“I know who you are, but you have to wear some lipstick, try a little harder.”

I sat in a chair in a brightly lit office in Los Angeles, opposite a beautiful woman — a talent agent. I understood the code, the words she didn’t say about my being a lesbian. I wore ripped, faded jeans and a leather jacket. I was, however, wearing makeup and wondered why she hadn’t noticed. Even this face-painting effort hadn’t won her over.

It was my Hollywood expedition, post–Emmy win for Outstanding Performer as Maggie in Maggie’s Secret. I was on the cover of Entertainment Weekly, and according to industry types, was on my way.

“Hang on,” she said as she lifted the receiver of the phone on her desk. “Hi, Marcia . . . I’ve got a new actress I want you to meet, a cross between Angelina Jolie and Jodie Foster. Tomorrow?” She smiled at me, nodding. “Perfect. Send the script over and I’ll give it to her before she leaves . . . Joanne Vannicola. Okay, talk later.” She hung up. “Okay, tomorrow you are going to 20th Century studios for an audition I lined up. Call me, and stay close to a phone so you can check in. And check your voice mail often.”

We walked out of her office and into a room where the script was being printed off for me, complete with binders and notes. This was not Toronto. But I was here to take the next step in my career.

“I’ll be calling you in a couple of hours after you settle. Where are you at again?”

“Oh . . . it’s near muscle beach, Santa Monica.”

“Be prepared to drive a lot.”

She ushered me through the reception area, where posters from her clients’ movies — Wesley Snipes and others — were hung, and out double doors the size of walls. I nervously said goodbye and made my way to the rental car, clutching my folder.

Driving out of the traffic of Hollywood to the ocean was a great way to escape. At night I would rent a bicycle to ride along the paths, wearing my helmet and long pants — the perfect Canadian, safety first — as I pedalled along the concrete pathways of the pier. I rode the Ferris wheel, trying to figure out why I wanted to be an actor, and wondered how I would fit my feminist lesbian identity into this mix.

Auditions piled up. Every day there were scene pages and scripts and calls from the agent. The other women in the waiting rooms were feminine, beautiful actors sizing me up. Everyone checked each other out, sideways looks and ears wide open trying to hear the others practising. Fierce competitors.

After three days I started having panic attacks. I tried to put on more makeup, bright red lipstick to go with my jeans and tees, but it didn’t make much of a difference. I still stood out, and not in the way that Hollywood embraced. I was auditioning for a movie being directed by Oliver Stone and couldn’t find myself in the characters I was asked to read for. Not that actors needed to find themselves, but I was so far from the characters in every way that I should have just auditioned for boy parts, might have had more luck. I cried my way to the car, didn’t know what to say to the agent in LA. I didn’t have the language for what I was experiencing — a reaction to homophobic undercurrents and extreme sexism, not just in the town, but also in the scripts. Everywhere.

“I was nervous. The giant billboards of Marilyn Monroe in the studios and old famous movie stars . . . it got to me,” I said to my agent on the phone, trying to give her a reason for choking at my last audition.

“That’s interesting,” she said.

What did that mean, interesting?

I hopped in my car on a Friday and didn’t call her. I bought a map and charted my route to San Francisco. I left, driving through Big Sur and Monterey, looking at sea lions and otters and touching the earth, seeing pelicans and gulls and a large pod of dolphins off a tourist boat meant for whale watching. Hundreds of dolphins chased the boat with such joy. For the first time in California, I had fun, away from women in heels and with implants and men with cameras and wandering eyeballs. The natural world could cure my panic, keeping me in the moment without thinking back into the past or too far ahead into the future. The natural world demanded I stay present so I wouldn’t miss one second as the dolphins jumped into the air and kept pace with the boat. I never felt a stronger love than when I was with animals or in nature.

I was running away from LA, and I found the nearest Goodwill, where I bought a pair of male slacks. I cut my hair and contemplated a tattoo, but didn’t know what to brand myself with. A dolphin? A turtle? A woman symbol? I finally decided against it.

The ride along the Pacific Coast Highway was good medicine. I was going to San Francisco, to Osentos, a women’s bathhouse where I’d sit in hot tubs with women like me. When I got there, I saw women with pixie cuts and eyeglasses, women with big breasts and little ones, with bellies that hung out over their pubic hair, women who seemed at home in their bodies. I sat in an outdoor sauna the size of a mini-trailer for two, with showers, under the stars and fenced in with vines and leaves. Women spoke to each other in loving ways and held hands or lay on the floor inside, meditating on mats and filling their lungs.

There were bars with poetry readings and gatherings of gay people openly displaying affection for each other on the sidewalks and in the markets of the Castro District and beyond. I ate and thought about more important things than self-obsession or judgment of bodies or the definition of feminine. There was art, politics, activism. This was the home of Harvey Milk, of my LGBTQ2 ancestors.

Standing outside a gallery a few blocks from my motel room, I saw eulogies in one-by-one-foot square patches for the AIDS quilt. I checked my messages and heard a frantic voice mail, so I called from the pay phone across the street from the gallery.

“Where are you? I’ve been looking for you. No one knew where you were,” the LA agent said to me.

“I’m sorry. Didn’t mean to disappear, just needed to get away,” I said, not knowing how to tell her how trivial and small it all seemed in comparison to the thousands of messages to the dead on the quilt.

“You can’t just take off to San Francisco when there are auditions happening. You didn’t even leave a phone number where you could be reached!”

That was on purpose.

“I know, sorry. I’ll call you when I’m back.” I hung up before she could carry on, gathered my backpack and notepad, and went to the nearest cafe. Before returning to my room, I stopped by the gallery again, and the AIDS quilt:

Sister X, died 1988.

James from Akron, died age 29.

Keith, he walked through our lives.

In memory of all the teens who died of AIDS.

There were patches with images of Betty Boop, Mickey Mouse, hand-drawn hands and rainbows; messages from lovers and friends and family — “You will live on in our hearts” and “Gone too young.”

Awakenings arrived at different times, and this was one of them. I knew I could not choose LA. There were no reflections of my people there. They may have wanted the Emmy Award–winning girl they saw in a show, but they didn’t want the young woman they saw before them. They didn’t want me. I was ahead of my time, culturally, and there was no space for queers.

No matter how hard it was to be a lesbian or a woman in the film business, it was not harder than the lives of children everywhere dying from war, famine, hunger, drought, or AIDS. But it was my life, and while the path would be difficult, I would have to find my way with determination, like many before me. No matter how hard the struggle for equity, I would take the harder route.

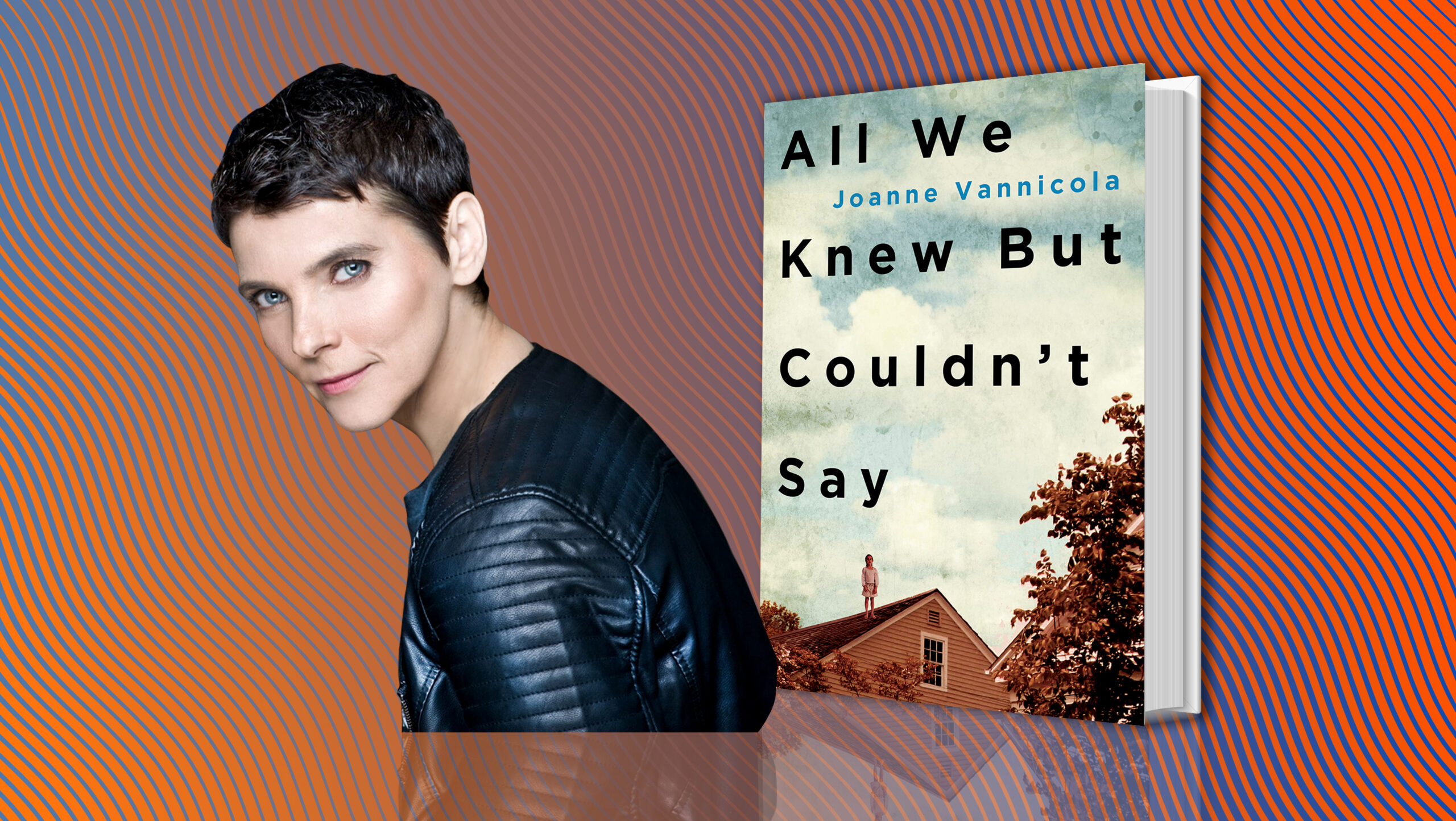

All We Knew But Couldn’t Say is available now.

Excerpted from All We Knew But Couldn’t Say by Joanne Vannicola © 2019, Joanne Vannicola. All rights reserved. Published by Dundurn Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra