I hear “voices”

My identity shifts and changes

Like the wind

Deep in my heart

I know I am

Demons flying like vampire bats

From my mind

Demanding everything Of me

My name is

Pain

Anguish

Despair

Suffering

Torment

My demons live inside me

Everyday, everywhere

I could change my name

I’d rather change my mind

My name is mental illness Sharon

-from “Voices” by Sharon Taylor, excerpt from Deep System

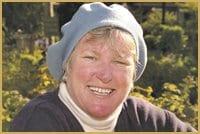

Vancouver poet Sharon Taylor writes about the anguish of suffering from mental illness for more than half her life in her first book of poetry, Deep System.

Through her writing, the 52-year-old English-born lesbian hopes to help dispel some of the widespread misconceptions about people with psychiatric disorders, and share the loneliness of being ostracized within one’s own community.

“By reading my book, people find out what I’m all about,” says Taylor. “My affinity for nature, grieving the loss of friends, about some of my more horrific experiences in the mental health system and how I dealt with it by writing powerful survivor poems.”

Taylor has suffered many losses during her life: her father (“that was like losing my best friend. We did everything together”); her younger brother Gary; numerous friends have committed suicide; and she’s lost countless jobs due to mental health issues.

“I wrote several poems about Gary to deal with my feelings,” says Taylor. “When my Mom got the book and read the poems about him, she just started to cry. Quite a few people start to cry when they read poems about him, but I found it very therapeutic to deal with his death by writing.”

Taylor, who also paints and does photography, started writing seriously in her early 20s-mostly poetry and keeping journals. It was around this time that she also became “visibly ill” and had to be hospitalized for the first of many times.

“I don’t tell people my diagnosis. If they ask me my diagnosis, I just say, ‘Sharon.’

“I feel like I’m growing beyond my diagnosis,” she says. “A lot of people don’t understand mental illness. People have a tendency to pigeonhole or else they get very afraid, so I don’t tell people my diagnosis unless I know them really well. So, it’s Sharon.”

Although Taylor addresses her psychiatric hospitalizations in her book, she refuses to discuss details during our interview. However, she does offer, “I had very negative experiences. I didn’t get proper treatment and that affected the way my life went for a lot of years. It was concentration camp-like treatment…

“I’m still dealing on a daily basis with what happened to me in there,” she continues. “Treatments were forced on me. I don’t think that’s any way to treat a person. Animals get treated better.”

Most of Taylor’s poems were written “during, after and in-between” hospitalizations-she writes about her bitterness toward the health care system, her disappointment in people, and her struggle with trying to remain stable.

“I don’t mind a small amount of medication. It keeps me stable and keeps me out in the community. If it wasn’t for my medication, I’d probably be in a hospital.

“People don’t understand that. Some people get very judgmental if you take medication. Some people even think that there’s no such thing as mental illness. All I can say to that is wait ’til it happens to you. You find out pretty quick that there is such a thing as mental distress or mental illness.”

Taylor draws her support from psychiatric nurses, her trauma counsellor, mental health workers, some friends and her mother.

Coming to terms with having a mental illness paralleled Taylor’s process of coping with her sexuality.

“Coming out was very rough because I was really not well. My emotional health was not very good. At points, I wasn’t well received by the gay community.

“People didn’t understand about my mental health issues. I just ran into some people that weren’t very understanding. I would have done better to run into more understanding women. That was very rough. It was traumatic, actually.

“I’m more involved in the larger community. I’m not so much involved with the gay community. I suffer from anxiety a bit and quite a few women don’t know how to deal with that, or they’re a bit afraid, so they have a tendency to back off.”

What does Taylor hope readers will learn about mental health issues from reading her book?

“Don’t be afraid. Educate yourself. People are more likely to harm themselves than they are to harm other people. Some people are afraid because they think you’re going to hurt them.

“There’s not enough education out there about people with mental health issues,” she says. “People’s symptoms are usually so frightening, they are more afraid for themselves than hurting someone else. Don’t be afraid to include the person in your activities.”

Taylor feels part of the lack of education and support for people with mental health issues is a direct result of the BC Liberal government cutbacks.

“It’s a war on poor women and anyone who is poor. It’s a war on people with disabilities. They’ve made a lot of cutbacks. I think the government is out for its own rich self. They don’t care about poor people. We really have to help each other out because nobody else is going to help us out.”

Taylor practises what she preaches. She does a lot of volunteer work with seniors, an environmental agency, and persons with mental illnesses. For pleasure, Taylor loves people-watching in coffee shops, renting movies, spending time in the Mole Hill Garden, writing on a bench in Nelson Park, and being on the seawall where nature and water provide tranquility and inspiration.

“The last part of the book is the nature section which is really upbeat and healing. I found a lot of healing in nature.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra