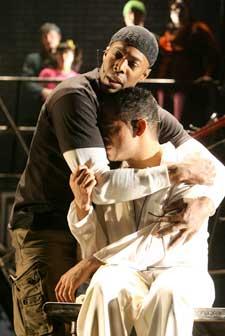

PANSEXUAL, PLAYFUL. Rent's libertine attitude is exemplified by the motor-mouthed, sex-loving, name-dropping, counter culture-praising La Vie Bohème. Credit: Joan Marcus

There’s no doubt that Rent shook the world of live theatre — and introduced a whole generation of young people to the musical genre with its debut in 1996.

Buzz grew steadily for the tantrumy, gender-bending, sometimes clumsy retelling of Puccini’s La Bohème. Rent picked up the Tony for best musical that year, aided by the Cinderella story and untimely death of its auteur, Jonathan Larson. Teens lined up for rush tickets to sit in the front rows. The franchise did a roaring trade in CDs, song sheets, T-shirts, posters and other memorabilia.

Gays swooned. We dug Rent’s swagger, its anti-corporate attitude, its sexual politics and its Tuesdays-with-Morrie message to carpe diem. Sure, it was schlocky and overlong. Sure, it cheated on the tragedy in the final act. But gosh darn it, wasn’t it fun to sing?

Now, as Rent returns to Toronto, one thing is abundantly clear: The more the world changes, the more Rent stays the same.

THAT’S SELLING OUT (BUT IT’S NICE TO DREAM)

Although it premiered in 1996, Rent has always been a historical drama — and not just because of its treatment of AIDS.

Its story arc covers the period from Christmas 1989 to Christmas 1990. Somewhere behind the curtain, floating in the zeitgeist, are the two political forces that had dominated the previous decade: Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. The dust had barely settled from the fall of the Berlin Wall. Here in Canada, Brian Mulroney’s brand of Bay Street capitalism was all the rage.

Money, in short, was king.

While not the main character, Tom Collins propels virtually every one of the show’s main themes. He’s a black, gay HIV-positive AIDS activist and a former squatter at the contested loft.

He’s an anarchist and an anti-institutional rebel. Indeed, whether being expelled from university or rewiring ATMs, Collins is nothing if not a shit disturber, poking corporate America in the eye.

With such a message, it’s strange, then, that Rent has become such big business — a 14-year, quarter of a billion dollar industry.

Michael McElroy, who has played Collins off and on since 1997, is well aware of the dichotomy.

“It’s two things that are in opposition: One of the main themes of the show is about being outside the mainstream, outside of what’s narrowly acceptable,” McElroy says. “And then you have this show that’s now a part of the world. It’s everywhere. Everyone knows it; everyone’s seen it, and it’s affected so many people.

“People said the same thing about the show Hair, because it was so antithetical at the time, and it’s become the voice of that generation. Rent does the same thing.”

And so we take their posturing with a grain of salt. Still, the protests of Maureen and Collins all these years later seem naïve. Many anti-corporate agitators have moved away from protesting McDonalds and Coca-Cola and toward forging alternatives: fair trade, organic and whole-food farming and the locavore movement.

Today, the cast’s rage, exemplified by their distaste for paying rent, feels dated, stale. Where, after all, are their strategies for resistance?

REASON SAYS, I SHOULD HAVE DIED

In a world of rapidly developing medical treatments for HIV and AIDS, Larson was wise to anchor the drama in the particulars of the time period. Circa 1990, AZT was the drug of choice for treating HIV; drug cocktail therapies were not yet widely available. And HAART therapy was still a twinkle in a researcher’s eye.

However, one thing that still rings true is the characters’ anxiety over HIV disclosure. What is managed off-handedly by Collins and Angel is a stumbling block for Roger and Mimi. Today, with gossip travelling faster than ever — and with the spectre of HIV criminalization haunting our personal lives — disclosure is still tough.

In the early days, HIV was almost synonymous with AIDS. Declines were often swift and steep. HIV was a far cry from the chronic, manageable condition that it is for many today.

Into this complex nest, the score drops two fuzzy odes to bravery and fear (Will I? and Life Support) and a pair of AIDS-related deaths.

Collins, of course, is the chief mourner, the backbone of pathos from which the audience’s sentiment hangs. McElroy is well aware of this.

“Immediately, when you start dealing with politics, people get their guards up and are ready to defend themselves. But by that point in the show, you’ve gotten to know the people,” says McElroy.

“By the time Angel is sick in act two, people have already fallen in love with him. They don’t remember even that he’s an HIV-positive drag queen from the East Village until act two when he’s in the hospital. They forget, because in the whole show, they’ve seen him in a Santa outfit.”

In poignant moments, Rent provides insight into those who had been given — as it was thought at the time — a death sentence. Mimi acts out while Roger sulks. Angel touches the lives of those around him while Collins becomes an activist. It sounds achingly familiar.

There is anger too, and it still feels relevant. The cast, pausing in the middle of Act One’s finale, shouts at the audience: “Actual reality! Act up! Fight AIDS!”

EVERY NIGHT, WHO’S IN YOUR BED?

Despite the sadness, Rent is essentially an uplifting affair — that’s why it still resonates. Among other things, a thread of hedonism runs through the text. Whether it’s Maureen’s bravado (Take Me or Leave Me) or Mimi’s party-girl antics (Out Tonight), a spirit of joyfulness surrounds the musical’s overt sexuality. Pleasure is good and worth looking for.

This may sound obvious, but you have to remember that many of the best iterations of gay life valorize suffering rather than pleasure. Think of Longtime Companion, The Boys in the Band and Philadelphia. For all the ridicule Rent generated (including a spoof in Team America), it’s nice to see a joyful attitude toward sex.

This attitude is exemplified by the motor-mouthed, sex-loving, name-dropping, counter culture-praising La Vie Bohème. In a series of toasts, the characters praise “faggots, lezzies, dykes, cross-dressers” and bisexuals, as well as leather, masochism, pain, dildos, masturbation, sodomy, shamelessness and Pee Wee Herman.

La Vie Bohème also toasts chosen family, celebrating “being an us for once, instead of a them.” There are other nods to the bonds of friendship and communal living in the way resources, whether money or booze, are shared.

“Take away the creativity, and you just have politics, in a way,” says McElroy. “With Rent, Jonathan [Larson] was talking about the time period, he was talking about the things he believed in. It was like, if I write this song, if I write this show, I can say these things through the voices of the characters, instead of hitting people over the head with it.”

The show’s reprise and finale are no mistake. It’s cliché, sure, but it encapsulates the joie de vivre missing from so many of Rent’s sombre relatives. That, if anything, is why Rent remains relevant.

No day but today, indeed.

Rent.

Jan 12-24.

The Canon Theatre.

244 Victoria St, Toronto.

$45-84.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra