“You can’t tell where the head is and where the anus is and where the armpit is. You become conscious of the fact that humans leak fluid,” says Gillian McIntyre, describing Study for Portrait on Folding Bed (1963). Credit: Oil on canvas, Tate Britain, courtesy of the Estate of Francis Bacon/SODRAC 2013

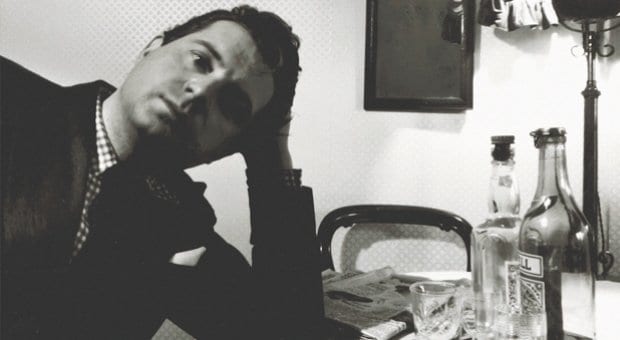

Police found Francis Bacon collapsed in an alley, badly beaten but still breathing. At the time, he was living in Tangier with his lover Peter Lacy. Bacon (the painter, not the philosopher) was an established artist by 1955, having already painted some of his most famous work.

The chief of police told the British counsel-general he would step up patrols.

In the following weeks, police repeatedly found Bacon bruised and passed out on the street. Eventually, the chief concluded that “Monsieur Bacon aime ça.” Indeed, Bacon enjoyed a good beating every now and then.

To use today’s language, Bacon was a sub. And his lover Lacy — tall, handsome, alcoholic, several years his junior — had a cruel streak. But Lacy was so volatile and so destructive that Bacon occasionally feared for his life. On at least one occasion, the threat seemed sufficiently imminent that Bacon charged out of his flat in nothing but a pair of fishnet stockings.

Bacon’s paintings are extreme: figures are contorted, howling, their skin is being peeled. He often painted the male body using a bruise palette of greys, purples and greens. One cannot be sure, in many cases, whether the figures are involved in consensual BDSM torture or the kind of non-consensual torture that so marred the 20th century.

It is no accident that the Art Gallery of Ontario’s new show, featuring Bacon’s work alongside that of sculptor Henry Moore, is subtitled Terror and Beauty.

While Bacon publicly drew a line between his personal and artistic life, he no doubt cultivated his bad-boy image. The same anecdotes pepper each of his major biographies: He spent his teen years as a hustler and rent dodger in London’s Soho district. He took older lovers. He wore too much makeup.

One such gem: Bacon’s father, exasperated by his son’s queerness, asked family friend Cecil Harcourt-Smith to straighten him out. Harcourt-Smith took the 16-year-old to Berlin. But rather than cure Bacon of his homosexuality, Harcourt-Smith fucked him mercilessly for a few days until he lost interest. The teen elected to stay in Berlin a while longer, turning tricks and stealing money in what was then the world’s premier city of sin.

After Harcourt-Smith, Bacon would continue to take father surrogates as his lovers until his early 40s, when he met Lacy in a dive bar in London’s West End. Out of hundreds of men, Lacy is often singled out as the love of his life — a tempestuous complement to Bacon’s masochism and dramatic flair.

Viewed in this light, pairing Bacon with the heterosexual, buttoned-down Moore is an odd choice, admits Gillian McIntyre, the visual interpreter of Terror and Beauty. And yet there are parallels.

“Bacon and Moore couldn’t be much more different. But when you see their work together, you see the shared themes of trauma and violence,” she says.

The exhibition starts with a timeline of the two artists’ lives, with important events of the 20th century spliced in. Seen in this way, it’s inevitable that they would have certain experiences in common.

“They were both in London for the Blitz. And they both saw all kinds of horror. World War II was the first really civilian modern war for the British. Bombs were dropping relentlessly on top of you,” McIntyre points out.

Unlike most of their contemporaries, both Bacon and Moore took as their subjects people, distorted as they may be, rather than abstract forms. In the post-war period, where pure colour blocks and geometric shapes were en vogue, Bacon and Moore were at odds with the prevailing tastes.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Bacon’s work elicited strong reactions — much of it sharply critical — from the art world. And it’s no wonder. Even today, he has the power to shock and surprise.

“Whatever came his way, he looked at it full in the face and painted it. Everything was grist for his mill,” McIntyre says.

Francis Bacon and Henry Moore: Terror and Beauty

Sat, April 5–Sun, July 20

Art Gallery of Ontario

317 Dundas St W

ago.net

Essential reading:

Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, Michael Peppiatt, 1996

The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon, Dan Farson, 1993

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra