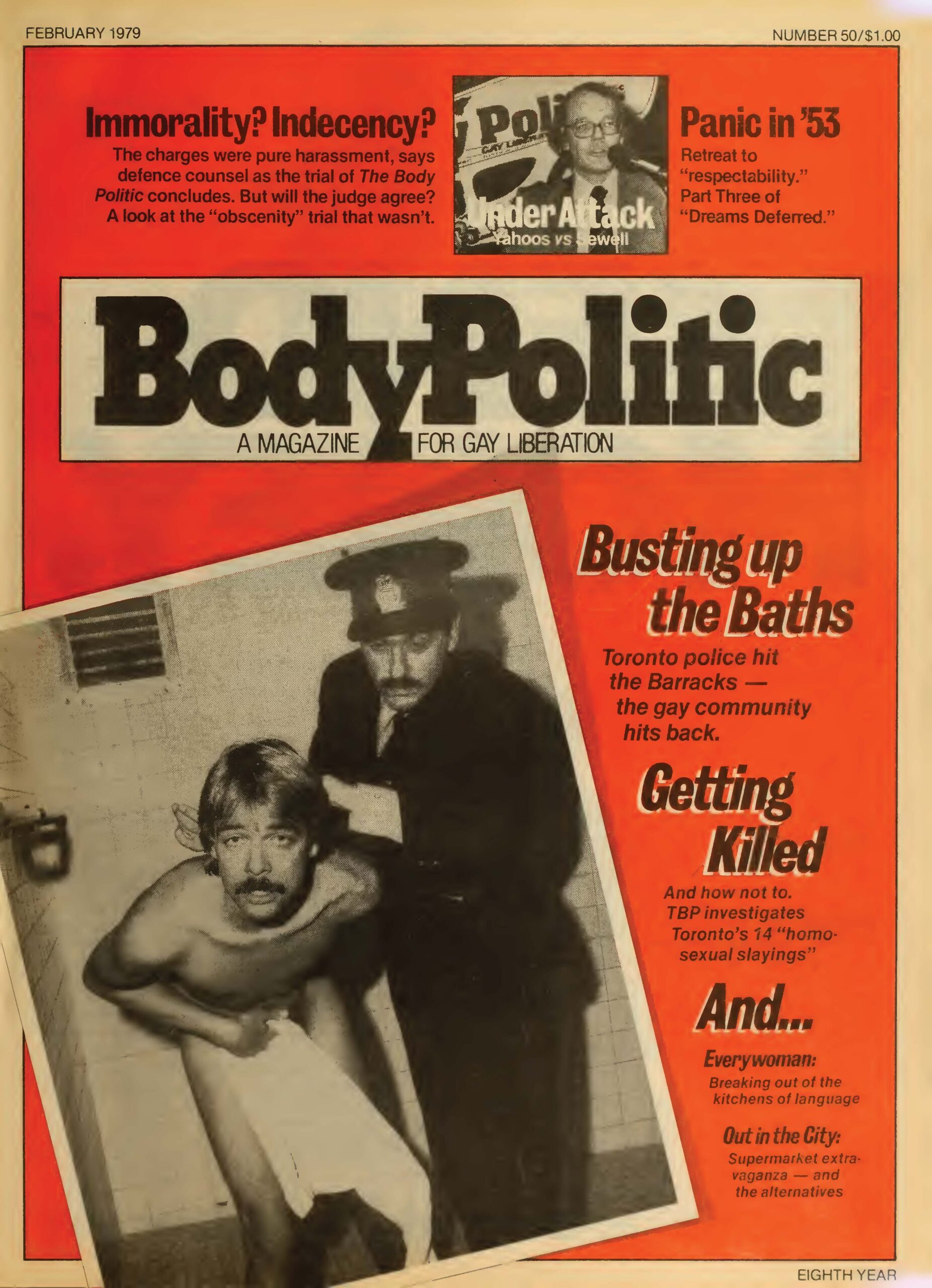

In February 1979, Robin Hardy wrote about the mystery that plagued Toronto’s gay community in the mid- to late 1970s: the murders of 14 gay men in four years. At the time, eight of the killings remained unsolved.

It’s been almost 40 years since Overkill: Murder in Toronto-the-Good was published in Xtra’s predecessor The Body Politic, and yet it seems much of what was discussed in the feature has not changed: police have continued their legacy of dismissal and discrimination when queer people are the victims of crime; violence against LGBT people is just as prevalent; media, police and society still believe homosexuality is a lifestyle choice and that the danger lies in cruising and bar scenes; and gay men who are closeted and isolated are still targets of heinous acts.

But the most important theme of Hardy’s feature is how community and friendship hold everyone together in the wake of tragedy.

William Duncan Robinson has been described as a quiet, shy man who lived alone. Robinson was last seen at 2:30 am Sunday, November 26, 1978. He was leaving the St Charles Tavern, a downtown Toronto gay bar, accompanied by a tall, lanky man with dark brown greasy hair,

sloping shoulders, large dirty hands and feet, and an offensive body odour. Robinson’s companion walked clumsily and was scruffy in appearance. It’s hard to imagine why anyone would take him home.

Late Saturday night, a neighbour of Robinson heard a “peculiar loud hollow noise.” When another neighbour passed Robinson’s door around 9 PM Sunday night he heard nothing. An hour later he passed the door again, and heard the stereo blasting away.

“On Tuesday November 28,” the police bulletin reports, “the lifeless body of William Duncan Robinson was found in his apartment situated at 205 Vaughan Road, Apt No 32. The cause of death was determined to be as a result of stab wounds to the chest.”

The murder of Duncan Robinson achieved notoriety as the fourteenth “homosexual slaying” in Toronto since 1975. Eight of those murders are unsolved.

It has made great copy for local papers: “Homosexuals fear mass killer,” “Slow hustling on homosexual row,” “Murders put homosexuals on guard,” and “14th murder chills city’s homosexuals.”

The rumour factory ran overtime: the killer is the father of a 14-year-old boy who became involved with homosexuals and has vowed “the revenge killings will continue”; the murderer is a sickie on the loose; the murderer is someone quite involved with the Toronto gay community.

Shortly after Robinson’s murder a message was scrawled on the wall in the washroom of the St Charles Tavern: “I’ll kill again Saturday night.” During the same week, on the graffiti board at Buddy’s Backroom Bar, someone wrote “Billy is next.” Billy, a waiter, was understandably worried. A University of Toronto professor active in the Damien Committee and the Gay Academic Union received by mail a clipping about the unsolved murders torn from the

Toronto Star. Typewritten across it were the words “You’re next.” It was postmarked Malton, a Toronto suburb.

The series of unsolved murders begins in 1975. On February 18, the body of Harold Walkley, a 51-year-old history teacher and community activist, is discovered by his roommate in Walkley’s bloodied bedroom. He is nude, and has been stabbed several times in the back and chest. No knife is found and credit cards have been stolen.

A year later, on February 11, 1976, James Taylor, a 41-year-old painter and decorator, is found in his home, beaten to death with a baseball bat. Another six months, and on September 20, 1976, the caretaker finds 49-year-old James Kennedy dead in his apartment, nude, with a towel knotted around his neck. He has been beaten about his face. Again, credit cards are missing. Kennedy’s neighbours describe him as “a recluse.” Kennedy was last seen at the St Charles Tavern the night before he was killed.

Six months pass. On January 25, 1977, the nude body of Brian Latocki, a 24-year-old bank analyst, is found in his blood spattered bedroom, he is tied to the bed, his head badly beaten. He has been strangled and stabbed. Again, no knife is found. An autopsy determines that his death occurred January 22. The night before he had been seen hitch-hiking home from the St Charles Tavern. Latocki is described as “shy and new on the gay scene.”

These murders have not been solved. Nor do police know who murdered Fred Fontaine, Donald Rochester, and Sandy Leblanc. Fontaine was severely beaten in the washroom of the St Charles Tavern on December 20,1975, and died in hospital six months later. Rochester was shot dead February 13, 1978, while on duty as a night porter at the Toronto Lawn Tennis Club. Police suspect a “homosexual connection” in this death. Sandy Leblanc, a well-known club owner on the Toronto gay scene, was found dead in his apartment September 21, 1978. He had been stabbed more than 100 times from head to foot. As police walked around the body, the carpet squished from the sound of absorbed blood, and bloody footprints led to an open window. It takes a lot of time to stab 100 times through flesh and bone.

Credit: The Body Politic/Pink Triangle Press

With eight of the fourteen murders unsolved, belief in the existence of a single psychokiller is widespread. But police are encouraging the theory that the murders are unconnected random

killings. This means there could be eight killers “out there” somewhere.

Until the murderers of the eight men are found, little will be known of the circumstances which led to their deaths. Of the six murders which have resulted in arrests or convictions, six different people have been proved or alleged to be killers.

The “solved” murders have involved robbery, fights over payment for sex, and violent assault resulting, unintentionally, in death. They prove one thing: death by murder is unpredictable, and the reasons for it are usually quite banal.

There are enough similarities between the “solved” murders and the unsolved ones to indicate that just as there were six killers in the “solved” cases, there could well be eight killers for the unsolved murders.

The element which runs most consistently through all fourteen deaths is “overkill.” “Overkill” means that the victim is repeatedly stabbed, bludgeoned or beaten even after death. Inspector Hobson of Homocide Division, Metropolitan Toronto Police, appears helpful, but has an abrupt manner. He refuses to connect the unsolved gay murders. “In several of the murders there is a common denominator: the victim was last seen at the St Charles Tavern, and met his murderer there. Beyond that we cannot say if there is a connection. We don’t even know if there was robbery in all the cases. Often the victim lived alone. Sometimes a relative could say something was missing.”

But Inspector Hobson admitted there was much information he was not revealing. It was more a case of “we’re not telling you,” than “We don’t know.” If someone is brought in for the crime and a confession is extracted, the police need evidence to corroborate that confession in court. Corroborating evidence must be material not known to the general public. Hobson refused to say how many murderers the police were looking for in the eight unsolved cases. He also refused to say whether or not police knew if the men had been killed before or after sex. In the case of Duncan Robinson, he did divulge one piece of information in his possession when he let drop the comment: “I guess the killer can’t change his bloodtype.” Police found blood samples to indicate the killer had been injured. Robinson fought back.

The question the police should answer is why these murders have not been solved. “We have difficulties with this kind of case,” Hobson said. “First, it seems that the pick-up is made just before closing hours. The victim is seen with his pick-up only for a very short time, and by witnesses who have been drinking and who are going home. They have hazy memories. I just wish people, not only gays, were more observant.”

A Toronto newspaper, using the murders as yet another indictment of the gay lifestyle, reported the problems the police had in the “murky, secretive world of gay bars and discos.” Apparently two policemen, “disguised” as lovers, haunted gay bars for a month to find the murderer of Neil Wilkinson, who was beaten to death in his apartment in December, 1977. But Inspector Hobson said the gay community has been most helpful in coming forward with information. The composite drawing of the suspect wanted for Robinson’s murder was compiled from descriptions given by witnesses at the St Charles Tavern.

Yet even as police encourage gays to come forward with information on the eight unsolved murders, they spend energy criminalizing gays by raiding the baths, one of the safest places to have sex. John Allan Lee, gay sociologist and author of Getting Sex, disagrees with any police analysis which says there is no pattern to the murders, although he doesn’t suggest there is necessarily one murderer. He believes the victims fall into one of two categories. “In the first category are young men who are incapable of safe cruising. They are shy, don’t know how to talk to people. The second category is made up of desperate. unattractive and usually older men.” Probably the two categories overlap. Lee was a friend of the first victim in the series of fourteen murders, Harold Walkley. Walkley’s murderer has not been found.

“Harold fell into the second category,” said Lee. “For some time before his murder he would take anyone home. He was getting older, losing his looks and was lonely. He had difficulty finding lovers he could be compatible with. By the time closing hour came around at a bar he would settle for anything. I was at a party he attended just before his death. Someone put on a record with the words ‘You’re nobody ’til somebody loves you /So find somebody to love.’ Harold stood up and yelled, ‘Yeah, and how do you find someone to love?'”

These are old and weary stereotypes of gay men, but they still have some basis in reality. There are older men who grew up long before the renaissance of gay liberation, men who internalized the vicious myths of the aging, unhappy, friendless gay man. And there are younger men who, unsure of their gayness, cautiously begin to leave their isolation in the straight world. As more gays come out, Lee believes that the number of victims in this category will increase. “There is more homophobic violence to come. It’s almost like the second law of thermodynamics: for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. A reaction is forming to the social movements of gays and women. These movements are ones which seek concessions. It hurts people to concede things. It is, for example, no coincidence that rape statistics increased dramatically when women entered the economic system. As more gays make their presence known through marches or protests or what have you, more people are going to react and act out against gays.”

Lee thinks the murderers are more likely to be repressed homosexuals rather than homophobic and violent straight men. “The killers of these gay men may themselves have a predisposition to homosexuality. However, they have been trained to hate homosexuality. In destroying someone they’ve gone home with, they kill that part of themselves. They are filled with self-hatred.”

Dr Dan Paitich, senior psychologist in Forensic Sciences at Toronto’s Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, also doubts the unsolved murders were the work of one psychokiller. But Paitich disagrees with Lee that the murderers are repressed or latent homosexuals.

“This is an aggressive homophobic situation. These killers, as far as any profile can be made, are homophobic, derelict, from a low social class or the criminal subculture; they are poorly educated and likely alcoholic. Overkill is a sign of drunkeness and of the tremendous rage released. But there has been no real research on this kind of thing in relation to the murders of Homosexuals.”

“If these murders are done by different men it may be a case of the homosexual being attracted to an aggressively masculine drunk and thereby putting himself in a potentially dangerous situation. But the motive may simply be robbery — and hatred of the victim after the robbery has taken place.”

George Hislop, a leading spokesperson for the Toronto gay community, has followed some of the solved murder cases as they went through court. Said Hislop, “One thread I see running through most of these cases is that they originate in Yonge Street bars, and that the murderer is a person with a background as a hustler, and a history of robbery, drugs, and alcohol. There are some men out there who simply want to rob and commit violence against people. They use a sexual advance — or one they fabricate later — to justify the violence they are already planning.”

Three of the solved murder cases seem to support that theory. The killing of Earl Cross by Bradley Benoy in December 1977, may not have been a homosexual murder at all. There was no evidence in court that either was gay, and Benoy spun several strange yarns to explain who killed Cross. That Cross had made sexual advances may simply have been one such yarn — newspaper reports have never made this clear.

When James Walker murdered Neil Wilkinson, also in December of 1977, he told police he was provoked by Wilkinson’s sexual advances and his fantasies of having intercourse with young boys. This occurred at a time when the murder of Emmanuel Jaques, the 12-year-old Toronto shoeshine boy, was fresh in everyone’s mind. When it was shown in court that Walker had been naked in Wilkinson’s apartment. Walker was driven to the absurdity of saying he had taken off his clothes to “avoid Wilkinson’s sexual advances.” The prosecutor established that Walker had gone to Wilkinson’s apartment with an intent to rob. The stories of sexual fantasies were merely desperate attempts on Walker’s part to mitigate the gravity of murder, and lessen his culpability.

When 19-year-old John Sharkey killed Colin Nicholson in August 1978, he claimed he had been provoked by sexual advances. Nicholson had picked up Sharkey, who claimed he was straight, outside the Manatee, a gay afterhours disco in Toronto. After hitting Nicholson over the head with an iron skillet, Sharkey stole liquor, clothes, money and silver from the apartment. The judge rejected Sharkey’s claims of provocation, saying it was hard to believe the young man did not know what he was getting into. In that trial, the prosecutor made a speech asserting that the two hundred thousand homosexuals in Toronto had a right to be protected in their homes. Sharkey was sentenced to seven years for manslaughter.

Credit: The Body Politic/Pink Triangle Press

A few years ago the courts might not have agreed with the prosecutor of John Sharkey. In the early Sixties, in Guelph, Ontario, a young man was acquitted on a murder charge when he said the victim had made sexual advances. The youth, acting in self-defence according to the court’s ruling, had stabbed the victim 17 times.

The sexual liberation movements of the last 10 years may have made the courts somewhat more careful in their handling of cases of violence against gay people. But gay men and women will be targets for violence and murder until more fundamental changes have occurred in our society.

At the same time, queerbashers whose activities lead to murder, and psychokillers with enormous reserves of hatred for homosexuals, are psychological terrorists, keeping gays discreet and in the closet.

The media, especially newspapers, capitalize on this with lurid headlines suggesting homosexuals are victims of a decadent lifestyle. Of 51 murders in Metro Toronto in 1978 only five — 10% — of the victims were identified as gay in media coverage. It appears, then, that the number of murders of gays is not out of proportion to the number of gays in the population generally. Furthermore, while gay murders seem strongly connected with the bar and cruising scenes, most heterosexual murders are domestic, and take place in the home between members of the same nuclear family. Gay people are no more victims of their lifestyle than straight people.

How not to get yourself killed?

There is no guaranteed way to avoid murder. It’s as much a function of chance as crossing the street or taking an airplane. Basic self-defence training seems one obvious solution, but in Toronto, at least, there are no selfdefence courses available for men, except judo and karate lessons. Handy little items like aerosol mace, available in American cities, are illegal in Canada. But there are ways of avoiding dangerous situations and preparing for emergencies. If John Lee is right in grouping the victims into two categories, it’s obvious that there is one lifestyle which is safer: the lifestyle of the “out of the closet” gay.

A gay man alone and closeted is more likely to be a victim of violence than an individual who accepts his gayness and has developed a circle of sell accepting gay friends and acquaintances. Someone in the closet is likely to pick his sexual partners only after he’s drunk enough to face up to it, and fear of discovery may drive him to select the kinds of men he’s not likely to meet again. If a gay man is open, on the other hand, he ends up meeting many of his sexual partners through mutual friends. Not that most of us won’t be tantalized by strangers and hustlers from time to time — but if there are any doubts, it’s good to remember that sex at the baths is safer than sex at home.

It’s important, even in bars, to develop friendships with other patrons. Part of being out of the closet is the ability to feel comfortable with a gay lifestyle. There should be no shame involved in saying good-night to friends while you make it discreetly obvious that you’re heading home with the hot new friend panting beside you. After that, a psychopath is likely to flee immediately.

There are techniques for screening people which should be a part of every man’s cruising. “I can find out what kind of person I’ve met by talking to him,” says John Lee. “For instance, I’m very wary of people who have no opinions on anything. I met a man once at a bar and we went to have coffee. He began asking me questions about my work, my politics, and my life. Finally I said to him, ‘Are you aware of what you’re doing?’ He said ‘I’m just trying to find out what kind of person you are.’ But unconsciously he was screening me for danger.” In other words, it boils down to humanizing communication in the bar scene.

There are other precautions which can be taken. Those who live alone can pretend they have a roommate, saying to a new friend as he comes in the door, “Shhh, we have to be quiet so we don’t wake up Joe…” But it had better be at least a two-room apartment!

If a person likes a lot of one-night stands, it’s probably a smart idea not to live alone. But those who do should invest in some common sense safety precautions such as alarm bells, an escape route, locks which cannot be picked or pried, and an understanding neighbour to escape to. Again, it’s best to be out of the closet.

Fourteen murders in four years is frightening. Homosexuality may simply be used as an excuse by murderers for robbery and gain. There could be 14 murderers, a terrifying indication of homophobia. Or there may be a psychokiller, coldly anticipating a victim every six months.

Whatever the reasons for the deaths, and whoever the murderers are, gays can protect themselves, and they can help solve the murders as well. Individuals who may be afraid to take information to the police for fear of exposure should give their information to someone more open in the gay community who can pass it on.

James Kennedy, 49, was “a recluse.” Brian Latocki, 24, was “shy and new on the gay scene.” Duncan Robinson, 24, was “a quiet shy man who lived alone.” These men, and eleven others, did not have to die. They were caught in a familiar contradiction: uncomfortable in the gay world because they were not “out”; not “out” because they were uncomfortable with the gay world.

Tragedy cannot be measured, but somehow the deaths of those “shy” and “new on the gay scene” assume a particular significance. The straight world isolated these men because they were gay. It made them outsiders. Just as they reached for their freedom in a community of their people, they became victims of their isolation.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra