Dr Aaron Blashill studied sexual orientation and steroid use in American teenage boys. Credit: Xtra staff

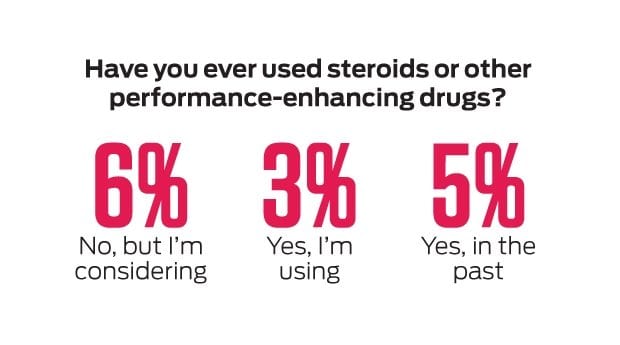

Via squirt.org, Xtra asked men who have sex with men if they use steroids. Credit: Xtra staff

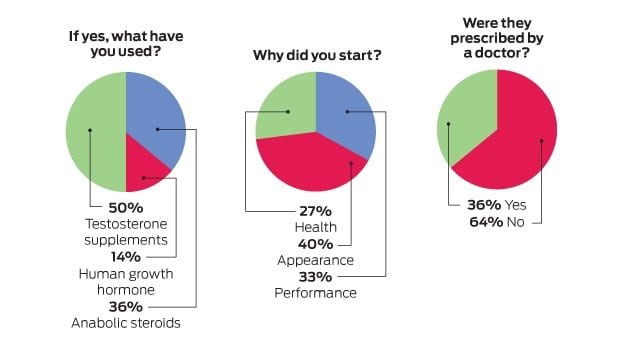

Via squirt.org, Xtra asked men who have sex with men if they use steroids and, if so, why and what they use. Credit: Xtra staff

When Dr Aaron Blashill, a researcher and clinician at Massachusetts General Hospital, first saw how many American gay teenaged boys were using steroids, he assumed he had made an error.

He guessed the number would be high, maybe as much as two or three times normal, but this, he thought, could not be correct.

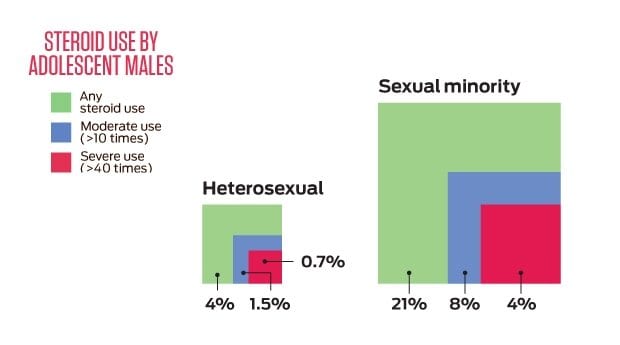

He went back and rechecked his analysis, then rechecked it again, and again. The numbers told him the same thing: out of a sample of 17,000 American teenagers, nearly six times as many gay and bisexual boys had used steroids as their straight counterparts.

When Blashill and a team of researchers at The Fenway Institute, an LGBT health research centre in Boston, published their work in February, they demonstrated a long suspected but little understood link between gay men and anabolic steroids. Only four percent of straight teenagers in the study said they had ever used steroids, but among gay and bisexual teens the rate shot up to 21 percent.

Gay and bisexual boys were also more likely to use steroids heavily: four percent said they had used more than 40 times, compared to only 0.7 percent among their straight peers.

The conclusion was clear. Gay teens are injecting themselves with anabolic steroids much more than any others, and that likely means that gay men are as well. Although we still don’t know how many adult gay men use steroids, most lifelong steroid use begins among young men in late adolescence and the early 20s.

Somewhere in the numbers lay the reason.

***

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are a family of hormones that include the natural male hormone testosterone and a broad family of synthetic relatives.

Steroids bind to hormone receptors in the body, causing both androgenic effects — male characteristics, such as body hair — and, more importantly, anabolic effects: muscle growth.

When a man ingests or injects artificial testosterone, the brain signals the pituitary gland to shut down production of natural testosterone and sperm, causing the testicles to shrink. At the same time, the rush of testosterone signals muscles to increase in size, and almost any intense exercise produces dramatic growth.

Steroids act just like testosterone but the effects are vastly multiplied: they quite literally make you more of a man.

***

For Cameron, a 20-year-old artisan from Ottawa, it all started when he got sick. (Xtra agreed not to use his last name for this story.)

Cameron was fit and healthy until a year of illness and school stress tore 40 pounds off his body. Standing five foot 10, at 118 pounds, he struggled to buy clothes, and his ribs showed through his chest.

That’s when he turned to his roommate’s boyfriend, a local steroid dealer. He liked the man’s confident professionalism and was comforted that his years of steroid use seemed to have had no consequences. On top of that, the drugs were delivered right to his door, along with clean needles and personalized advice. He didn’t have to worry about anything.

“I just wanted to get back to normal,” he says.

Cameron started on pills, 12 to 14 a day of the common synthetic steroid methandrostenolone, the street name for which is “d-bol.” He was afraid of needles, he says. Oral d-bol was hell on his liver, though, and after too many rough hangovers, he switched to a cocktail of injectable testosterone, a few d-bol pills and another injectable called Nolvadex that prevents the growth of breast tissue associated with steroid use.

Cameron doesn’t know much about what all the drugs do or how they work. He trusts his dealer for that. His drugs came in pill bottles and 10 millilitre vials, and he took them as directed.

And they worked. Within two and a half months, Cameron says, he was back up to his normal weight. He grew in a thick beard and new hair on his chest where the old had been lasered off. He felt more aggressive, and his friends noticed he was more intense, more serious and smiled less often. But he also had the body and the muscles he wanted.

While Cameron started injecting steroids to get back to his normal weight, they are now a regular part of his routine. He takes one or two cycles of drugs a year, often topping out at a lean 185 pounds, 15 pounds heavier than his original weight.

Steroids are a balancing act, he says; holding on to the ideal steroid body too long has consequences. Last year, he ran one cycle too long and found himself breaking out in acne and feeling sick, exhausted and hormonal.

“My advice is to remember that it’s temporary,” he says. “It’s going to be up; it’s going to be down.”

***

According to the traditional story, steroids and the hypermuscular gay image appeared in the 1980s as a reaction to HIV.

In the 1970s, masculinity meant a very different thing. Skinny men wore mustaches and athletic socks in gay porn. The Village People advertised for new band members with an ad that read “Macho types wanted” and scored a cowboy and an Indian with narrow jawlines and slender biceps.

Then, in 1981, two things happened almost simultaneously: first, a new disease, initially called “gay-related immune deficiency,” was identified in North America; second, an American bodybuilder named Dan Duchaine published The Underground Steroid Handbook and brought practical knowledge about anabolic steroids out of the elite world of sports and made it available to everyone.

Steroids had been used experimentally by athletes as early as the 1930s, but in the 1980s, steroid-fuelled bodies were suddenly everywhere: on television, in magazines, on action figures and in porn.

The synchronicity of these two events became immediately meaningful for gay men. In an attempt to avoid the stigma of muscle wasting associated with HIV, they eagerly took steroids to show their muscularity, and thereby their health. From this, gay men’s affinity for steroids was born.

At least that was the story until now. We don’t know very much about how steroids affected the HIV-epidemic generation — now in their late 40s, 50s and 60s — and until someone conducts a survey like Blashill’s on men over 50, the link between HIV and steroids is no better than educated speculation.

Either way, the HIV story probably does not apply to the teens in Blashill’s study. The teenagers of today were not even alive during the plague years of the HIV epidemic and likely have never been exposed to the fear of wasting and thinness that pervaded the 1980s and ’90s. So why are they so eager to bulk up?

***

For David Brennan, a professor of social work at the University of Toronto, Blashill’s results make sense. In 2008, he asked 380 gay men at Toronto Pride about body image and behaviour, and the results illuminated a web of factors that help to explain the Fenway study.

Gay men, he discovered, were more likely than straight men to suffer from eating disorders and to be dissatisfied with their bodies. Eating disorders, in turn, were associated with depression, anxiety, internalized homophobia, substance abuse and the desire to gain muscle.

All the pressure of bullying, homophobia, an image-conscious gay culture and the constant questioning of their identities as men, Brennan found, wears at gay men’s self-esteem and builds a desire for muscular, masculine bodies. This stress, he thinks, may be driving them to testosterone.

“Over the last couple of decades, the pressure on young men to fit in and have a certain kind of body is just growing exponentially,” he says.

Brennan believes gay men are particularly likely to choose testosterone because they feel pressure from both sides. On one side, a majority heterosexual culture pushes gay men to fit in and project a masculine image to avoid negative stereotypes of effeminacy and weakness. It is telling, he thinks, that gay men who feel worse about being gay are more likely to want to be muscular.

On the other, gay men must fit into a gay culture where manliness is a valuable commodity. Photo-centred dating and hook-up apps make a good-looking body even more important. Since the appearance of steroids, men in gay porn and media have followed the trend of hulking muscularity. A mustache and leather chaps are no longer enough for a man to be a man; he needs pecs.

“Just look at the imagery,” Brennan says. “Look at any ad. Look at any website or profile pic. What are people drawn to? What do the models look like in the ads in Xtra? That’s really powerful stuff.”

Sure enough, when Blashill took a closer look at his numbers, they showed pressures similar to those identified by Brennan.

Blashill tracked how likely the teenagers in his study were to feel unsafe or victimized, use other drugs or suffer from depression. Not only did he find that gay and bisexual teenagers scored higher on each of these metrics, but each was also associated with higher use of anabolic steroids.

In other words, a substantial part of gay teens’ steroid use was not directly related to being gay. Instead, the teens were feeling depressed and anxious because of the strain of being a sexual minority. As a countermeasure, they were taking steroids.

Even when Blashill controlled for all these external pressures, however, gay teens were still more likely than straight teens to use steroids. What was the missing factor? Like Brennan, Blashill thinks it is body image.

It would be easy to imagine that under these conditions, older gay men would turn to image-enhancing drugs to keep up with the younger crowd. In this respect, however, Brennan’s research offers a ray of hope.

His survey showed that gay men actually become progressively less likely to suffer from disordered eating and poor body image as they grow older. Instead of comparing themselves to the younger generation, Brennan says, older gay men seem to be getting comfortable with their aging bodies, muscle loss and all.

***

Cameron is now 25 and still uses steroids. He likes them and has no intention of quitting. If he could afford to add higher-end, more expensive products to his regimen, he says, he would.

“I don’t know how long I’ll do it,” he says. “As long as I have the money to afford it. I don’t have any problem stopping.”

A few of Cameron’s friends roll their eyes when they hear he uses steroids, but most shrug it away. In fact, he says, since he’s started using, he notices more and more of the tell-tale signs of use in other men, gay and straight — not just the huge arms and bowling-ball shoulders, but the perfect hair and masculine swagger of men who care how they look. It’s all part of the steroid life, he says.

“I do like my look when I’m on them, but I realize that it’s just vanity,” he says. “It’s no different than getting my hair dyed. It’s just what it is. If you want to live that life and you’re vain, then go for it. If you don’t, then you don’t have to.”

***

Perhaps the greatest irony of gay men’s dalliance with steroids is that one of the first uses of synthetic testosterone was the medical treatment of homosexuality.

As early as the 1920s, Viennese urologist Robert Lichtenstern was implanting pieces of human testicle into gay men in an attempt to cure them.

Despite the obvious failure of the testosterone cure, the theory persisted into the 1940s, when it was at least partly put to rest by Alfred Kinsey. It became apparent, after a number of court-ordered testosterone treatments for gay men, that the injections were only making gay libidos stronger.

If Blashill and Brennan are right, however, steroid use among gay men continues to have everything to do with manliness. Between two cultures that both reward macho, the lure of masculinity in a syringe is obvious.

Next in Xtra’s series on steroids: are they really as dangerous as we were once told?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra