When it was announced earlier this year that Dustin Lance Black would be writing a film about Civil Rights activist Bayard Rustin, I took a deep Black gay sigh. Yet another example of a Black queer story being told by an “ally.” Sure, Black gay playwright George C. Wolfe (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom) is set to direct, and Dustin Lance Black has the biopic credits. But penning a film about white gay men as a white gay man hits different than writing about a Black gay man when you’re not one. In a time where audiences are demanding authenticity at every stage of production, were all of the Black LGBTQ2S+ screenwriters too booked and busy?

Even if they were—they weren’t!—Black queer and trans folks are tired of non-Black (and sometimes non-LGBTQ2S+) folks controlling how our stories are told. And yes, I know that self-proclaimed allies can serve a purpose in and outside of the industry. But with a growing collective of Black queer and trans folks telling our communities’ stories, like Janet Mock, Justin Simien and Lena Waithe (and Cheryl Dunye and Patrik-Ian Polk before them), there’s little to no excuse for platforming an ally when capable members of the community exist.

This is not to say that white people and other supporters of Black LGBTQ2S+ folks absolutely cannot tell these stories or cannot tell them well. In fact, the receipts say otherwise. Paris Is Burning, the quintessential documentary on the lives of Black and brown LGBTQ2S+ people in New York City’s ballroom culture, was directed and produced by Jennie Livingston, a white queer woman. Bessie, the 2015 Emmy-winning made-for-TV biopic, was directed by Black lesbian filmmaker Dee Rees. She co-wrote it with white screenwriters Bettina Gilois and Christopher Cleveland. That same year, Tangerine, while led by Black trans actresses Mya Taylor and Kitana “Kiki” Rodriguez, was written and directed by two straight, cis white men, Sean Baker and Chris Bergoch. Then there’s 2016’s Oscar-winning Moonlight: The play it’s based on was written by Tarell Alvin McCraney, a Black gay man, but it was brought to the silver screen by Black straight director Barry Jenkins.

But it often seems like, in order for Black LGBTQ2S+ stories to be told, there must be white, straight and/or cis hands pulling some strings. Perhaps that’s just a byproduct of an industry still primarily led by and catering to whiteness. One day, I believe this won’t be the case, and Black queer and trans stories will be holistically developed by members of our communities every step of the way. But, like many hopes for changing media, we’re just not there yet. In consideration of this, I reached out to social justice organizers (from VOCAL-NY, Liberation House and the New York State Senate) whose work centres on building solidarity across identity markers to create a simple guide for non-Black and non-LGBTQ2S+ people wanting to uplift the stories of communities they don’t belong to. Through a people-centred approach, their suggestions for towing the fine line between advocating and promoting various narratives and simply taking up space came down to three principles: Conducting research, being introspective and playing the right role.

Conduct research

Research is as essential to film and television production as reading is fundamental to ballroom. Without researching the community whose story you’re telling, allyship goes awry. Like a social justice organizer, Hollywood creators must heavily consult with those within a community to actualize authentic storytelling.

“You have to canvas on the ground to understand the different perspectives [of a people],” said Paulette Soltani, VOCAL-NY’s political director. VOCAL-NY is a statewide grassroots organization that builds power among low-income, marginalized New Yorkers. “And while I can’t represent someone experiencing these injustices, I can say that 100 people are experiencing these injustices.”

“What the people want is a part of the research, too,” adds Tatiana Hill, a constituent advocate and organizer for New York State Senator Jabari Brisport.

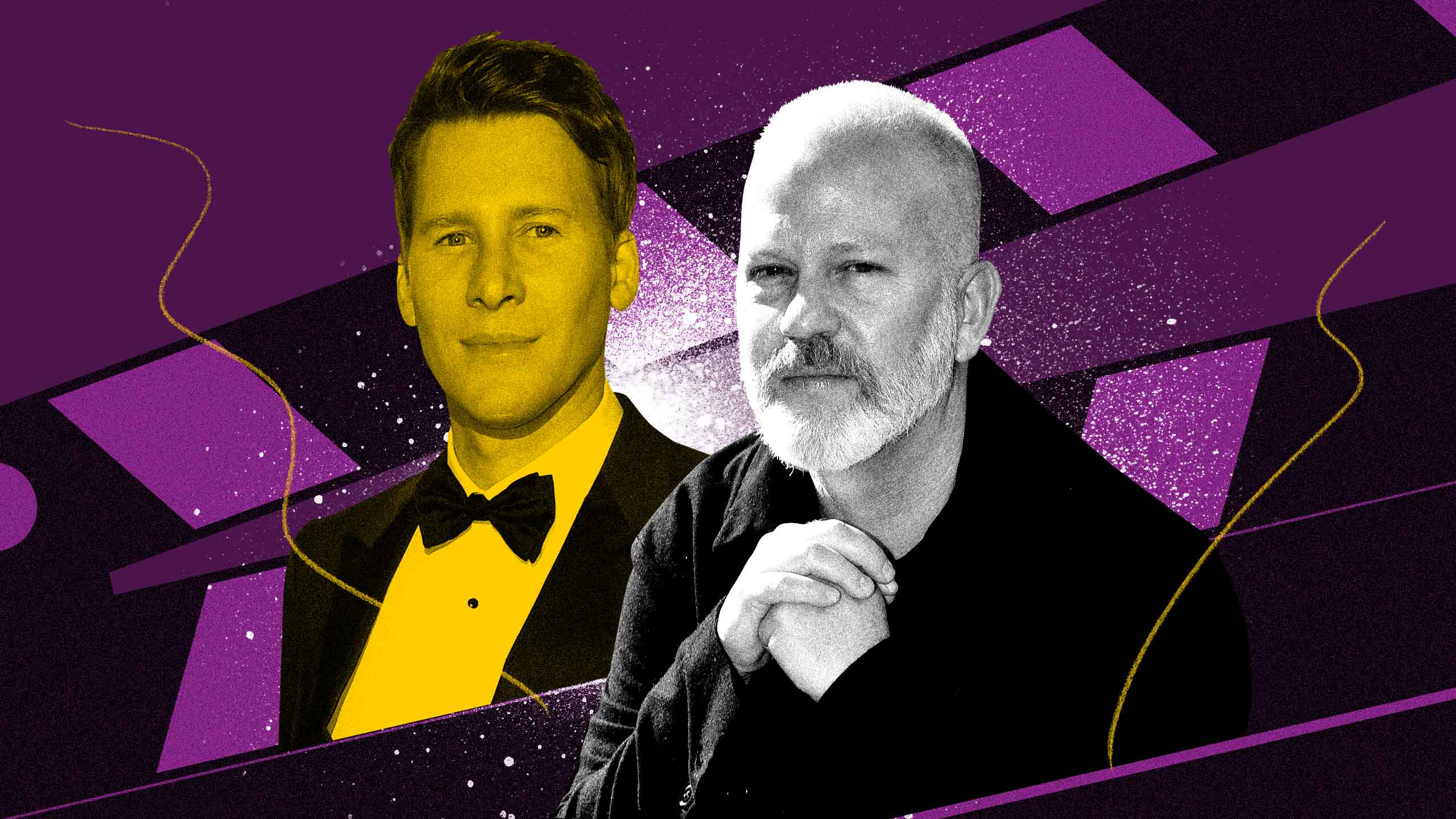

This is one of the reasons why folks love Pose, currently in its third and final season, so much. The Ryan Murphy-produced, Steven Canals-created series hired members of the ball community as consultants, choreographers, producers and cast—including Leiomy Maldonado, Twiggy Pucci Garçon, Dashaun Wesley and Jack Mizrahi Gucci, among others. They also brought in Janet Mock and Our Lady J as writer-producers to help craft the storylines of its trans leads. (That said, in light of Mock’s recent alleged statements about her pay, it’s also imperative to ensure the folks being brought on to help legitimize and authenticate a narrative are properly compensated.)

Be introspective

“You don’t know what you don’t know, and the things that you think you know, you need to question [if they] are canon or informed by assumptions,” says Clifton Garmon, VOCAL-NY’s chief of staff.

Creators must be aware of their own identities and the privileges that come with them. Lack of self-awareness often ensures that the voices one is supposed to uplift get silenced.

“Ask yourself: Why am I telling this story? If the response doesn’t have to do with the people that would benefit from your story, then perhaps you shouldn’t do it at all,” says Jawanza James Williams, director of organizing at VOCAL-NY. Telling a story that’s not to the benefit of the community most impacted by it, or without them in mind, dilutes it and potentially subjects the people in question to harm.

Take, for example, Academy Award-winning actress Halle Berry who, in 2020, expressed interest in playing a trans character. Needless to say, she had a “change of heart” upon proper introspection and honest conversations about the ramifications of cisgender actors playing trans characters.

Play the right role

If Viola Davis and Meryl Streep have anything in common, it’s that they know how to play their role—and allies in the industry should learn to do the same when it comes to telling stories outside of their community.

When you’re not the right person to tell a community’s story, you can utilize your platform and access to uplift and promote the story and its proper helmer instead. Take, for example,

Dee Rees’ 2011 feature Pariah, a semi-autobiographical account of her coming to terms with her sexuality as a teenager. An expansion of her graduate thesis, it became the award-winning canonical offering it is today thanks, in part, to her professor and mentor Spike Lee, who executive produced it.

Another great example is Starz’s P-Valley, the stripclub drama created by Katori Hall, a straight Black woman, that features the queer, non-binary Uncle Clifford (Nicco Annan). By having a co-executive producer in Patrik-Ian Polk, the prolific creator of Noah’s Arc and countless other Black queer narratives, Hall was able to ensure the character is well-rounded and more than just a stereotype.

Allies must keep in mind the systemic barriers that keep certain people out of decision-making roles and use their access to add seats to the table. “We are all telling these stories to spark some type of change,” says Jonathan Lykes, executive director of Liberation House, an organization that seeks to create sacred spaces for Black and Indigenous, queer and trans people. “But at the end of the day, we will all be better off when more people have access to make decisions.”

This story is published with support from the Ken Popert Media Fellowship program.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra