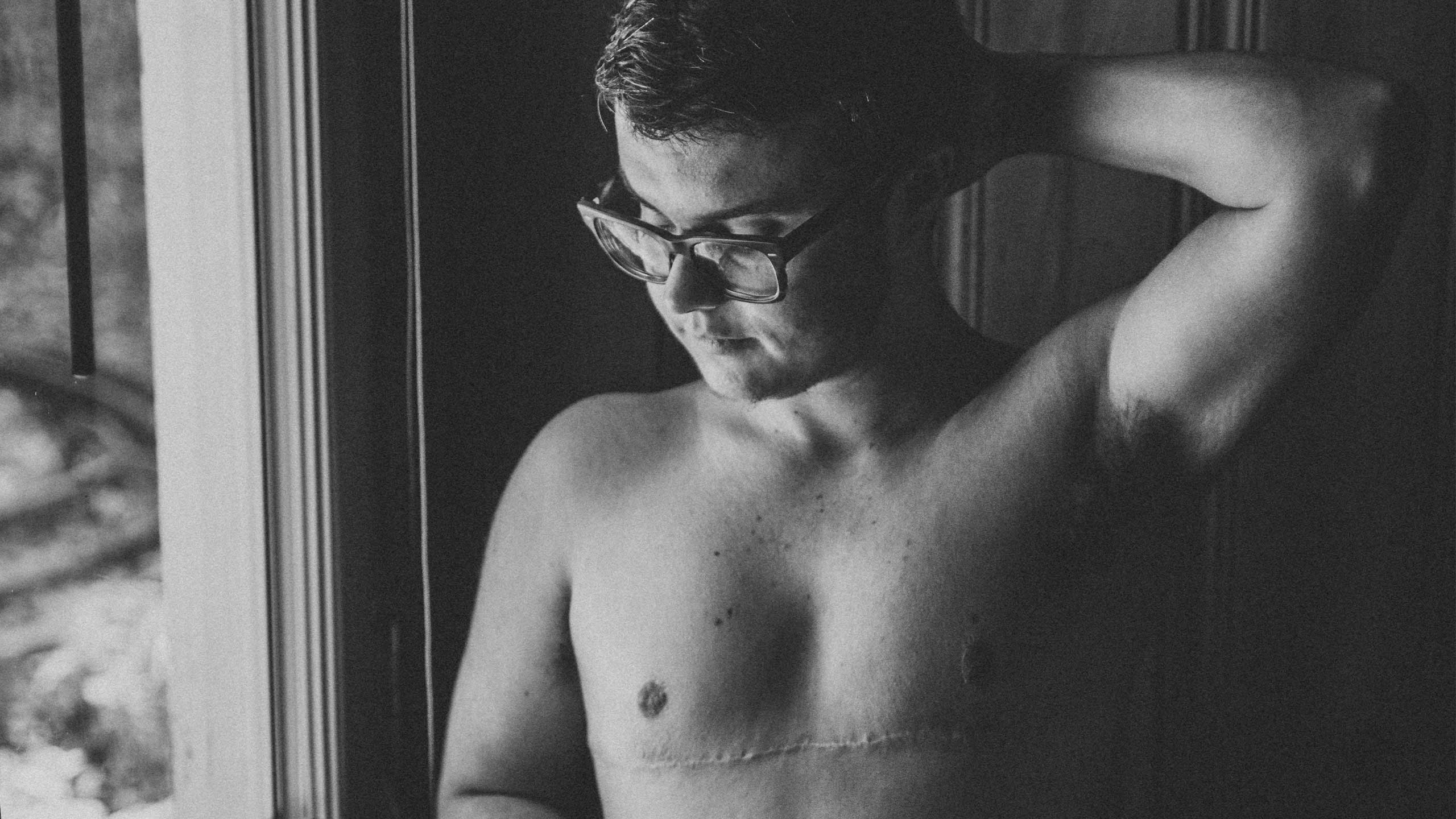

It was easier to find portraits from the waist up: the classic photo of someone enjoying the beach for the first time after top surgery, a solemn portrait of someone “displaying his mastectomy scars” in the New York Times, a friend’s contribution to the Bare Chest Calendar. Elliot Page hadn’t come out yet, and neither had his thirst traps.

So I thought modelling nude might create the images I wish I’d had early on.

At the retreat, I had three jobs: give a queer sex ed 101 talk to the attendees, model for an LGBTQ2S+ shoot and model for a class called “Male Nudes: Shooting Genderless.” The class was taught by Boon Ong, a photographer whose intimate, vulnerable portraits have been featured in Contemporary Calgary and other galleries.

The queer shoot was first. It was the middle of June, chilly despite the sunshine, and I was too cold to get naked on the docks by the lake. I watched in awe as more experienced models kept blankets and mugs of hot cocoa ready to warm themselves in between sets. I stayed in my T-shirt and shorts and sought out pockets of sun, wishing for once that I was back in Texas with its 35-degree days.

That night at dinner, I got to know some of the models and photographers. I smiled seeing the joy they took in their craft—the attention to lighting, to textures, to mood. But even more than that, I treasured their origin stories. Boon started photographing nudes as part of his coming out process. As others shared how photography helped them heal their own body image issues, I became determined to learn as much as I could over the next four days.

After dinner, the hosts set up a mic and speaker and I welcomed folks to our sexuality panel. I shared a portion of the story of my marriage, defining queer terms and concepts along the way, and took questions from the audience. Raj answered some questions, too, about what it’s like to be a straight man in a queer relationship. I loved every minute of it.

The next morning I arrived early for class, and I asked the photography students what they were hoping to learn. Most said this was one of the few classes on taking intimate, vulnerable portraits of men, and that emotional journey meant a lot to them. We stepped inside a log cabin, and it was time to start.

The first half of class was a lecture to teach core principles and to share examples. The second half was for shooting.

I stripped.

“And when I slid my underwear down, I knew it was the first time many folks in that room had seen a man with my anatomy.”

As I took off my T-shirt, I wondered how they’d react to my top surgery scar. As I pulled off my jeans, I felt acutely aware of the absence of a bulge in my boxer briefs. And when I slid my underwear down, I knew it was the first time many folks in that room had seen a man with my anatomy: a vagina, voluptuous labia and a testosterone-grown cock.

I felt many eyes—and all those camera lenses—focused on me.

Boon asked me to rest on one of the beds, totally naked, in fetal position. I got comfy while a dozen photographers captured my image—naked, small, alone.

My favourite photographs from that pose are from Shawn Moreton. I see a body that’s been through a lot and earned a moment of rest. I see myself with such warmth and care. I want to print and frame these, to remind myself to hold that person, to love that person, to make space for rest.

Credit: Shawn Moreton

After class, I got dressed and went for a walk. I noticed the calm surface of the lake, the deep green of the trees, the breeze against my skin. I told my body, “We are here. We are safe. We are loved.” I held my husband’s hand.

And then Kalvin McClure, a photographer who’d just come out as trans, asked if I’d be up for an erotic shoot. He wanted better representation of trans guys in erotic art.

I wanted that, too. I said yes.

We discussed the specifics of how we’d work together: which activities and pictures were allowed and which were off-limits. We raised our water glasses to each other and set a date and time to meet.

I packed my solo sex kit—dicks, harness, hitachi—and made my way to the cabin we’d reserved. We started with show-and-tell. I gave him a tour of my kit, and walked him through how I use each item.

Then we got to it. I was so thrilled to put on my favourite harness—brown leather and brass from Switch Leather Co., a queer women’s collective in Portland—and the dick that felt most in proportion to my body, a modest Vixskin that retains body heat and feels like home when I’m sinking into someone.

I love the shot of me in the window, delighting in wearing my favourite leather.

Credit: Kalvin McClure

But my favourite is an image of me on the bed using no accessories at all. It’s just me, my fingers and my testosterone-grown dick.

The first time I saw that photo, I gasped and tears came to my eyes. I felt so seen, so celebrated, so loved. It’s a beautiful photo, one that shows bodies like mine in pure joy and explicit detail. It’s hot and it’s art.

Credit: Kalvin McClure

Before transition, I’d read about bottom growth, but there was so much innuendo and so little in the way of photos. I didn’t know what people meant when they said testosterone turns your clit into a dick. I didn’t know that the average clitoral glans is about 0.2 inches long, and the length of the same structure after a few years on testosterone is more like 2 inches. I didn’t know that this new length opened up more ways to get off. I didn’t know it was possible to actually stroke the head of your dick with your foreskin, or to have someone suck you like they would a cis dick.

Maybe if I’d done more research on Transbucket or Reddit I’d have found some selfies showing this. Or if I’d sought out trans guy porn I might’ve seen some examples.

But I wasn’t looking for phone selfies or videos. I was looking for stunning photographs that would inspire awe in anyone, that would belong in a gallery, that would make my gaze linger.

I was looking for role models.I was looking for something in the style of Loren Cameron’s book of portraits, but close up. I was looking for something like Joani Blank’s book of vulva portraits, Femalia, but for trans men. At the time, high-quality medical illustrations didn’t yet exist.

So when I got the opportunity to make the art I wished I’d had, I jumped.

It’s been almost two years since those photos. But every time I look at them, my heart swells with joy and I want to do more.

In her fabulous book, Never Say You Can’t Survive: How to Get Through Hard Times by Making Up Stories, Charlie Jane Anders argues for the importance of writing experiences of joy—especially when you belong to a marginalized population, and especially when the world is totally broken. Sharing joy provides a small glimmer of hope, and builds up our emotional reserves to cope with the anxiety of the world.

I wish I could send these photos to myself 10 years ago, when I was terrified of gaining even five pounds during the stress of a PhD program, saying we’ll be okay.

I wish I could send these to me five years ago, on the brink of divorce due to my impending transition, saying we’ll be okay.

When I see these photos, I’m proud. I honour all that my body has been through and all that it will go through. I tell my scars thank you, for they are what allow me to wake up feeling like myself. I tell my belly thank you, for it keeps me warm and helps me stay nourished. I tell my scruffy facial hair, my size five feet, my small hands and my graying hair: thank you.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra