I’m shocked the first time I peruse the brochure for the Cedars, a campground for gay men and lesbians. It features a series of photos of a young, tanned, good-looking kid diving backwards into a pool. I recognize the grinning face immediately – Matt Dayler, a friend I haven’t seen since high school.

Matt and I came out together in Hamilton. We shared a lot of firsts – first time in a gay bar, first time cruising public spaces. Hell, we came out to our parents on the same night when we were 16.

It turns out he’s a Cedars regular. My first camping trip in years just got more intriguing.

I was always an outdoorsy kid with summer spent at camp. Later, I was a tripper, leading packs of kids on canoe trips through the wilds of Algonquin and Temagami and Kilarney for weeks at a time.

But as much as I loved camping, it always remained isolated from my life as a gay boy. The two worlds seemed impossibly far apart. Yes, there were furtive gropings in tents when I was 12 and 13; we called it “corn-holing” then, and it was never discussed openly as anything other than a hilarious joke.

I’m 26 now; time for camping and gay life to collide.

The Cedars is easy to miss. We drive down a long dirt road, passing the odd country store and farmhouse. The entrance is marked by two bright orange bins with no obvious purpose, and the number 1039, painted ominously on a piece of driftwood.

Oddly enough, the place is not very far from civilization. As we pass through the gate, I realize we’re disturbingly close to my parents’ home in Hamilton – less than 10 minutes, in fact. It’s as if there were rugged gay men camping out in my own backyard the whole time I was growing up, and I somehow never noticed.

We pay $45 for a long-weekend pass, and drive in. The Cedars is not exactly picturesque, but it has a certain charm. We pass a pool on our right, as well as a restaurant (where they serve breakfast all day and fries with everything). A huge, rustic-looking barn looms just beyond the restaurant. Soon, we’re traveling down trailer-lined roads with names like Fern Gully and Sleepy Hollow.

I’ve come with my boyfriend, Paul. We pitch our tent in a field near a cluster of well-cared-for trailers. Paul does everything he can to make our accommodations comfortable, but heavy rainfall has turned the earth to mud, and we will surely hear the muck squelching underneath us tonight as we fuck and sleep.

Sitting beside our tent, we can hear cars pulling into the campsite, one after another, filled with boys and girls ready to party the long weekend away. As in the rest of the world, status is determined by what you’ve got. It’s the specifics that set the Cedars apart. Who’s got their own golf cart? Who’s got a terraced garden? Is your front porch enclosed or open? Picket fence? Hot water? These are the Cedars equivalents of designer clothing, BMWs and gym tits (though gym tits are popular here, too).

Immediately we get high. It’s tradition. The campsite’s motto used to be “Welcome to the Cedars. Have another.” And another. And another. People here know how to drink, and I, for one, will be hard-pressed to remain sober this weekend.

“You find a different kind of fag here,” says one trailer owner, a gruff man called Bob. “And you don’t see many of them downtown.” Most Cedars patrons don’t live in Toronto – they live in Hamilton or St Catharines or Windsor.

The campground is a place where small-town gays and lesbians can come together and find community. It’s a ghetto, of sorts, but a very different ghetto, full of birdhouses and driftwood and mosquito netting. When people talk about “getting wood” at the Cedars, they really are talking about getting wood.

Everyone here knows each other. There is no electricity or running water, so people have to adapt. Generators and solar power are common, and some trailers even run off car batteries. As a result, the campground is not laid out in a typical grid pattern. Instead, the layout is random and chaotic, full of pathways and nooks and crannies. It’s easy to get lost.

When I told my dad I was coming to the Cedars for the weekend, he asked innocently if it was a nudist resort (which are common in the area). I laughed and told him it wasn’t. It’s true. Nudity is prohibited and the rule is enforced. One man tells me that the rule extends to lesbians going topless. It may be legal across the province, but it would be frowned upon here. “After all,” says the man, sipping his beer, “this is a place for families.”

I see several lesbian couples accompanied by children during my stay. Couplehood does seem to be the natural state here. Love stories abound. “People meet at the Cedars, fall in love and before you know it, they’ve amalgamated their two trailers into one big trailer,” says Bob. When amalgamation happens, it’s like the Ferdinands marrying the Borshtvorts – the creation of a trailer park dynasty.

But the Cedars isn’t just about love and family. It’s about sex, too. The promise of sex is omnipresent. You can almost taste it. At night, the campground sometimes resembles a huge outdoor bathhouse. Bob tells me of Fuck-Me Forest, a wooded enclave just beyond the trailers where men go at night to cruise. He says “seasonals” (men who maintain year-round trailers) won’t be caught dead there. But the forest is full of “tenters” on most nights. “Besides,” says Bob, “all the hot guys are tenters.”

Night falls; we are very drunk. The pulsing beat of house music creeps out across the campground like the hand of death in the Ten Commandments. We stumble through the darkness, following the beat to its source, an imposing barn near the pool.

I’ve been looking forward to a barn dance all day. I pictured a long, sweaty night spent dancing on the earthen floor of a rustic barn. There would be a tractor in the corner, rusting away, and a hayloft to serve as a backroom. Everyone would wear flannel shirts and dirty jeans, and we would stare up at the stars through a hole in the dilapidated roof.

Sadly, my butch fantasy is not to be. The barn at the Cedars is almost exactly like the Barn in Toronto. Picturesque on the outside, big gay disco on the inside. Walks like Tarzan, talks like Jane.

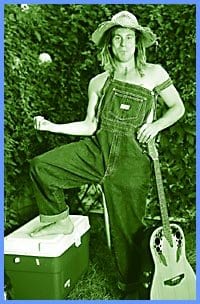

Once inside, we settle at the bar to do green jello shots. Soon we’re dancing. And then, like he walked out of an episode of Queer As Folk, I see him. Matt Dayler is dancing up a storm in the middle of the barn. He’s shirtless, and it seems as though everyone in the place is watching him. I walk over to him and he says, “Hey, how are ya?” as though we’d spent the whole day together.

Sometimes when you see someone with whom you share a history, it seems as though no time has passed. That’s how it is with Matt.

Our friendship was intimate, but never romantic. Matt was into older guys – much older guys. As for me, well… it just never happened between us. I remember making out with Matt furiously one drunken night, but we were just trying to impress and horrify our straight friends – mostly.

Matt introduces me to Freddy, his boyfriend of eight years, or, as Matt puts it, “My Daddy.” Freddy is a genial guy in his late 50s, with a white beard and a belly and a generous smile. He resembles a blue collar Santa Claus. He once operated Club 121, the Hamilton gay bar where Matt and I came out.

Freddy is a sweet guy, but I have to admit that it’s tough for me to understand his and Matt’s relationship. I notice the large tattoo on Matt’s upper right shoulder – a big older bear, naked, with a fat cock hanging between his legs. Dildos sprout all around him. Underneath, a single word is inscribed: “Daddy.”

It’s not that I’m a prude. But I grew up with Matt. We survived high school by relying upon each other. Fuck, we were each others’ prom date – a scandal that rocked Westdale High. As we dance and drink the night away, I can’t help staring at my old friend and wondering what brought him to this place.

After the barn dance, my boyfriend and I build a campfire outside our tent. Campfires never stand still. Sparks dance off the wood and sail into the night sky until they are indistinguishable from the stars. The pungent smell of burning wood makes me at once hungry and horny. The front of my body is burning hot; my back is ice cold. The light plays across the faces of my friends sitting around the fire

In the city, we gather around the television set. I’ll take a campfire any day.

The Cedars was once a horse stables. There is less than six feet of soil over the bedrock. The land, therefore, is not suited to building or agriculture. So it was used as grazing pastures. It was owned by a straight couple, George and Zada. Legend has it that a lesbian camped out on the grounds one night, and suggested to the owners that they open a campground for gay men and lesbians. And so the Cedars was born.

George died years ago, but Zada remains. She lives in a large house near the front gates, like the matriarch of a southern plantation, emerging once in a while to mix with the slaves. And she is, in fact, a Southern Belle, complete with drawl, gowns and rumoured facelifts. People tell me she hosted her own television show in Florida in the 1960s, called Fashion Chat, or something like that. She’s well-loved.

Pual and I spend Saturday poolside, soaking up the sun. It’s been a rainy year so far, and the pool is packed with seasonals taking advantage of the hot, sunny weather. Rock music blasts out of speakers at the poolside bar. This would be great, except that every time the bartender uses the blender, it brutally disrupts the radio signal. And being a pool bar serving a gay crowd on a hot summer’s day, the blender is in constant use.

Matt is already there when we arrive; he’s like the campground mascot. He’s lying in the sun singing along to the radio (“I’m a joker, I’m a smoker, I’m a… BBBRRR”). He introduces me to his “sisters,” among them is a local legend known as Squaw Billy (a name he’s gone by for 15 years).

Squaw Billy is a wiry Native Canadian with long, wild hair who lives at the campsite during the summer. He was taken in by George and Zada many years ago when the campground opened, and has been there ever since. He proudly tell me, “I helped buld this place with by bare hands.”

Billy is a constant source of amusement, but one gets the sense that people don’t laugh at him; rather, they laugh with him, at his crazy, tragic life stories. Squaw Billy is notorious for hitting on everyone he meets, including (rumour has it) the local foliage.

The seasonals will tell all kinds of stories about Billy, buth they are very protective of him. If you make fun of Squaw Billy, it’s as if you’re making fun of the Cedars, itself.

If Matt Dayler is the Cedars mascot, then Squaw Billy is the Cedars Patron Saint.

Another night, another barn dance. This time, a tenter slips me a tiny yellow pill – ecstasy. I’ve never tried it before, but tonight it feels right. Ecstasy is the drug of choice around here, though I’m told Special K and Crystal are popular too. Drugs are strictly prohibited at the Cedars.

At first, I feel nothing. I wonder what all the fuss is about.

Slowly, I begin to feel a buzz. Suddenly, it all happens at once. My loins are on fire. It’s like I’m on the verge of cumming in my pants, though I couldn’t get hard if I wanted to. I’m dancing like crazy, but I walk like I’m wearing cement shoes.

I look up at the ceiling, and for a moment I can see the stars through the dilapidated barn roof. But they’re gone almost as soon as I see them.

The ecstasy high reaches a tableau. We leave the barn dance only to discover one last Cedars ritual. Late at night, people congregate around a bonfire at a random location. How anyone finds the bonfire in the maze of trailers and dark pathways remains a mystery. Somehow, word gets around. The bonfire brings friends and strangers together to talk, drink, make friends and sometimes more.

We stumble across tonight’s fire, glad for its warmth.

Matt is here, sitting on a log by himself. He’s drunk. I don’t think he’s slept since we arrived at the camp. He doesn’t say much, but I can tell he’s happy to see us. I spot Freddy standing off to the side, watching over Matt from a distance.

Suddenly, I understand what their relationship is all about. Matt lives entirely in the moment. He doesn’t concern himself with the past or the future. He’s still a boy at heart, a boy whose life is governed by a sometimes reckless need for adventure. I guess he needs somebody older and wiser to watch out for him. I used to do that for Matt in high school. Now he’s got Freddy. And I’m glad.

As I look around the bonfire, I’m struck by the variety of people. There are men and women, young and old, working class and yuppies, each with their own unique sense of style. I spot leathermen, men with no teeth, fat and skinny and muscled, dykes wearing flannel and men in pajamas. Boots and sandals. I meet steelworkers and farmers and a lone orthodontist. Never in a million years would you see a crowd this diverse in any Toronto gay bar. Never.

When I was young, I hoped that gay life meant freedom to be who I really am. But that’s not what I found in the ghetto. The freedom promised by gay city life is often nothing more than an illusion – it has all the substance of a bump of K.

It seems to me, at this moment, sitting around a campfire with 50 strangers, that these men and women have discovered what many of us city folk have missed all together: true freedom. Not just the freedom to be gay, but the freedom to live as distinct individuals within a tight-knit community. Now that’s something to be proud of.

Sunday morning we pack our things. It’s time to go. Along the way to the gate we pass a group of lesbians dancing in a circle with their arms around each other, singing “We Are Family” at the top of their lungs. They are wearing 3-D glasses.

We pass the pool. Techno thumping. It’s almost noon. I spot Matt. He still hasn’t slept. I wave good-bye, but he doesn’t see me. He’s too busy dancing along the edge of the pool, somehow never falling in.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra