It was his eyes that got me. We would sit in my basement, glued to the TV as we duked it out on Super Smash Bros. He always picked Zelda as his character, but I was more likely to mix it up. He’d often win, and my heart fluttered every time my avatar would erupt in a geyser of light as it flew off the screen. I’m glad he’s winning, I’d think to myself. People like winning, and if he keeps winning then maybe, just maybe, he’ll like me too.

We had only been friends for a year, but in “High School Time” that was practically a lifelong brotherhood. Somewhere along the way, I had come out in the gayest way I could conceive—a melodramatic Instagram post.

I thanked my supporters and rebuked my haters (of which there were, thankfully, none). It made me the first boy in my Catholic, suburban high school to publicly declare his queerness. I had strategically timed my post (which featured—you guessed it—a tacky rainbow flag) during the summer vacation in the hopes that my classmates would move on to fresher gossip by the time September rolled around.

On the first day back to school, I was wound up so tightly I thought I might snap. I braced myself for the harassment and slurs and torment that had plagued my first decade of schooling. I was mercifully spared of any irregular attention, beyond a couple of hugs and some stilted congratulations for my “bravery.”

And just like that, everything was back to normal, or at least back to how it had always been. I may have been the only gay kid, but I was used to being different, and I had an incredibly supportive friend group by my side.

And of course, there was him.

He was always shrouded in darkness—he insisted on wearing only black clothing and remaining emotionally distant from our friends. Nobody ever seemed to know what was going on in his head, but his enigmatic personality made me all the more drawn to him.

One day, I arrived at our usual lunch spot. I immediately sensed that something about him, about his energy, was off. He was flanked by a couple of our closest friends, they were prodding him to tell me something. He hesitated. He looked up at me and uttered two words I never thought I’d hear another person say:

“I’m gay.”

I was taken aback. It never occurred to me that there were gay people other than myself. I’d always been programmed to think that queer people didn’t exist; I’d spent my short lifetime convincing myself that my identity wasn’t real. Even at that moment, after I had declared so forcefully and so publicly that I was gay and proud, I never entirely convinced myself that I was really gay, much less that there were others like me.

And yet, the evidence was before my very eyes in the form of a gawky boy clad head to toe in black clothing who had chosen me, me, to confess his darkest secret to.

Still in shock, I awkwardly muttered a hasty “okay” before sitting down, gingerly nibbling my sandwich and putting his confession out of my mind.

But that night, as I scanned produce at my minimum-wage cashier gig, my mind wandered to him and I caught myself wearing an impossibly wide grin.

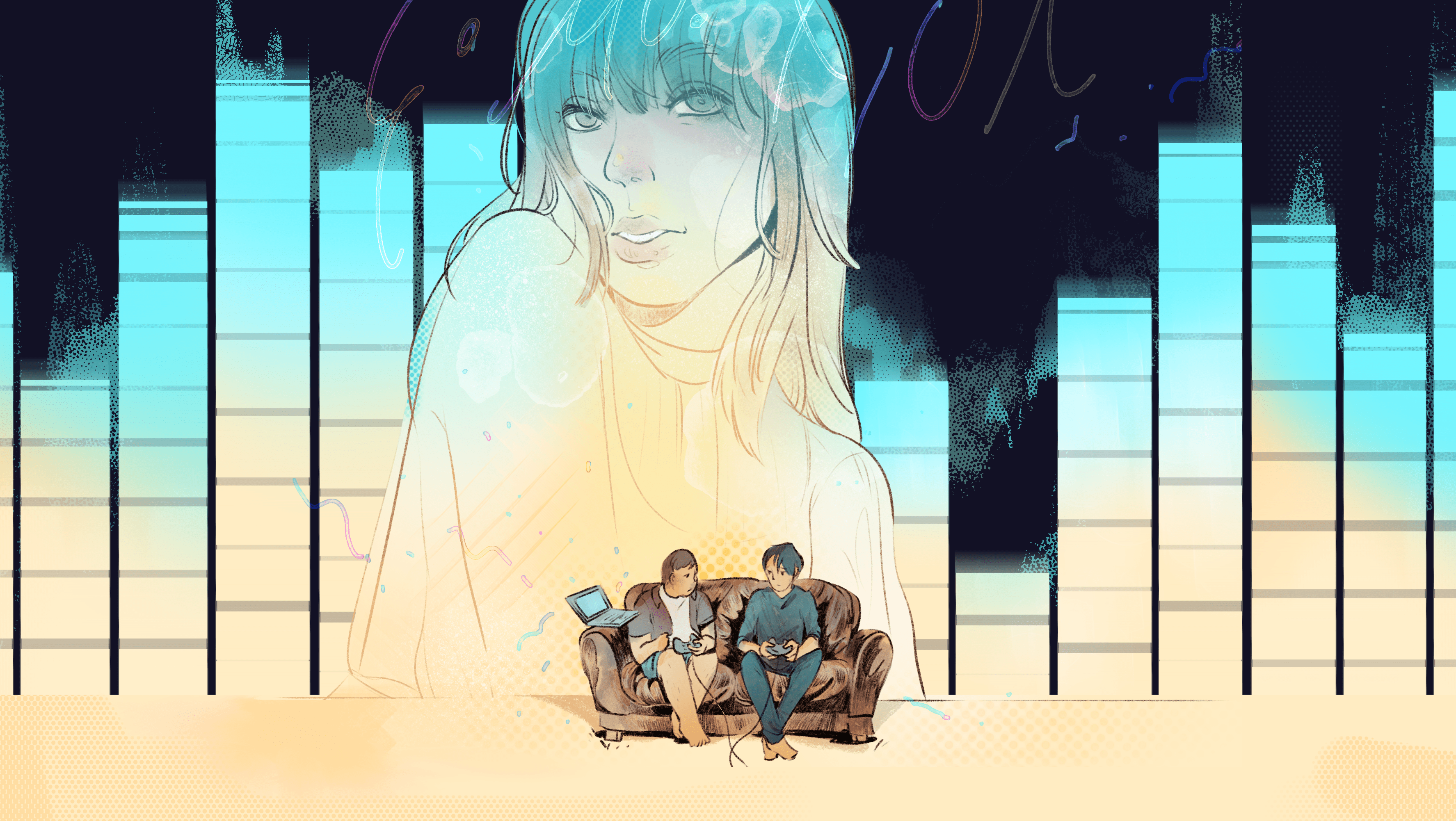

We soon started hanging out alone on a frequent basis. My suggestion, of course. He’d come over, and we’d slink down to my basement to innocently fry our brains for hours playing on my Wii. In between rounds of Super Smash Bros., we’d chat and go over the week’s hot topics: “She said WHAT?,” “He hooked up with WHO?”

We wouldn’t look at each other when we spoke—our eyes remained fixed on the glow of my TV. But with each gaming session, I sat slightly closer to him.

One day, after a particularly action-packed game of Super Smash Bros., I found myself locked in a euphoric daze. The scent of his deodorant lingered in the stale basement air, which sounds gross now but seemed really enchanting at the time. On a whim, I flicked open my laptop and played Carly Rae Jepsen’s Emotion on shuffle. At the time, it was being circulated on Tumblr as an underground pop diamond, and I thought I would give it a chance.

The cacophonous first bars of the lead single “I Really Like You” rang out of my laptop speakers and, instantly, I knew I was about to experience something powerful. I felt as if a gilded angel had burst from the clouds to bestow some great prophecy on me and the rest of humankind. Jepsen’s trademark silky vocals serenaded some unnamed object of desire backed by an ‘80s-era beat, beckoning me to dance as if nobody was watching. And since I was alone in my basement, I did.

When the chorus kicked in, it stopped my dance steps dead.

“I really really really really really really like you,” Jepsen cried. Each “really” seemed to catapult her desire impossibly further into the stratosphere. “And I want you / Do you want me? / Do you want me, too?”

My mind began to race. A million thoughts flooded my brain. Somewhere in the repetitious, breathless hook, I had a revelation.

I was in love.

I had never thought I was capable of romantic same-sex attraction. I snuffed out any spark that had previously made its way into my mind, dismissing it as unnatural, as something to be ashamed of, as a sin.

But in Carly Rae Jepsen’s lyrics, of all places, I found the validation that eluded me for the duration of my adolescence. The songs on Emotion—“I Really Like You” being the most obvious example—deal with ecstatic, obsessive, moderately juvenile and, most importantly, unrequited romantic attraction. It’s a work that deals with a singularly queer representation of romantic love.

“Somewhere in the repetitious, breathless hook, I had a revelation. I was in love.”

Of course, I had heard love songs before—the kind of gooey love songs peddled by the likes of Stevie Wonder and Céline Dion. But I never related to the content of those songs, because they typically described a love that was evident, viable and tangible.

As queer people, we are often deprived of the adolescence of our straight peers. It seems like they get to experiment romantically and sexually long before the rest of us, without fear of punishment or ridicule or shame.

As a result, we lead comparatively stunted romantic lives that, by the time we reach adulthood or even late adolescence, that lag behind our straight cohort. We’re left to unpack years of internalized homophobia before we can begin to process any semblance of authentic romantic attraction, much less a healthy romantic attraction.

But at that moment in my basement, with the bubblegum melancholy of Emotion playing in the background, I knew I had to do everything in my power to pursue this feeling until he was mine—and I had Carly Rae Jepsen, the High Priestess of Canadian Pop, as my companion.

I spent my days gazing at the clock, yearning for the minute hand to hit 11:30—lunchtime—so that I could dash out into the hallway and be with him (along with 15 of our closest friends).

I’d take every opportunity to gaze unblinkingly at him, drinking in his every word. I took fleeting mental snapshots: The way his thick hair fell impossibly suspended inches above his head, a tousled but measured shock of jet black; the way his face would slowly crack into a broad smile when I told a joke; the way his dark eyes bore unflinchingly into me when I spoke, respectfully attentive—unnerving in the best way.

As we grew closer and closer, our Smash Bros. talks grew increasingly intimate. Though we never tore our eyes away from the screen, we shared secrets no one else knew over the cartoonish sound effects of the video game.

He said he wanted to come out to his family, but that he was worried about how they might react. He told me his parents had said less than positive things about gay people in the past, and though he was frightened of the consequences, he desperately wanted them to know who he authentically was.

“We locked eyes, a rarity in my gaming den. Carly Rae’s words struck me like a lightning bolt.”

We sat adjacent to each other on my leather couch, my hips inches from his, electricity crackling in the small cavern between us. Although I had never so much as held someone’s hand, I resisted the urge to throw myself on him and confess my unending love. I thought of little else but his touch, his fingers spiralling around mine.

One day, as he pummeled me into oblivion on Smash, he told me that he had done it. That he had told his mom the truth.

He spent the night at a friend’s house after the confession, for reasons that still aren’t entirely clear to me. He remained mired in his usual coolness, but the tumult raging within him was evident. He had come out, but I think he knew that it was the beginning of a long, obstacle-ridden road.

I turned to him, and he turned to me. We locked eyes, a rarity in my gaming den. Carly Rae’s words struck me like a lightning bolt.

“Who gave you eyes like that? / Said you could keep them?”

He soon left my house for the last time. We never hung out much after that.

He became more aloof at school, made other friends and hung around less. We would spend time together in groups, but a cool wind occupied the space between us where I thought sparks had once flown.

Soon my heart froze over and I distanced myself from him. I grew cruel and petty. I decided to avoid him at school. At the time I felt justified—since he was avoiding me, I’d just cut him out.

“He became more aloof at school… a cool wind occupied the space between us where I thought sparks had once flown.”

His sudden change made me relive painful memories. It reminded me of the many years I spent friendless, mercilessly tormented for my femininity, my weight, my mannerisms. I was convinced that I was unworthy of love. I convinced myself that he, too, was just another person who would not love me, because gay people—especially chubby, awkward gay people like me—don’t get to be loved.

So I hardened against him. I transformed my affection for him into disdain. When he confronted me about my sudden change in attitude, I doubled down and wrongfully accused him of acting like he was above being my friend.

We didn’t speak for years.

When I got to university, I found that I was not alone. I made a small group of queer friends and racked up a number of whirlwind love affairs—some fiery and short-lived, others long and affectionate. Along the way, I found that, yes, I was capable of love and, yes, I was deserving of being loved, too.

Between my third and fourth year of university, I was jolted by a Facebook notification. First, I saw his name, then his message: “Hey man, how’s life been?”

I responded immediately, and before I knew it we had made plans to get sushi.

I was nervous as I pulled up to his apartment, unsure of what to expect. A thousand questions flashed through my mind. I wondered how the last few years had changed him. What would he look like? How had he changed? How had he remained the same? Would he still like me? Would I still like him? Would I really, really, really, really, really, really like him?

He exited his house and I nonchalantly looked away, pretending I was too cool to watch him walk to my car. As he approached, I noticed that he had changed. He looked older, stronger. Wiser. More composed.

He sat in the front seat of my car, and we began to chat—it was as if no time had passed. He had certainly matured—he was less performatively aloof—but everything I had always appreciated about his personality remained intact.

We got sushi and sat across from each other. We made real eye contact for the first time in three years. The eyes I had fallen for were before me once again, and a long-dormant, anxiety-ridden part of me rose up and beckoned for them.

But as quickly as it had come, the feeling dissipated. A peaceful warmth surged through me. My best friend was back, and the version of me who had killed our friendship had died long ago.

The words of Carly Rae Jepsen, as they often do, echoed in my brain.

“Before you came into my life / I missed you so bad.”

Five years ago, I never thought I could miss anything more than the dizzying romantic attraction I once felt for him. I now know that that was a manifestation of my own unquenchable self-loathing.

Looking back, I see my actions for what they truly were. I realize that I do not miss the toxic infatuation that soiled one of my greatest friendships—I simply longed for my friend and his company. I missed him.

I missed him so bad.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra