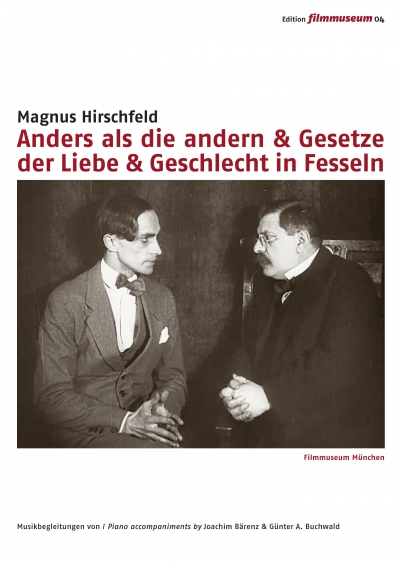

In the early days of cinema, a German sexologist made one of the world’s first pro-gay films. Lost to history after the Nazis rose to power, Gesetze der Liebe (Laws of Love) has been found, restored and released to the acclaim it deserves—nearly a century after it was made.

Gesetze der Liebe was released in 1927 by the renowned German scientist and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. Although the film was never shown in its entirety in Hirschfeld’s hometown of Berlin at the time of its initial release, the film received a belated premiere in the German capital this summer to an audience of about 50 people after the city permitted open-air cinemas. The film, painstakingly restored to Hirschfeld’s original vision by the Munich Film Museum, is scheduled for eventual release on DVD this year.

Hirschfeld was an important scientist and activist who was a pioneer in the field of sexual science. In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (SHC), which deployed scientific theories of human sexuality to advocate for the recognition of LGBTQ+ people, and campaigned against their legal persecution. By some definitions, the SHC was the world’s first LGBTQ+ rights organization.

A couple of decades later, in 1919, Hirschfeld created his Berlin-based Institute of Sexual Science (ISS), which soon became known around the world for its groundbreaking research on gender and sexuality; its medical team performed some of the world’s first gender-affirming surgeries. Hirschfeld’s influence came to an abrupt end as Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany. In 1933, students in support of the Nazis set fire to the institute as part of a “celebration” of Hitler’s hundredth day as chancellor—a rally that destroyed, among many other “un-German” books, the archives of thousands of case studies and photographs documenting LGBTQ+ lives. Hirschfeld, who was not only homosexual but Jewish, moved to France that year. He died of a heart attack two years later, in 1935, as Hitler’s Third Reich became increasingly authoritarian. Amidst all this, Gesetze der Liebe went missing.

Running 100 minutes, Gesetze der Liebe is structured as a series of lectures from Hirschfeld explaining sex and the reproductive system in the natural world. It’s considered to be an example of the “enlightenment film” (Aufklärungsfilm) trend that was popular throughout Weimar-era Germany. These enlightenment films aimed to educate audiences about topics such as drug and alcohol use, sex work, abortion, sexually transmitted infections and, in the case of Gesetze der Liebe, sexuality.

For Hirschfeld, the film was also an opportunity to draw attention to anti-gay laws in Germany at the time. In particular, he targeted Paragraph 175, a statute prohibiting sex between men (women were not mentioned) that was introduced in 1871 and was used to convict around 140,000 men until it was repealed in 1994. In its long history, the statute was at times poorly enforced and at times strictly enforced. The Nazis took a particular interest in it when they came to power in 1933. In 1935, after the institute had been destroyed and Hirschfeld had left the country, the Ministry of Justice amended the statute to make it even more strict, so that even words and gestures between men that could be construed as sexual were against the law; the Nazis also increased penalties for violating Paragraph 175.

In his day, Hirschfeld was “very aware” of the way film could be used to inform audiences and influence public opinion from the start of the medium’s popularization in the early 20th century, says historian Rainer Herrn of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society.

“The third chapter tells viewers about the maternal instinct of different species, such as birds tending to their nests and the watchful eye of a kangaroo looking after her joey.”

“One argument for stopping [the reform of sex laws] was that the public was not ready to accept the abolition of Paragraph 175,” Herrn says. “Hirschfeld says, ‘Then I have to enlighten the public.’ And he believed film would be the best way.”

Gesetze der Liebe is divided into five chapters, of which the first three appear to be fairly innocuous explanations of mating behaviours in different plant, insect and animal species—explanations that might not look out of place in a school biology lecture. In the first chapter, “Searching for and Finding the Sexes,” viewers witness the courtship patterns of various frogs, crickets, birds, fish and snakes, including the day-long copulations of European adders. The second chapter, “To the Light of the World,” follows the creation of life from fertilization to birth, demonstrating the diverse ways reproduction takes place, from bees and other insects fertilizing flowers to eggs laid underwater by fish and amphibians to the more familiar mammalian reproduction in animals such as the common house cat. The third chapter, “Mother’s Love,” tells viewers about the maternal instinct of different species, such as birds tending to their nests and the watchful eye of a kangaroo looking after her joey, before arriving at the role of a mother’s love in humans.

According to Herrn, many of the scenes in these chapters were captured by Hirschfeld and his colleagues at the ISS. This footage provides viewers with an extremely intimate and scientific view into these diverse expressions of sexuality in nature. The chapters are interspersed with scenes of Hirschfeld himself as he lectures about the content of the film, frequently drawing attention to the fact that non-heteronormative behaviour is common throughout the natural world.

The final two sections discuss Hirschfeld’s more controversial theories of sexuality. In the penultimate section, he details his theory of “intermediate sexes,” meaning that not only are there men and women, but also men who have “female traits” and women who have “male traits.” One example he employs from the “animal world” is the hermaphroditic slug, which has both male and female reproductive organs.

“Although the film can be considered a good example of using media to agitate for the reform of anti-gay laws, Herrn has problems with the way the film frames sexual identity.”

This view is not quite the spectrum of sexuality we think of today, but rather was looking at what the body, rather than a person’s identity, suggests about gender identity and sexual orientation. “He argued in a very biological sense,” says Herrn. Although the film can be considered a good example of using media to agitate for the reform of anti-gay laws, Herrn has problems with the way the film frames sexual identity.

“It is arguing, in an essentialist way, that homosexuality is an inborn trait caused by hormone imbalances, and that is very problematic,” he says. “Then you could provide the tools to extinguish homosexuality because you propose [that it was a disorder], it could be treated.” (Hirschfeld’s view, though out of date now, was advanced for the time. This is a similar line of thinking that, for example, led the American Psychiatric Association to list homosexuality as a disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), leading to harmful attempts to “cure” homosexuality; the definition was removed from the DSM in 1973.)

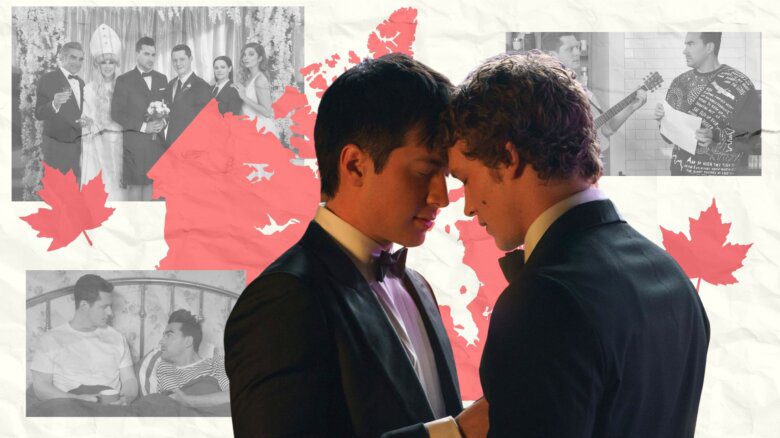

The fifth and final section of Gesetze der Liebe is dedicated to homosexuality, and is actually an abridged and restructured version of a feature-length film Hirschfeld had co-written with Richard Oswald (who was also its director and producer) about eight years earlier. Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others), released in 1919, is considered to be the first pro-gay film in the world.

“Soon, their budding romance is disrupted by the prejudices of family members and a male sex worker who blackmails the musician.”

Likely running between 60 and 80 minutes when it was originally released, Anders als die Andern is a drama about a concert violinist who falls in love with his male student. Soon, their budding romance is disrupted by the prejudices of family members and a male sex worker who blackmails the musician. The central message of the film is the ways that Paragraph 175—and the stigma and prejudice it bred about homosexuality—destroyed the lives of gay and bisexual men in Germany at the time.

The original version of Anders als die Andern was released in 1919 to great success in Berlin, where it was shown in theatres for several weeks. However, it also generated great controversy, and became one of the first films to be subjected to Germany’s new censorship laws the following year on the grounds that the drama constituted “homosexual propaganda.”

Nearly a decade later, Hirschfeld released a shorter version of Anders als die Andern as the fifth part Gesetze der Liebe. Herrn speculates that this was an attempt by the sexologist to sneak the censored film past authorities. By hiding his more controversial theories and the story of a victim of Paragraph 175 in an “enlightenment film” with lectures about sexuality in the animal kingdom, Herrn says it’s possible Hirschfeld thought it might make it past the censors, be viewed by mass audiences and influence public opinion.

This plan was a failure, as authorities immediately censored the parts of Gesetze der Liebe on “sexual intermediacy” and homosexuality. However, Hirschfeld continued to try to get around the laws. The prohibition against “homosexual propaganda” only applied to moving images, so Hirschfeld hosted viewings of the first three uncensored chapters of the film, followed by a lecture with slides of stills from the more controversial final two chapters, says Stefan Drößler, director of the Munich Film Museum.

“After Nazi supporters committed arson against Hirschfeld’s institute in 1933, it was believed that both the the entirety of ‘Gesetze der Liebe’ had been lost forever.”

As with Anders als die Andern, Hirschfeld’s new part film/part lecture presentation was a huge success. The sexologist repeated these presentations weekly in a major Berlin cinema that seated a couple of thousand people, and even travelled beyond the capital to present the film in Hamburg.

After Nazi supporters committed arson against Hirschfeld’s institute in 1933, it was believed that both the feature-length version of Anders als die Andern and the entirety of Gesetze der Liebe had been lost forever. However, the abridged and restructured version of Hirschfeld and Oswald’s 1919 drama was preserved in a Russian archive with Ukrainian intertitles, and resurfaced decades after the war. It’s likely that this version of Anders als die Andern was the one that Hirschfeld had initially tried to sneak into Gesetze der Liebe before it was censored.

The Ukrainian version of Anders als die Andern enjoyed a brief revival in the 1970s, when the East German Film Archive received the film from the Soviet Union. “They showed it in [East] Berlin in a little cinema for archival treasures,” Drößler says, adding that people from the gay scene in West Berlin crossed the border for viewings.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that there was interest in translating Anders als die Andern back to German and restoring it to its original format. When Drößler first started working on restoring the film in the early 2000s, he realized that not only was the only surviving version of Anders als die Andern shorter than the original, it was also out of order. Meanwhile, the rest of Gesetze der Liebe was considered to have been lost.

“It’s spooky…. It’s a repetition of the past.”

Drößler began the painstaking process of piecing together the feature-length film using the surviving pieces of footage and booklets that Hirschfeld sold during screenings, in which he described in detail the contents of the film.

“For Hirschfeld, it was always clear that his films could be censored,” says Drößler. “That is the reason why he produced these books.”

Although the Munich Film Museum’s restoration is impressive, Drößler admits about a third to half of the original version of Anders als die Andern remains missing. Based on Hirschfeld’s pamphlets, he knows there were flashbacks and scenes with the protagonist’s sister and parents, including a moving scene at the end of the film where his family comes together after the protagonist dies by suicide.

In the reconstructed version of Anders als die Andern, Drößler has inserted some still images and new intertitles based on photos and text in Hirschfeld’s pamphlets in an attempt to make up for the missing materials.

It was while working on this restoration project that Drößler discovered the first four reels of Gesetze der Liebe in the German Federal Archive. These reels, which were previously assumed to have been destroyed or lost, were edited back together, again using Hirschfeld’s pamphlets to reconstruct the version of Gesetze der Liebe that, at long last, premiered in Berlin this summer.

Now, about a century after this saga began, both films will finally be released for a general audience. The Munich Film Museum will release both Gesetze der Liebe and Anders als die Andern, along with Geschlecht in Fesseln (Sex in Chains), a film from 1928 that also addresses themes of homosexuality, on DVD by the end of the summer. The museum is in talks with U.S. film distributor Flicker Alley about releasing the films for a North American audience with English subtitles.

Drößler says it’s vital for people to view these historic films today. “I think it is important to understand how things were suppressed in the past, but also to see what was possible for these pioneers like Hirschfeld to do,” he says.

About a century after the release of these films, similar arguments about “homosexual propaganda” are being used to suppress the expression and organizing of LGBTQ+ people in several European countries. In the past few years, dozens of towns in Poland have declared themselves “LGBT-free zones” with support of the federal government, and this summer, Hungary’s parliament passed a law banning LGBTQ+ content in schools.

“It’s spooky,” Herrn says. “Approximately 100 years later, the same argumentation is now guiding the Hungarian parliament, like in Germany in 1921. It’s a repetition of the past.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra