It’s 1991 and I’m sitting in a dark theatre on a December night when I feel a stirring.

As the junior film critic for Toronto alt weekly NOW, I was sent to review Fried Green Tomatoes, a holiday release from first-time director Jon Avnet that wasn’t garnering much buzz compared to the season’s bigger films, including JFK and The Prince of Tides.

I had never heard of the book on which the film was based, Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, and the cast, a quartet of stars featuring young actors Mary Stuart Masterson and Mary-Louise Parker working alongside Oscar winners Kathy Bates and Jessica Tandy, was unconventional.

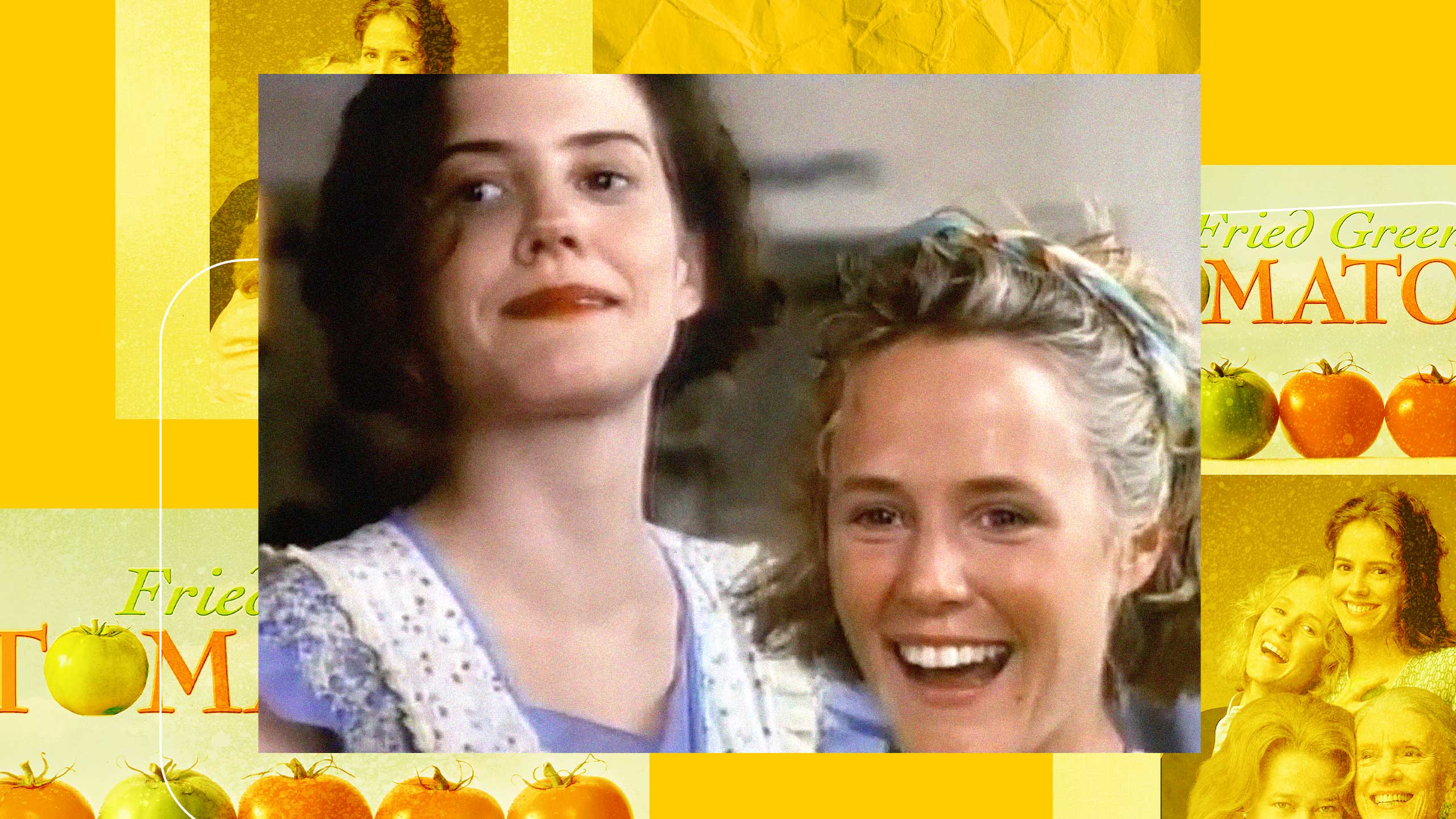

The lights go down and before long I’m transported back to 1920s Alabama and mesmerized by a blonde tomboy named Idgie (Masterson) and her endearingly slow-talking companion Ruth (Parker). While it is never explicitly shown, it is obvious Idgie and Ruth are in love with one another, and that gives me all sorts of feels.

I am 28 years old and not yet out—not even to myself; I’ve been pushing my feelings of attraction to women down, afraid they will bubble to the surface. But I am on the precipice, and within the next year I will wake up one morning and say to myself, “I’m gay and that’s okay.” I’ll come out to myself and my loved ones, and I will begin dating women. But in that theatre, on that night, all I know is that I adore Idgie and Ruth and my heart melts whenever they look at each other.

If you were a lesbian in 1991 you know what I’m talking about. Fried Green Tomatoes was the gift we didn’t expect. And while it comes up short in terms of being an open and frank film about female love, it felt good enough for a time when mainstream Hollywood was deathly afraid to show lesbians onscreen. Earlier that same year, history was made with TV’s first lesbian kiss on L.A. Law, which turned out to be nothing more than a hollow ratings grab. We’d have to wait another six years for Ellen Degeneres to come out on Ellen; while we stood up and cheered, it cost Ellen dearly, derailing her career for years.

Fried Green Tomatoes kicks off in the present day with the meek Evelyn Couch (Bates) visiting a nursing home where she meets the feisty Ninny Threadgoode (Tandy). Ninny begins to recount the story of Idgie Threadgoode, and through flashbacks we meet the rambunctious young woman who lives in the woods and cavorts with folks from the wrong side of the tracks.

Enter Ruth Jamison, a gentle and proper young woman who is asked to try and tame Idgie. That she does, and we see them bond in a glorious picnic scene in which Idgie puts her hand inside a beehive to retrieve a honeycomb, dripping with nectar, to give to Ruth. The camera lingers on Ruth as she looks on in amazement and adoration at Idgie, saying, “You’re just a bee charmer Idgie Threadgoode, that’s what you are, a bee charmer.”

Their butch/femme dynamic fuels the film: Idgie saves Ruth and her baby from her abusive husband Frank, they open a cafe together, live under the same roof and when the villainous Frank returns to steal the baby, he is murdered. (Although we don’t see who killed him, we assume Idgie took care of that for Ruth as well.)

The story of Idgie and Ruth’s unconventional life together inspires Evelyn to take charge of her own life, and we watch as she transforms from a depressed homemaker catering to her husband to an independent-minded woman.

I remember leaving the theatre enthralled, and while I felt that the attraction between Idgie and Ruth was powerful, stretching beyond platonic, I wasn’t ready to name it. In my review of the film, I described it as a “moving homage to female companionship.” I see those words now and I cringe. They may be partly true, but they read like code, hiding the full truth—just like I was hiding from myself.

This year marks the film’s 30th anniversary, and I felt the need to revisit the movie. I’ve seen it many times, but not in the last 20 years.

I sat down with my partner and settled in. But I was quickly taken aback; I had forgotten how deeply problematic it is, beginning with its treatment of its Black characters, who are one-dimensional and subservient. Idgie and Ruth are depicted as white saviours and without prejudice (despite remaining good friends with a known Klansman).

I realize the film I love could not be made today. It’s a relic of its time, the brainchild of Flagg (who also co-authored the screenplay), a Southern writer with a deep knowledge of her region’s history but also a writer tainted by that same past.

Flagg started her career as an actor, had small roles in films (Five Easy Pieces) and on TV, and is probably best known for her appearances on the 1970s game show Match Game. By the late 70s she turned her focus to writing, and met fellow lesbian writer Rita Mae Brown (Rubyfruit Jungle). They lived together for a period of time, although as Brown recounts in her memoir, Flagg didn’t want the pair to be seen together in public. She remains one of our reluctant lesbian authors: out, but not so out.

I do give Flagg credit for creating Idgie Threadgoode, an iconic butch character, even though in the film she’s dressed in the Hollywood version of butch: clean, crisp men’s shirt and overalls with one shoulder buckle undone, looking like she stepped out of a 1980s Ralph Lauren ad. Her look was meant to keep Idgie on the straight side of gay. A New York Times reporter visited the film set during shooting and asked Masterson if the film stays true to the book, which makes it clear that Idgie and Ruth are romantically involved.

“It’s definitely an implication as far as I’m concerned,” said Masterston. “But I think probably what Jon [Avnet] feels is that it’s not the point of the movie.”

You can’t blame the 25-year-old Masterson for toeing the line. At the time, admitting to playing a lesbian would have been career suicide, and her career was just taking off with her stellar turns as a teen mom in Immediate Family (1989) and as a tomboy drummer in Some Kind of Wonderful (1987).

In Fried Green Tomatoes she plays Idgie as awkward and self-conscious, delivering her lines while glimpsing at the camera as if she’d rather be somewhere else. Her awkwardness, however, is outdone by Parker, who plays Ruth as a watchful woman keeping an eye on Idgie, her dialogue drawn out in a strange, shy, alluring way.

It seems right that two unconventional performers should play two unconventional characters, and I’ve always held a soft spot for the pair of them, watching the ups and down of their careers.

Masterson kept busy in the 1990s, starring in Benny & Joon opposite Johnny Depp and in the all-female western Bad Girls, but big-screen stardom eluded her, and she’s spent the last few years appearing on TV and stage. She finally did play an out lesbian, starring as the wife of Indira Varma’s prison warden character on the short-lived TV show For Life.

Parker’s star shone brighter: she’s a bonafide Broadway star, winning two Tony Awards for her turns in Proof and The Sound Inside, and is most famous for portraying pot-selling mom Nancy Botwin for eight seasons on the Showtime hit Weeds.

For all its faults, Fried Green Tomatoes gave queer viewers a tantalizing taste of lesbian love and kicked off the golden decade of lesbian cinema—one that dripped with such juicy fare as Go Fish, The Watermelon Woman, All Over Me, Bound, The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love, Fire, Aimée & Jaguar, But I’m a Cheerleader and High Art.

So I will always be grateful for that December night 30 years ago when I first met Idgie and Ruth. When I think of them now, I imagine them on a country road, waving me forward, telling me to follow them—and I do.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra