I say it for the first time at a social, two weeks after she leaves Boston. The words feel sticky on my breath, almost criminal.

I’m not straight.

Holding my breath, I wait for someone to call me out, to question what right I have to identify the way I do. No one does.

Bisexual. Queer. Not straight. I try on the words like the new button-downs in my closet. They are colourful spirals of panic fluttering in my chest, squirming in delight.

So with bated breath, I practise being someone new.

I come out to strangers.

I knew when we danced together at the club.

We’d done it a thousand times before. Pre-gaming together in her room or mine until our skin burned hot enough to brave the chilly nights; staying close, watching over each other. But that night when she looked into my eyes and smiled, I felt a fist clench in my stomach. Later, I lay awake in my room, my hands retracing the feeling of her waist, her arms. My blood boils bitter with desire I never knew I had.

What’s more familiar is shame. I feel disgusting for wanting what I don’t deserve. Criminal for staying her friend when I crave more.

When I finally tell her, three months later, she’s kind to me. We talk about her, me, us. But she’s leaving the city at the end of the summer. We sit together and I don’t always look her in the eye because I’m afraid of how it makes me feel.

She promises me we’ll still be friends if I can be okay wanting more than she can give me. And then she’s gone. But I’m still here. Alone in the city, sitting in my room with the lights off and tears streaming down my face.

Meeting new people is exhausting, but wallowing alone is more exhausting. I settle for the former. There are plenty of meet-up groups for people my age, and I sign up for as many socials as I can. It feels grown-up.

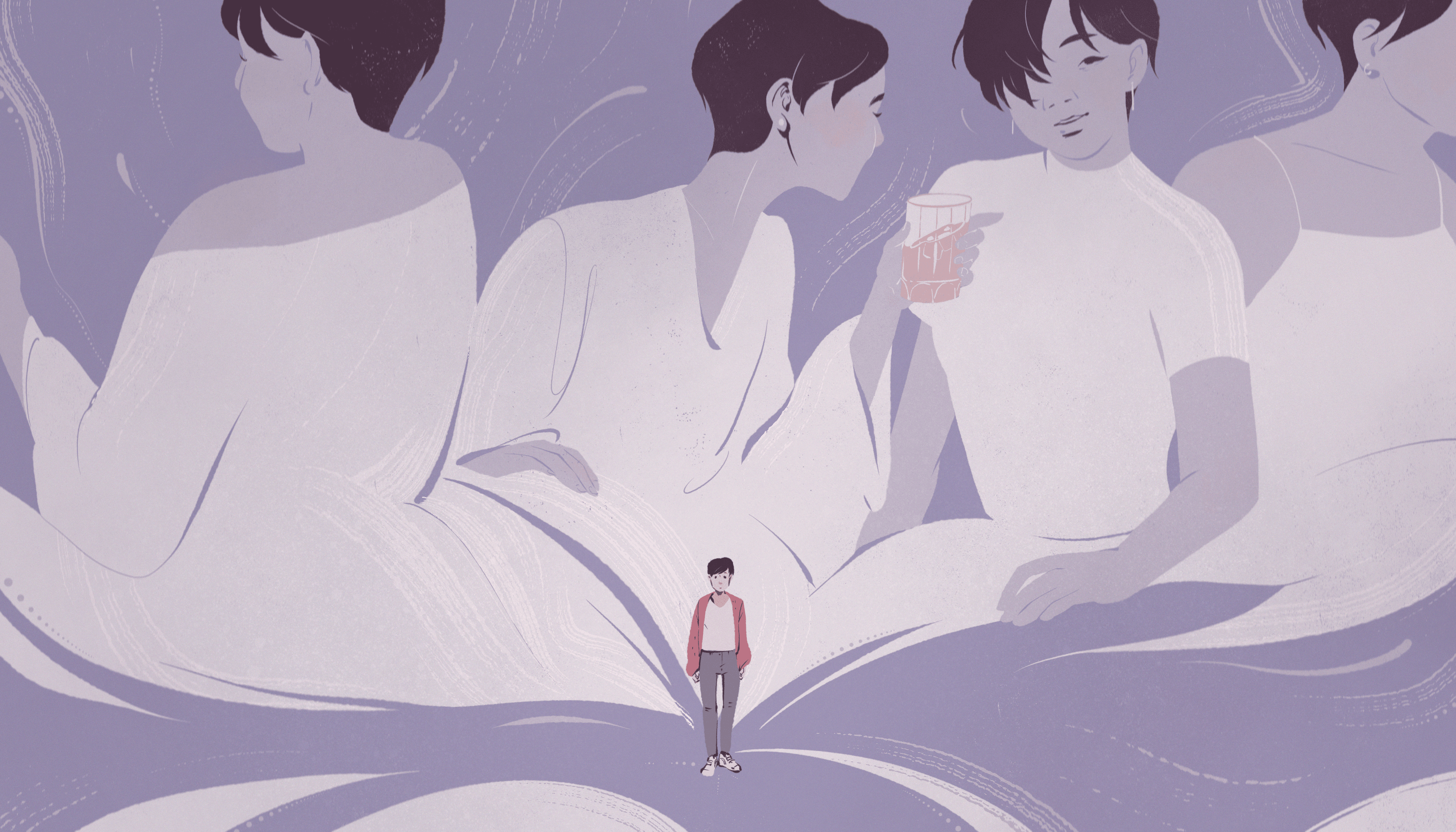

I don’t know the city. I don’t have friends here. Isolated like this for the first time in my life, I’m beginning to realize I don’t know myself either. Desire has burned through me, leaving me both empty and full of craving. I ask myself the question I hadn’t dared when she was still here: What does it mean that I fell for a girl?

It wasn’t the first time I’d considered that I might not be straight. But I grew up in China, where people didn’t talk openly about queerness. I wasn’t brave enough to claim that identity—at least, I didn’t think I was.

Coming out feels too big. My mind has too many moving parts I’ve never shared with friends because I can’t explain them, even today. I attended a women’s college, and I knew so many people who came out during that time. Still, it feels too late, too awkward and sticky to come out to them now after years of dating men.

“I keep practising, playing a stranger who’s confident in what she wants.”

So I don’t. Instead, I come out to strangers at socials, bars, restaurants. If they say something ignorant or hurtful, I can choose to never see them again. I don’t have that option with my friends and family back home.

I say the words out loud to see how they feel in my mouth. Dangerous. Good. Warm. It feels like acknowledging something I’ve wanted for a very long time, and then holding my breath to see if I’m going to be punished for it. It’s the same feeling as missing her.

Eventually, I summon the courage to attend a bisexual social. No one calls me out. I walk home giddy but also disappointed.

For several months I wait to be punished, to be called out; for someone else to tell me who I am so I don’t have to figure it out on my own. No one does.

I keep practising, playing a stranger who’s confident in what she wants. Someone who looks in the mirror and doesn’t feel guilty for wanting something she grew up being taught she can’t have.

Someone who knows who she is.

This isn’t a love story.

Falling for my friend forced me to confront myself. Coming out to strangers, again and again, is how I settle for the idea that only I can decide who I am.

A few months later, I stumble on these words:

“We want sexuality to be biological because we want sexuality to be instinctual and natural and out of our control, because choice isn’t nearly as romantic as surrender.”

The problem with making any choice is that it could be the wrong one.

When I last visited my grandmother in China, she berated me for wearing skinny jeans, not doing laundry by hand, cutting my hair short, saying I might not want kids. I imagine what she’d think if she knew how I’m living now; the choices I’m making because they’re what I want.

I cry about it, but the tears run dry after a while.

My whole life, I’ve splintered under the dull weight of my family’s disappointment. There’s a sharp pain that comes from not being accepted and it brings my blood to a boil. But it’s the same vivid colour as stepping into the light, introducing myself as I am, not as I was.

Coming back to Boston from China, I stand on the curb outside of Logan Airport, each breath clouding the winter air. A city full of strangers, away from the suffocating familiarity of home.

I don’t trust my identity. But strangers do.

To my new friends in Boston I’ve always been the outgoing, sensitive, weird n’ wild bisexual of our group—it’s who I’ve always wanted to be, even before I was brave enough to become me.

She and I still talk sometimes. It’s been almost a year since we last saw each other. I miss her. We’re still friends, after all.

And I’m still not completely out. In some way, I don’t think I’ll ever be. But I’m no longer a stranger to my own feelings.

I may not be whole, but I’m more than I used to be.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra