MC Milton Hochebob and Solange. Credit: Allison Lepp

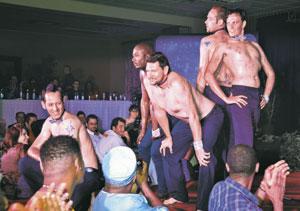

The contestants strut their stuff in a group number. Credit: Allison Lepp

View of downtown Windhoek from surrounding hills. Credit: Allison Lepp

Wendelinus Hamutenya after winning Mr Gay Namibia. Credit: Allison Lepp

I find Namibian musician Michael Pulse stealing a cigarette under the shade of palm trees outside Windhoek’s Event Square ahead of his country’s first beauty pageant for gay men.

Pulse is joined by Milton Hochobeb, the master of ceremonies for Mr Gay Namibia.

While the Mr Gay pageant is the country’s first, Namibia is actually the second African country to hold a similar event. Neighbouring South Africa has held several Mr Gay pageants, and last year’s winner went on to win the 2011 Mr Gay World pageant.

Pulse and Hochobeb assure me that Windhoek, Namibia’s capital city, has a “huge” gay community. “It’s way bigger than you’d realize,” says Pulse. “There’s so many of us.”

But in Namibia, Hochobeb explains, “the black and white gays don’t mix much. This is the first time we’re coming together. We need each other, but we didn’t know how to bring ourselves together, until now. Things are gonna blend tonight.”

First colonized by Germany and then South Africa, Namibia, formerly called South-West Africa, shares its larger neighbour’s painful apartheid past. In many ways the country remains divided along racial lines. Outside the pageant venue, the four white contestants smoke on one side of the patio, while the only black contestant, Wendelinus Hamutenya, joins Pulse and Hochobeb to chat briefly before going back inside to practise dance moves on the catwalk.

With 2.2 million people in a land mass the size of British Columbia, Namibia has one of the world’s least dense populations. According to the Gini coefficient, which measures distribution of wealth within a country, Namibia is also one of the world’s most unequal countries.

The division between rich and poor mostly falls along racial lines. For example, according to the last Namibia Household Income and Expenditure Survey, a German-speaking household has an average income 31 times higher than a household that speaks Khoisan, one of Namibia’s native languages. The National Planning Commission’s Central Bureau of Statistics reported in the 2008 “Review of Poverty and Inequality” that the predominantly black northern regions of the country account for almost 60 percent of all poor households.

Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990. It has since made impressive progress on the issue of women’s rights, implementing laws to tackle domestic violence and rape.

However, it still has a long way to go in terms of gay rights. Mr Gay Namibia organizer Chris de Villiers says he struggled to book a venue for the event. “As this event was a risky first move, we originally planned a closed-door event for a very select few people,” he explains. “But very quickly it became evident that the tickets were in high demand. With the help of our friends, we frantically started looking for alternative venues. One after the other, the venue would be booked, just for it to be cancelled by the landlord a few days later, in some cases with the words ‘We don’t want your kind here.’”

Namibia is a great case study for what it takes to build a tolerant gay-friendly society. Many gay people I have met live openly, and the state does not aggressively persecute them as harshly as other African countries do. Yet it’s clear mainstream Namibian society is still quite uncomfortable with their presence. Homophobic attitudes are subtle: straight Namibian friends will suddenly go silent when I mention Mr Gay Namibia. Same-sex relationships, unlike in neighbouring South Africa, are not protected under Namibian law.

Dianne Hubbard, coordinator of the Legal Assistance Centre’s Gender Research and Advocacy Project, notes that the 1992 Labour Act originally included a provision prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation; however, this provision was dropped in the subsequent 2007 Labour Act. “This is shocking in a nation which has risen from an apartheid past,” says Hubbard. “Surely Namibia should stand for the principle of non-discrimination if it stands for anything.”

Mr Gay Namibia is one of the ways gay Namibians are trying to change homophobic attitudes. The event is meant to promote the spirit of living an open and honest life, and the winner will go on to compete at the 2012 Mr Gay World competition.

The press release for the event reads almost like a manifesto: “By now it should be known that the gay community in Namibia is here, strong and no longer in hiding . . . All the contestants are in consensus that their days of hiding are over, and they feel that it is time that Namibia chooses a role model that can represent our gay community. They are also very aware of possible intimidation but are prepared to stand up and be recognized.”

To start the pageant, each of the five contestants introduces himself to the audience with a short speech. Each speech is highly political, describing the contestant’s ambitions and visions for Namibia’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans communities.

Contestant Herman Feddersen says, “I’m here to stand up and say, ‘This is me, here I am,’ and not be criticized for it. We need recognition. We need acceptance.”

It’s a contrast to the usual “I wish for world peace” speeches of other beauty pageants. The audience seems to still be attempting to absorb the powerful statements when the contestants climb back on stage in swimming trunks for the ubiquitous swimsuit round.

Contestant Wendelinus Hamutenya is from the village of Oshalembe, in the poor northern region of Namibia, where discussion of homosexuality is taboo and being gay is considered unnatural. When his family found out he is gay, Hamutenya was chased out of his home, like many of his gay friends, and put in a mental hospital. But after much dialogue he was reunited with his family, who now support him in his goal to become Mr Gay Namibia.

Before the event I ask Hamutenya if there are many other gay men where he comes from. “I know a lot of gay people up north,” he tells me. “At night they want to talk to you. But then they also tell you, ‘You must act like a man.’”

I inquire about the racial politics of the gay community. As the only black contestant, Hamutenya acknowledges that race issues need to be addressed. “Yes, in this contest there are a lot of white people. Many blacks thought it might just be for whites. So I wanted to do it. I want to do my best not to let them down . . . You see, it would be difficult for a white person to go up north and tell the people there that it’s okay. They would not believe him. That’s why I wanted to go for it. I’m not doing this just to win,” he adds. “I want to be a role model.

“Many people believe that God hates gays, but God does not hate anyone,” he continues, quoting a verse from the Bible: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

Hamutenya’s steadfast faith in a loving God and the compatibility of homosexuality and Christianity is an interesting contrast to the words of many Namibian politicians, who argue that homosexuality is both a result of Western influence and against Christian morals, despite the fact that Christianity itself is a Western influence.

After many costume changes, a group performance of “It’s Raining Men” and Pulse’s beautiful rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” the competition winner is about to be announced.

A drag queen named Solange has been tasked with the job. She knows how to play the audience members, who are anxious to see who will win.

“And Mr Gay Namibia 2011 is . . . Wendelinus Hamutenya.”

The entire room erupts in celebration.

Hamutenya’s fans rush the stage and fill the air with ululations. As Hochobeb predicted, the audience has indeed blended, with black and white Namibians cheering together in excitement.

A large man beside me holds a giant rainbow flag and jumps up and down screaming. As ABBA’s “Dancing Queen” plays, Hamutenya is presented with his Mr Gay Namibia sash. He stands at the front of the stage with a thoughtful smile on his face.

A week after winning the Mr Gay Namibia title, Hamutenya was brutally assaulted by two men near his home in Katutura, a black township outside Windhoek. The men demanded he hand over the money won at the competition. They then kicked him to the ground, dealing blows to his head and ribs before making off with his cash. Hamutenya was hospitalized for 24 hours.

Hamutenya says he was aware something violent might happen to him after the contest. I passed him a few days later in the street. He looked beautiful and was walking tall and proud. He told me he will continue with his duties as Mr Gay Namibia and he has no intention of letting the incident get in the way of his dream of seeing a more accepting Namibia.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra