We were so young.

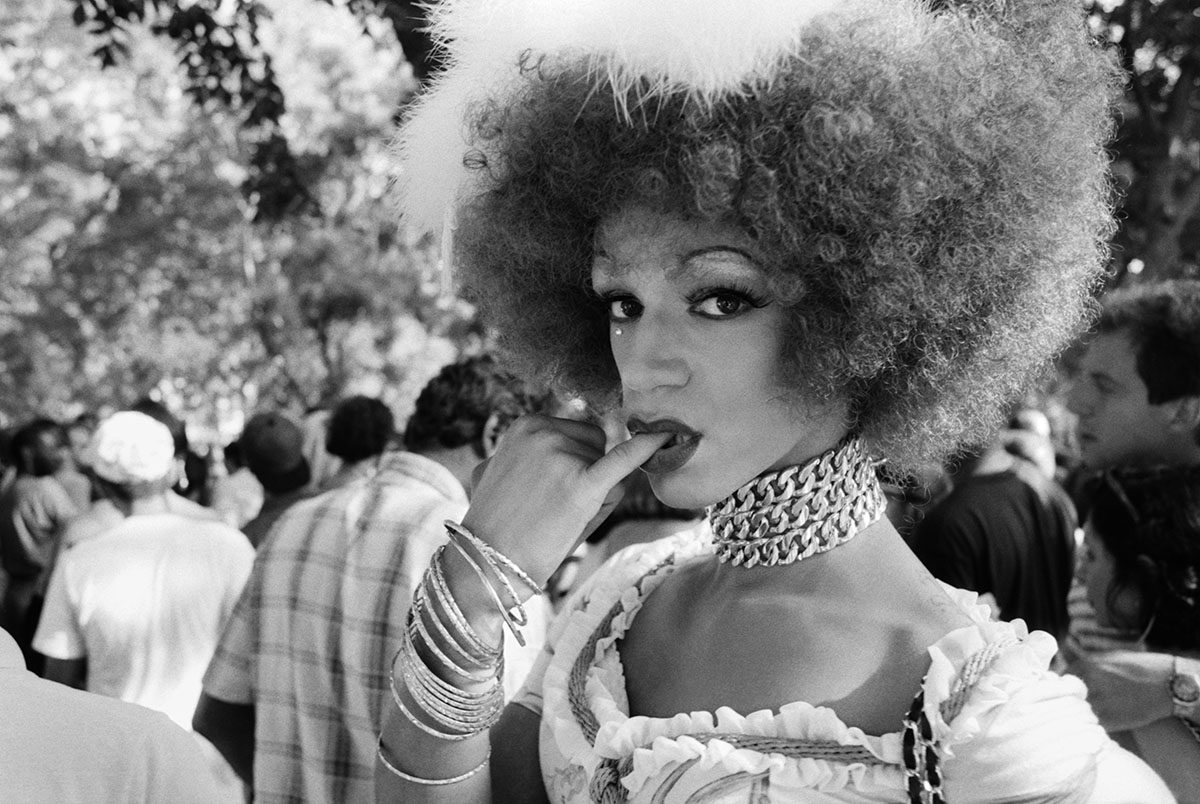

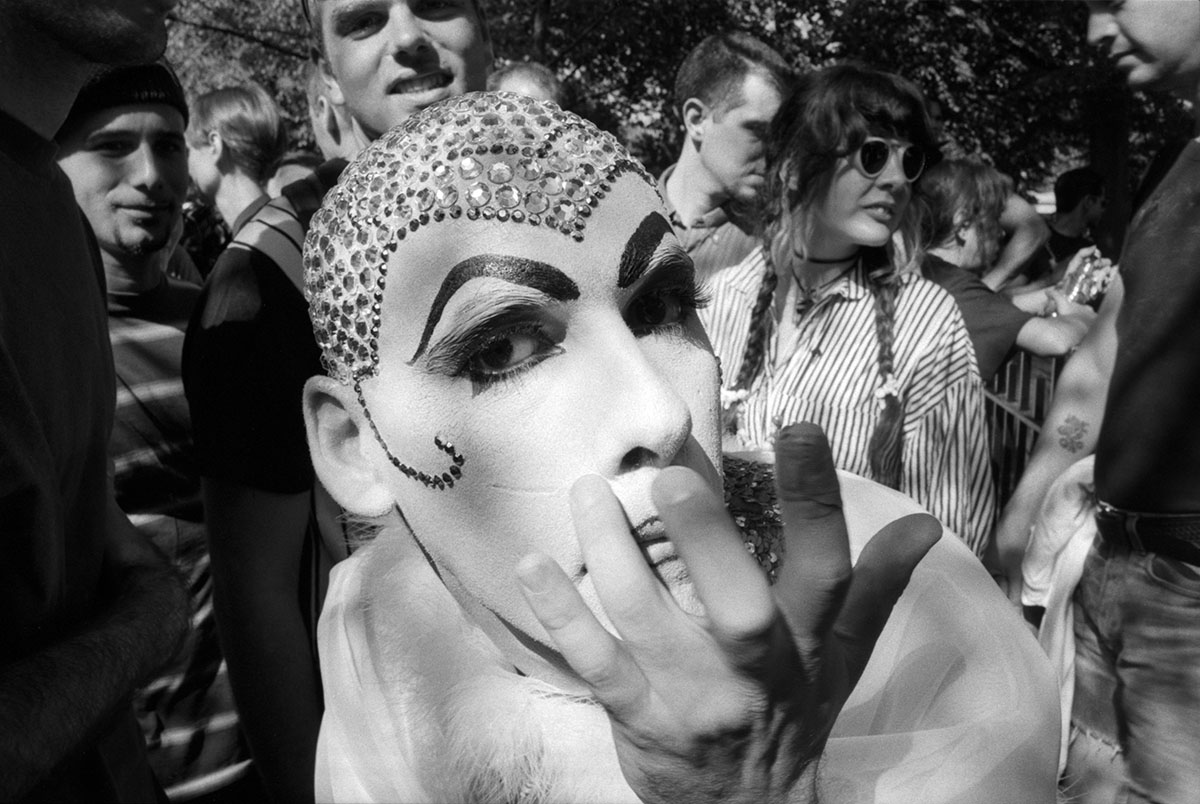

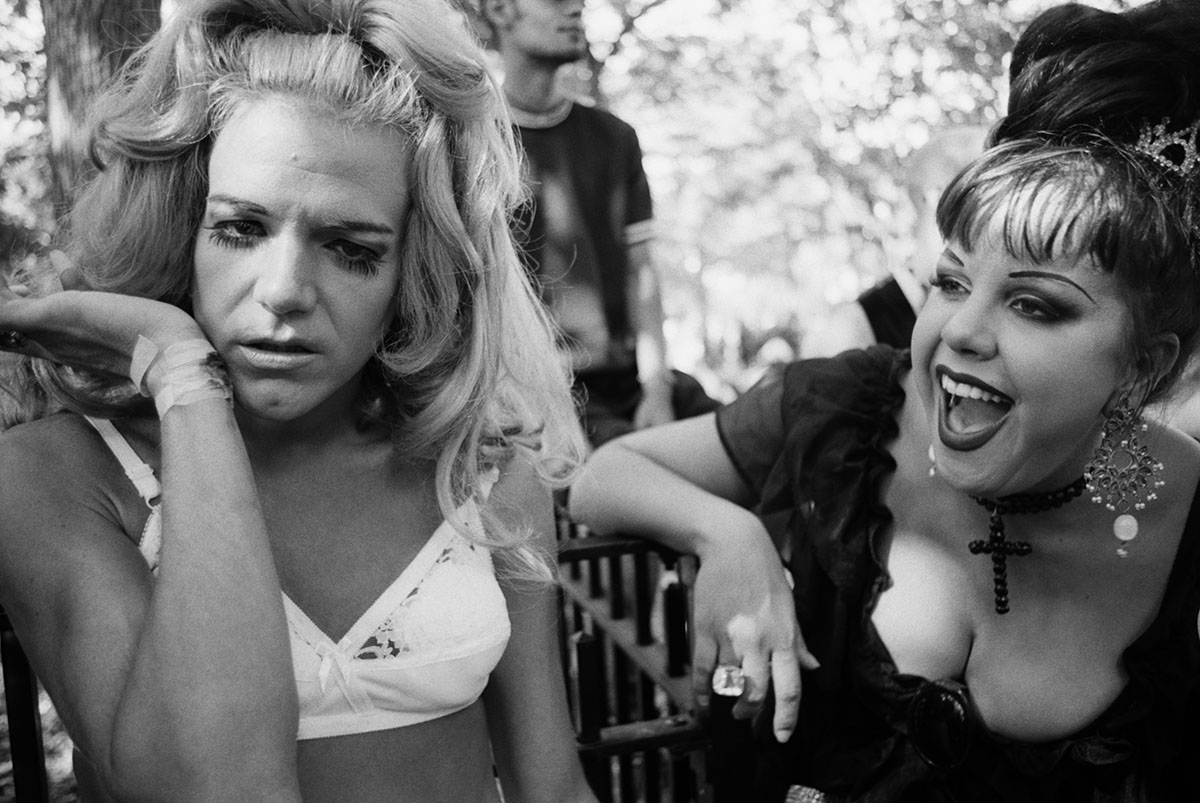

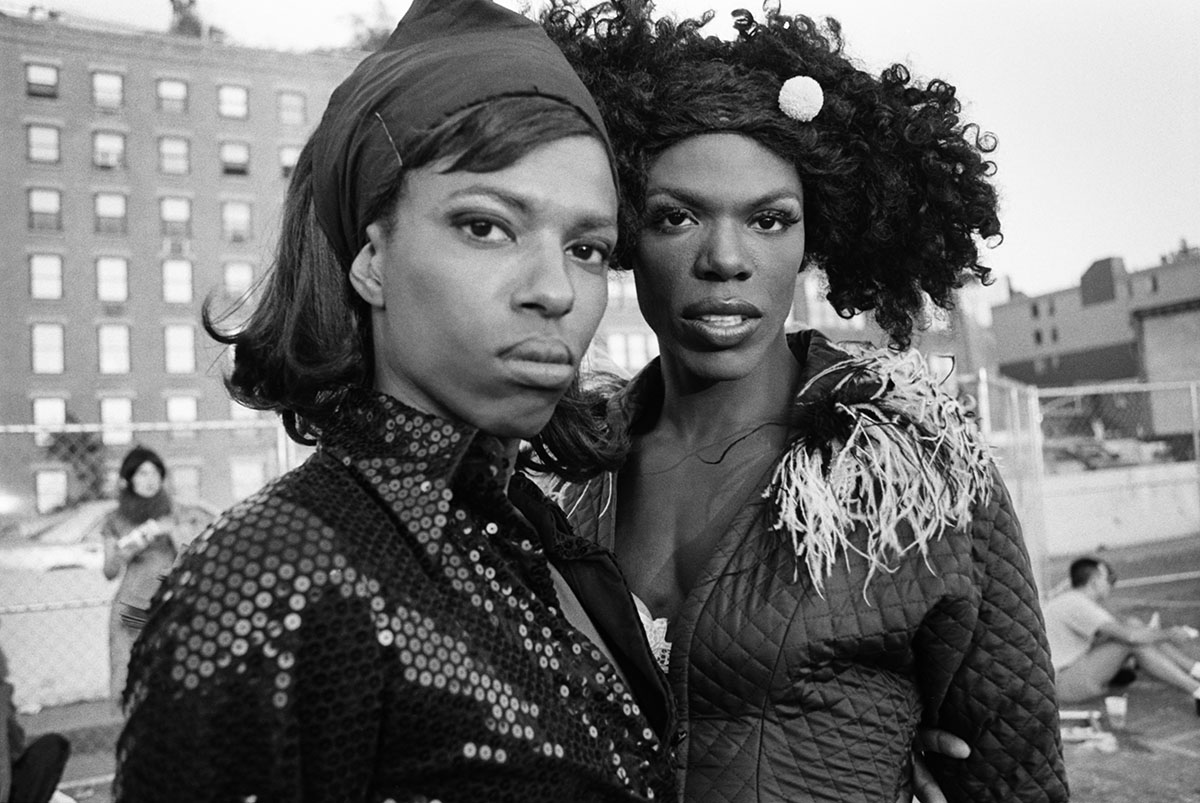

Look at the faces, the unlined and unburdened faces. Underneath the curls and hair spray, buried beneath makeup thick as a slice of bread, young fearless faces peek out. Faces young enough to forget, if only for an afternoon, the hatred, the fear and a generation’s worth of death, disease and terror.

Perhaps “forget” is not the right word. Let’s say “pretend.” Faces pretending, in the purest and simplest and most child-like way, which is very different from the bad habit of simply denying or avoiding reality; pretending, for an afternoon—a special, hot-as-hell summer afternoon—that freedom has no cost. Or, rather, that freedom costs as much as a cheap wig and cheaper makeup.

The 1990s were a break in the storm. Pierre Dalpé was there to capture the fun.

If the 1970s were a Golden Age for queer people, the 1980s were a time of horror, a Poison Age. By the time Wigstock surfaced and flourished, queers were sick of being sick, of being a beleaguered class, of the relentless hateful noise of the dominant voices. And damned well tired of the empty promise that if we behaved ourselves and assimilated, we’d be left alone.

No, we finally said. No.

No, and Watch Out, we’re coming through in ballgowns and busted heels. The tide had turned. We stopped asking for society’s help (help that would never come anyway), and instead started demanding space. And microphones. And a stage. Time for ourselves to be ourselves in all our messy, traumatized glamour. Every revolution starts on stage.

Within a decade, the young people in Pierre’s photographs saw many firsts. A burst of first “openly gay” politicians, celebrities, corporate titans, neighbours and friends lead the way, followed by the gradual but inevitable push for equal marriage, equal employment and equal life itself, an equal and safe life. Of course, the promise of true equality is always better than the daily reality, but a start’s a start.

And this is where the genius of Pierre’s photos is found. He captures that spark of optimism, the giddy and alarming moment when it is too late to turn back because you just don’t care anymore. Pierre went to Wigstock to have a good time. He came home with a coup in his camera.

In these cautious and fragile times, when an image can trigger an online civil war, a poem can lead to banishment and a tweet can get you fired, Pierre’s photos appear almost sneaky. They are not. These photos were taken long before we allowed ourselves to be turned into online commodities, before identity became something to trade and monetize, before everyone got so goddamned self-important.

Look at these beautiful outsiders, these utterly fearless people, arranging themselves for Pierre’s camera as they undoubtedly did hundreds of other cameras on those wondrous days; presenting themselves for public view without provisos, apologies or self-censorship. It’s easy to forget that before Selfies, before everybody had a camera and a “profile,” the construction of a self, an identity, true or better than true, took a lot of work. Work and guts. Again, look at these kids—they have more agency than a Hollywood cocktail party.

Pierre’s photographs are documents of a time and place, and, just as important, testaments to an ideal. The images speak to, and wholly embrace, a kind of plurality that few societies, and still fewer subcultures, achieve or even desire to achieve. The ideal depicted here is, of course, freedom. Freedom from stigma, from hate, from idiotically fixed and constricting conceptions of gender, from abuse, from being an object of speculation and derision.

At the same time—and here is the most delicious of ironies—every person in these photographs who was aware of Pierre’s camera made a spectacle of themselves in the best, truly giving way. That contradiction, that glaringly evident push-pull between not wanting to be treated like an attraction at a zoo and wanting, simultaneously, to be seen and seen clearly, creates a psychological tension in the photographs that is palpable and could never be rehearsed.

If you are queer, you know this tension well, because it plays out in your everyday life in hundreds of ways. You know you must be malleable, or not be at all.

The cagey glances and the abundant attitude turned toward Pierre’s lens are not new to you or me, because we know that queer lives are perpetually liminal—lives lived between power and powerlessness, acceptance and demonization. Queerness is instinctively performed, and can be as easily and suddenly erased. Queerness is fragile but ferocious.

In these photographs, a distant but not forgotten era awaits rediscovery: A moment when queerness let its hair down (or pinned it up, way up!) and the world became a little bigger.

Wigstock was an annual outdoor drag festival that took place every Labour Day weekend between 1984 and 2001—first in NYC’s Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, then later on the piers along the West Side Highway. The event morphed into various iterations; the latest, Wigstock 2.0, was in 2018 .

Photographer Pierre Dalpé documented the festival from 1992 to 1995. “The period I photographed coincides with the height of Wigstock’s popularity,” Dalpé says. “Wigstock included drag performances on stage, as well as musical acts, but the most exciting spectacle was the audience itself. Thousands of people converged upon the site in all manner of cross-dressing and gender-bending outfits, Halloween and carnivalesque costumes, as well as fetish wear.

“The years that I documented this event corresponded with a time when gender boundaries and trans politics were on the verge of a revolution; not just in the LGBTQ2 community, but in North American pop culture and beyond.”

Wigstock, Dalpé’s exhibition comprised of 24 photographs, was originally to show at Gaffa Gallery in Sydney, Australia as part of the Head On photo festival earlier this year. Though the festival took place after moving online, the gallery show was cancelled due to COVID-19 restrictions. R.M. Vaughan’s essay was originally commissioned for the gallery exhibition.

CORRECTION

Wigstock began in 1984. Incorrect information appeared in the original version of this story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra