Early in Bruce LaBruce’s Saint-Narcisse—the director’s first narrative feature in two years, opening in select theatres in the next week—Dominic (Félix-Antoine Duval) comes home to find his grandmother falling asleep while watching a religious television program. As the on-air preacher testifies to the way Jesus freed him from the burden of sin, Dominic turns it off and warns her that shows like that will give her nightmares. Ever the provocateur, LaBruce uses his new film to dissect the nightmares of a patriarchal religion before showing his own way of getting out from under the burden of sin.

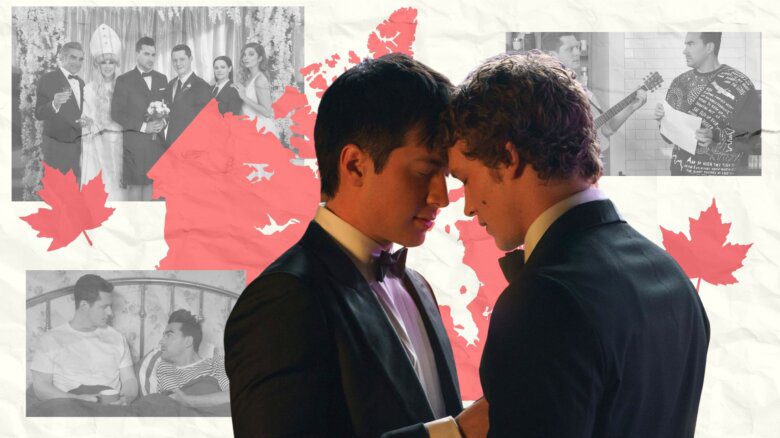

That sounds awfully coherent for a film from Canadian cinema’s leading queer outlaw. Though Saint-Narcisse is one of his most polished and focused films, made with his largest budget to date—and with a focus on family that almost seems out of character for LaBruce—it still reflects the sensibility of the man who created the groundbreaking No Skin Off My Ass (1991), the fantasia on the skin trade Hustler White (1996) and the queer/punk revolutionary satire, The Raspberry Reich (2004). The opening shot of Saint-Narcisse is a closeup of Duval’s jean-clad pelvis, a reminder that the film maintains LaBruce’s queer/punk aesthetic. The plot is couched in the conventional materials of melodrama (strange coincidences, family secrets, guilt and jealousy) while also featuring bursts of its director’s off-beat humour.

The opening sequence warns us that we can never be sure what we’re looking at. The camera moves up from Duval’s pelvis to show him staring straight into the lens. It’s unsettling. Is he looking at us? LaBruce then cuts to clothes tumbling in a laundromat’s dryer, the real object of his gaze. That’s interrupted as Dominic drifts off to sleep and dreams in flashes of a hooded male, his face obscured. As Dominic folds his laundry, a young woman starts flirting with him, turned on when he explains that he’s doing the wash for his invalid grandmother. The two begin to make love, unaware of the crowd gathering outside the laundromat’s front window to watch a scene straight out of soft-core straight porn. Duval notices the crowd, spies the hooded figure from his dream among them and wakes up at the point of orgasm. In just a few minutes, LaBruce has conditioned us not to trust anything we see, while also having his way with the politics of contemporary courtship and gender roles.

That imagined encounter is the only sexual connection Dominic can handle, at least at the film’s start. His true object of desire is himself. The film is set in 1972, and Dominic has acquired one of the newest technological developments of that era: a Polaroid SX-70 camera, which he uses to take pictures of himself that he gazes at while masturbating. That’s both a sardonic commentary on contemporary society—in which social media has provided a form of instant narcissism as people post pictures of possessions, the food they’re eating and themselves—and a comment on outdated theories of homosexuality that view it as a form of self-love. As it will turn out, however, Dominic’s seeming narcissism is actually a yearning to fill an emptiness within himself, to identify a lack he’s been instinctively aware of since childhood.

When Dominic’s grandmother dies, he discovers among her belongings letters from Beatrice (Tania Kontoyanni), the mother he had been told had died while giving birth to him. He traces her to Saint-Narcisse, a small town in Quebec, where, in a group of passing monks, he spots a familiar face—his own. After meeting his mother, he learns that when she was pregnant, she had an affair with another woman. Her husband found out and, when her labour ended, told her she had given birth to a single stillborn child. As Dominic discovers, she had actually delivered twin boys, and the other, Daniel (also played by Duval), was sent to a Catholic orphanage. It’s a convoluted backstory that gets even more twisted as we learn that Daniel is involved in an abusive relationship with the monastery’s head, Father Andrew (Andreas Apergis), who believes Daniel to be the reincarnation of St. Sebastian.

With its use of doubling and twisted family secrets, the film has echoes of Hitchcock, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Robert Altman—particularly the Images (1972) and the Three Women (1977)—and such classic Hollywood soap operas as Peyton Place (1957) and the films of Douglas Sirk. The film also takes a great deal of inspiration from Paul Almond’s metaphysical trilogy (1968’s Isabelle, 1970’s The Act of the Heart and 1972’s Journey). From all three, LaBruce draws on the fascination with previously taboo subject matter, particularly the incest in Isabelle and ecclesiastical sex in The Act of the Heart. There’s even a nod to Brian De Palma’s Sisters (1972), with LaBruce naming his lead characters after Dominique and Danielle (Margot Kidder), the conjoined twins in De Palma’s film. LaBruce reflects all this in the film’s historical setting and visual style. Working with Quebecois cinematographer Michel La Veaux, who started his career in the 1970s, he mirrors ’70s cinematography, using lenses and lighting kits from the period.

With twins separated at birth as a key plot point, it’s not surprising that LaBruce uses other mirrors throughout the film. Beatrice is living with a younger love, Irene (Alexandra Petrachuk), a relationship that is paralleled by the strange mentor-protégé relationship between Father Andrew and Daniel.

LaBruce takes an even deeper dive into melodrama when Irene finds herself attracted to Dominic, possibly seeing him as a long-lost brother. Although derided as pseudo-science, the idea of “genetic sexual attraction”—used to describe sexual feelings between family members who don’t meet until adulthood—is something that turns up in soap operas. In Saint-Narcisse, it sets up a mother-son-foster daughter romantic triangle that’s visually reflected in an emotionally stunning scene in which Beatrice spies on Irene spying on Dominic as he masturbates while looking at pictures of himself.

Nor is it any surprise that, when Dominic finally meets Daniel, the twin brothers find themselves drawn to each other. LaBruce even has Daniel skinny dipping in a lake with the other monks while Domnic spies on him, a reflection of the Greek myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection. Their meeting provides another parallel within the plot, more twists to this tangled family tree and the root of Dominic’s narcissism in his yearning for the missing part of himself.

“Thumbing through pictures of men in underwear, he flagellates himself in a futile attempt at his own conversion therapy.”

Unlike the yearning experienced by the characters connected by blood and family ties, however, Father Andrew’s yearning is more exploitative. It’s part of a strain of patriarchal religious oppression underlying much of the film. When Dominic, arriving in Saint-Narcisse, first asks after his mother, he’s told there’s an old woman living outside of town. Most people think she’s a witch because she lives off the land, which they associate with paganism, and has a mysterious female companion (in medieval societies, lesbianism was often associated with witchcraft). Beatrice admits to Dominic that she suspected he had survived his birth and even proved it by digging up his burial plot to find an empty grave, but she couldn’t see him because the church got in the way.

Just as the church had controlled Beatrice, it tries to control Daniel. Thumbing through pictures of men in underwear (the gateway to sexual desire for many a gay boy), he flagellates himself in a futile attempt at his own conversion therapy. The funny/poetic skinny dipping scene reflects this, too, with the monks’ behaviour veering between masculine aggression and sexual teasing. Even though we see most of the monks coming on to each other and see Daniel push off a young man he had kissed, Father Andrew later tells Daniel the other monks had complained about his coming on to them. Father Andrew’s sexuality continues to take the form of control as he ties Daniel to a St. Andrew’s cross in imitation of St. Sebastian’s martyrdom.

That sex scene manages to be queasy and funny at the same time, a LaBruce specialty. It’s hard not to laugh at Daniel’s self-flagellation or Irene’s response when Dominic reveals he’s discovered he may have a twin: “Then you can go fuck yourself.”

Even the most heartfelt scenes have a little twist to remind you this isn’t standard Hollywood-issue sentimentality. Dominic’s first meeting with his mother is truly touching, with LaBruce using slow motion at points to extend the emotionality. Yet it’s also faintly absurd. Dominic has just taken a shower in the garden and is only wearing a towel that he allows to drop as the two come together. It’s as if he were trying to reclaim what should have been their first encounter at birth. There’s also a powerful emotional connection when the twins finally meet in the woods, which is quite an accomplishment for Duval, who has to play the scenes with a body double. Then the meeting veers into sexuality.

Once Daniel encounters Dominic, his focus switches from repressing his sexuality to escaping from the monastery; when Daniel meets Irene, there is attraction. Once freed of the church’s restraints, Daniel is eager to try each new form of sexual expression he encounters. Here, too, his surrender to passion has a comical side, as someone’s jealousy gets in the way. As we laugh, however, we’re aware that Daniel’s free-wheeling surrender to polymorphous perversity is far superior to the repressive, controlling sexuality of Father Andrew.

The family unit in Saint-Narcisse ultimately comes together after years of oppression and denial at the hands of a controlling, patriarchal society. LaBruce has ended other films with a sense of connection, as when the writer studying prostitution in Hustler White ends the film gamboling down the beach with the hustler who’s served as his guide. In Saint-Narcisse, however, LaBruce focuses on an actual, if unconventional, family unit. As its members struggle through desire in search of a way to fill the emptiness inside, LaBruce’s thesis becomes clear: the only way to escape the burden of sin is to stop thinking of it as sin.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra