Heather María Ács tells people how to have sex on camera for a living. Or rather, she tells them how to pretend to have sex—safely, consensually and in ways that can arouse viewers, sure, but also in ways that can challenge, reflect, move and amuse an audience. “I personally love some levity in a sex scene,” she says.

Ács is an intimacy coordinator, part of a field that has its origins in the theatrical practice of intimacy direction originally conceptualized by Tonia Sina in 2006. Intimacy coordination rose to prominence during the #MeToo movement, as the reckoning with the sexual misconduct perpetrated by powerful men in film and television cast light on the industry’s wider climate of exploitation. Ács works with actors and filmmakers to make sure everyone who is part of scenes involving sexuality, nudity and intimacy understands and consents to everything that happens.

Both the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television, and Radio Artists (ACTRA) and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) strongly recommend that anyone making a film including scenes that involve nudity or simulated sex use an intimacy coordinator. There’s no formal stipulation that productions use an intimacy coordinator, although many in the field believe there should be, and some production companies, including HBO, now require them for all intimate scenes.

Ács says intimacy coordination is a natural extension of her queer Anglo/Chicanx identity, and of her work as an artist, writer, director, performer and educator in both academic and BDSM and kink spaces. The field of intimacy coordination is young, but Ács can already see the ways in which it can grow to serve more people, better. She still finds herself pushing back against heteronormative assumptions on set, asking as a heterosexual sex scene is choreographed, “and will the woman orgasm also?”

Ács works with an organization called Reps On Set, a queer, BIPOC-led group of intimacy coordinators and mental health professionals working to advocate for under-represented people in media. “Ideally, I’m telling stories that push against the patriarchy,” she says. Xtra spoke with Ács about how she came to intimacy coordination, how her queerness informs her work and her hopes for the future of film.

I didn’t realize until speaking with you how new intimacy coordination is as a profession.

I know! What the hell was going on before intimacy coordination? Literal sexual assault was happening onscreen in films that are upheld as the greatest films of all time. Something that blows my mind and makes me excited is that for some young actors, their first intimate scene ever will be with an intimacy coordinator. That will be their experience throughout their whole careers.

What else about intimacy coordination might people not realize?

I often see scripts that just say, “They have sex.” It’s my job to say, “Okay, great! Lots to work with!” We take into account not only the story, but also the technical set-up: how long is the shot, where is the camera, what are we allowed to show? Another less glamorous part of the job is working with the legal department on simulated sex and nudity riders in performers’ contracts. And we might also help with choreography, and share expertise on things like BDSM and kink.

We also facilitate communication between the director, production and the actors, because there’s a power dynamic there. It’s not just about safety, it’s about professionalism: this is what it is to be professional now. People often say “an intimacy coordinator is like a stunt coordinator, but for intimate scenes.” And for stunts, you would never ask, “Should we be safe and hire a stunt coordinator?” It’s about respect and professionalism.

Ultimately, an intimacy coordinator is there to support the vision of the artists involved, and help them tell the story they want to tell with safety and consent. I create a safe and comfortable space to talk about intimacy and sexuality, which often means I’m helping to create the professional context that says, “It’s normal to laugh, it’s normal to get shy,” but also sets boundaries.

How do you feel like your identity and experiences inform your intimacy coordinating?

All intimacy coordinators are expected to be knowledgeable about and respectful of people’s genders and sexualities, and pay attention to which modesty wear [garments actors wear during intimate scenes that allow them to appear nude, without actually being nude]—which is such a funny term, not the most sex-positive—will be comfortable for people of all different genders. That said, I think my queerness, my involvement in BDSM and kink and the intersection of my background as an educator in general and a sex educator absolutely inform my practice. I have that knowledge, because I’ve lived it. Identity informs all our work, but with intimacy coordinating it feels more direct.

I’ve worked with directors who wanted a queer intimacy coordinator specifically because they weren’t queer and they were committed to authenticity, and I’ve worked with queer directors who wanted to work with someone they could relate to and trust. As a queer person who sees and is intrigued by the expansiveness of human sexuality, and as someone with a commitment to being good at my job, I am always questioning power dynamics, and asking questions that expand the rote heteronormative physical actions we often see. If I’m given a heteronormative scene with two cisgender actors who are male and female, I look for ways to play with power dynamics that are still authentic to those characters and the storytelling in the script. And most of the actors I work with, especially the female actors, are looking for that also.

That perspective sounds very related to your work with Reps On Set.

Absolutely. We try to offer people someone to work with who represents who they are as much as possible, which is a direct reflection of coming from a radical, queer, social justice-focused background. If a job came through that was Latinx-focused, a production might ask for me specifically, and I would be very excited. I want to see all bodies represented. I want to see fat bodies, curvy bodies, brown bodies, Black bodies, being represented in the most beautiful, gorgeous, sexy way.

I can imagine how vulnerable this must be for the performers, for the filmmakers and for you too. Can you share a time when you felt like the importance of what you brought to set was especially clear?

A time that comes to mind is from a scene I was working on that involved a non-binary actor, and the character they were playing used pronouns different from their own. I asked if I could advocate for them to make sure the cast, crew and even legal team were addressing them correctly, and they said yes, they would really appreciate that advocacy. Everyone was happy to have guidance making sure this actor felt comfortable, and that made it a great experience.

The actor shouldn’t have to worry about all of this. They should be focused on their character and their job, which is acting. I feel that often queer people in any field have advocacy attached to their role as a part of being who they are, which isn’t fair. If people are comfortable in that role, great, but not everyone is.

We’re living through a time of intense cultural and legislative attacks on queer and trans people. How do you see your work in media in that context?

Media is beyond powerful. If media weren’t powerful, and if queer people weren’t powerful, then they wouldn’t be trying to control us. I grew up in the [U.S.] South, in a smaller place. We can talk politics all we want, but what do young people have access to? Media.

There are so many ill-informed, ill-intended, just plain bonkers portrayals of queer sex and sexuality out there. Do you feel like your work gives you an opportunity to affect the accuracy and care around those portrayals?

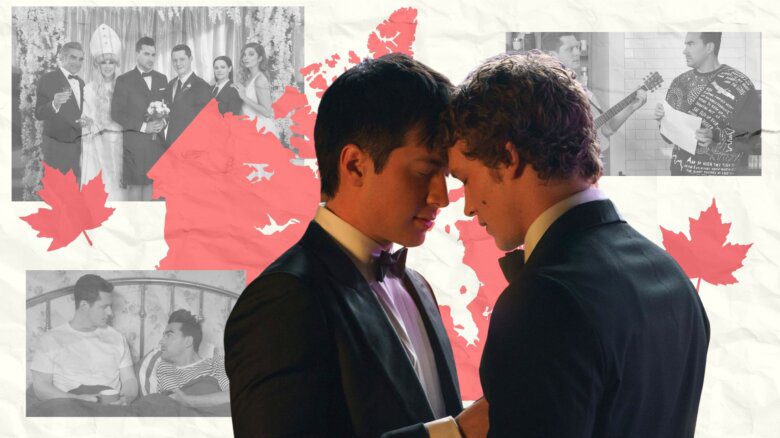

It’s so beautiful when my job gives me the opportunity to show up for my community. I have a commitment to supporting the portrayal of authentic queer sex and sexuality, and there’s no one way to have queer sex. When I’m the creator, sex feels authentic to me when it’s heightened. The sex I have is not like doing the dishes, it’s like going to another dimension. But I’ve also worked with queer filmmakers who had different experiences of sex and sexuality than I do, and that’s also so fun. When something is truly queer, it’s never monolithic.

There can also be great conversations with filmmakers who don’t identify as queer about how to make a queer sex scene awesome. But if you’re waiting for mainstream media to offer you the imagery you desire in terms of representation, you’re gonna be waiting for a while. As queer people, we need to be making our own stuff in every medium. I’m committed to queer people getting the things they want and need, and that includes support around intimate scenes. That includes queer filmmakers, especially queer indie filmmakers, and anyone who hasn’t worked with an intimacy coordinator before and would like to.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra