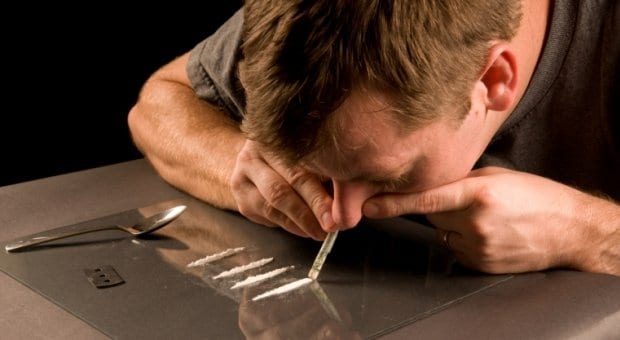

The risk of cross-contamination from injection drugs is not news to anyone, but the results of a UCLA study suggest that there is reason to reject the rolled-up dollar bills and reconsider the power of powder.

A recent scientific study reveals that there is a correlation between cocaine use and an increased susceptibility to contracting HIV. According to the UCLA AIDS Institute, the dormant CD4 T-cells that provide the human body with immunity to HIV are destroyed upon exposure to cocaine. What makes this even more problematic is that the eradication of these cells allows for increased production of the virus in cases where HIV is already present.

However, this news about blow isn’t blowing the minds of people in the HIV community. Dan Allman, a professor in the HIV Social, Behavioural and Epidemiological Studies Unit of University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, says that the connection between drugs and HIV extends beyond their physical effects on the body.

“If that relationship had been acknowledged, the rates wouldn’t be where they are,” Allman says. “I know I’m not supposed to eat candy bars, but come Halloween, it happens.”

While this study exposes another drug as an enemy in the battle against HIV, Allman says that influences like sleep, stress and other environmental factors are of equal importance to the immune system.

It seems that although drug use will always be a significant element to consider in HIV prevention, medical revelations are not yet substantial enough to deter people from indulging in their drug of choice.

“Cocaine and any number of substances have cultural practices related to sharing, intimacy and traditions. Science can change knowledge, but it can’t change the meanings of these traditions,” Allman says.

The AIDS Committee of Toronto runs a harm-reduction support group called Spunk, which is a safe space for queer men to discuss substance use. Ryan Lisk, the program’s facilitator, says that although new findings related to drugs are important to consider, scare tactics and health warnings have yet to curb behaviour.

“Studies do help to inform the way we develop the program’s education and advocacy pieces,” Lisk says, “but the goals of Spunk are based on the community’s needs, not research.”

He has found that the connections between substance abuse and HIV make it harder for people to access support. Not everyone sees drug use as problematic, so programs should encourage safety, as the use of substances does not necessarily mean the same as the misuse of substances.

Toronto Public Health’s 2012 report titled Communicable Diseases in Toronto revealed that four percent of the total 497 people who were diagnosed with HIV in 2012 contracted the disease from illicit drug use. While UCLA’s study highlights cocaine because of its effects on T-cells, HIV is not frequently spread this way in Toronto.

Spencer, 59, a former drug user who is HIV-positive and prefers not to use his full name, was not aware of cocaine’s scientific relationship to HIV, but he is not surprised by the study’s findings. “There isn’t a drug in the world without a side effect,” he says.

Spencer knows several HIV-positive people with drug addictions but doesn’t think a study like this one will make them think twice before their next hit. He says that some people in the HIV-positive community are looking for something to enhance their mood, and because of their diagnosis, the means with which they achieve that enhancement can be irresponsible.

“At the beginning, I thought I was dying,” Spencer says. “But you realize you’re not going to die tomorrow and you take life into your own hands.”

Spencer believes that drugs are so accepted in the party scene that adhering to medical cautions will not outweigh the opportunity for a good time within any of the social groups he has been a part of.

According to Allman, people working in HIV prevention face the challenge of creating messages that permeate the instant benefit of drug use. “This behaviour reflects carpe diem. It is not new or specific to HIV or HIV-positive individuals,” he says. “As social animals we seize the day. We do what we can to get by.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra