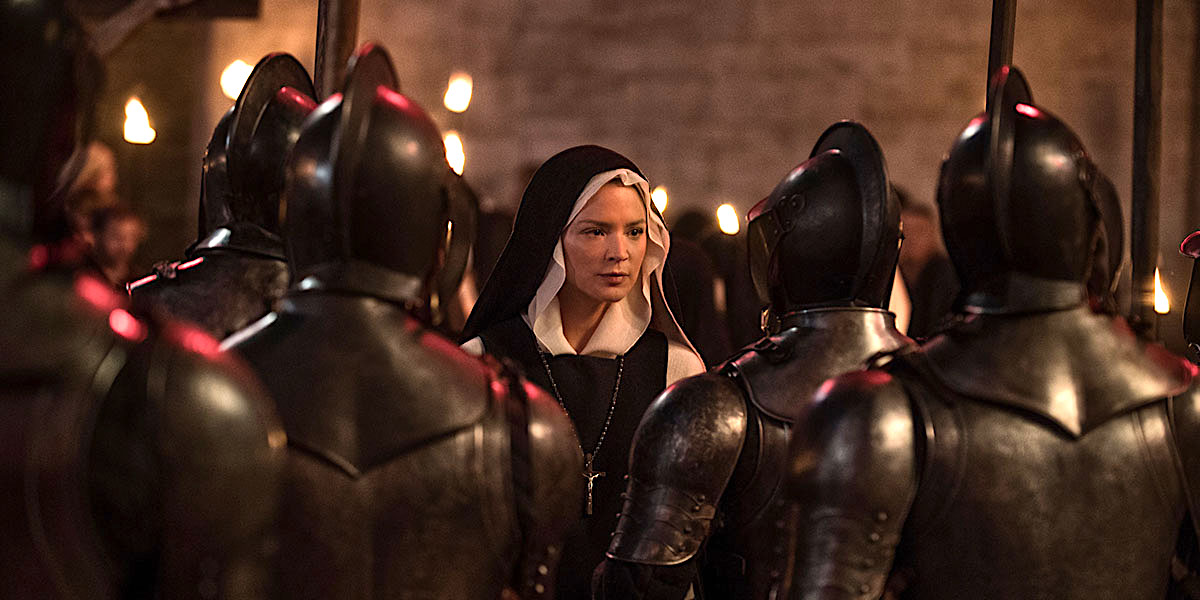

Is Benedetta really as shocking as critics say?

It’s rare to find such an unbelievable and ridiculous true story that leaps off the page and into the hands of a director able to handle the material. Adapted from Judith C. Brown’s novel Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy, the film Benedetta sounds too wild to be true. But it’s catnip for a director like Paul Verhoeven whose work often veers into the erotic, violent and psychological aspects of thrillers (see Elle from 2016 and Basic Instinct from 1992).

Benedetta Carlini was a Catholic mystic in 17th century Italy who believed she spoke to the Virgin Mary, and in religious ecstasy, experienced supernatural visions, received stigmata and claimed Jesus spoke through her. She was also sleeping with one of her fellow nuns. An absurdist story like this writes itself, but it takes a skilled writing team like Verhoeven and Elle writer David Birke to run with its kitsch and camp aesthetics to create a scathing critique of the Catholic Church. Balancing humour with a serious, thoughtful examination of religion is quite the accomplishment, proving that Verhoeven, even at 83, will never be anything but audacious.

“Benedetta is an incendiary film where female sexuality burns the powers that be at the stake.”

In this entertaining nunsploitation drama brimming with religious hypocrisy and madness, the female body is the enemy. When church leaders find themselves facing something they thought impossible—the love between two women—the bonds that suppress female sexual desire break. With all its sex and unabashed nudity, the film is more than just a Virgin Mary dildo; every decision is made with intent and not simply to shock or titillate. Nudity is thematic—it’s the whole point of the film, in fact, and moves the story forward. Benedetta is an incendiary film where female sexuality burns the powers that be at the stake.

When Benedetta premiered at Cannes, most of the reaction focused on one thing: sex. New York Times’ Kyle Buchanan was perhaps the first to note the Virgin Mary dildo and added the genius quip, “Forgive me, Father, for I have scissored” (an inaccurate reflection of the film, sadly, as it is devoid of scissoring). Another critic also described the film as a “sapphic nun fuck fest.” It’s an odd remark when you consider there are only two sex scenes. Even Variety referred to the “racy love scenes” as “reminiscent of Blue Is the Warmest Colour.” This comparison couldn’t be further from the truth: Benedetta isn’t exploitative, nor does it turn pornographic.

The gospel according to Verhoeven opens with the singing of hymns, hinting at familiarity. For much of its opening scenes, the film feels like a traditional period drama, with elegant costuming and grand, stone-built edifices. You forget who the director is until the camera pans to a performer lighting his farts on fire, reminding the viewer that we’re in for something much more theatrical—especially when the first thing we learn about the titular Benedetta (played as a child by Elena Plonka) is that she claims to speak to the Virgin Mary, who takes the form of a bird that proceeds to shit on a soldier who threatens Benedetta and her family. They’re on their way to the Tuscan city of Pescia, Italy, where Benedetta’s father, Giuliano (David Clavel), will deposit his 10-year-old daughter at a convent where she’s accepted only after he bribes the Abbess Felicita (Charlotte Rampling). This is Verhoeven’s first of many critiques of the Church, representing it as a money-hungry business pretending to be a charitable organization.

The film flashes forward 18 years, where Benedetta (played by Virginie Efira, a rare example of a woman cast in a role twice her junior and pulling it off) begins to have supernatural visions featuring a sexy Jesus (Jonathan Couzinié) calling to her as his wife. The film is at its most camp during Benedetta’s visions and moments where she’s in a trance-like state. Efira’s skillful performance plays up the theatricality of the scenes without being over the top. And the figure of Jesus challenges more traditional views of him; Verhoeven’s is an androgynous figure, perhaps to show Benedetta that sexual attraction doesn’t necessarily follow a particular gender.

Benedetta’s visions take a darker turn with the arrival of Bartolomea (Daphné Patakia). Fleeing her abusive father, Bartolomea is welcomed into the convent for a fee, of course, paid for by Benedetta’s father. The attraction between the two women is immediate and their chemistry is electrifying. In one of their first scenes together, Bartolomea is washing, and as she slips on some soap, Benedetta reaches out a hand to stop her fall. She brushes Bartolomea’s breast from the other side of a thin curtain, followed by a look of shock and confusion, perhaps from the heat coming from an unfamiliar place. Benedetta’s newfound desires trigger the next vision that finds her struggling to fight off snakes crawling all over her until a sword-swinging Jesus appears and slices away what he calls demons trying to keep them apart.

When Benedetta’s visions begin to cause her excruciating pain, the Abbess gets Bartolomea to stay by her side. Their closeness triggers stigmata, the marks of the crucified wounds of Jesus, to appear on Benedetta’s body. The Abbess, however, believes they are self-inflicted, as her stigmata appeared while asleep and not while praying. Many in the congregation believe Benedetta to be marked by the Divine. But the Abbess’ suspicions reaches a Papal representative, the Nuncio (Lambert Wilson), who launches an investigation into possible heresy, blasphemy and bestiality. The Nuncio has little concern about whether Benedetta is telling the truth or not. If she isn’t, the idea that she is attempting to be more human is beyond his understanding.

“Your worst enemy is your body. Best not feel at home in it.”

There’s much to admire in how Verhoeven shoots the female body. A gratuitous male gaze is mostly absent, the camera working to emphasize Benedetta’s point of view. When she puts her habit on for the first time, it itches at her skin. “Your worst enemy is your body,” a sister tells her. “Best not feel at home in it.”

The female body and its exploration as a tool of liberation is the most significant theme of Verhoeven’s film. Many may see the multiple shots of breasts that follow as simply titillation for the male viewer, but women are never sexual objects in this film; breasts are shown in a realistic, natural way that many would look at with disgust, like in scenes where a sister reveals her cancerous breast to Benedetta, and another where a woman squirts milk in front of Abbess Felicita. Both Benedetta and the Abbess express some level of disgust, but Verhoeven wants to show breasts in all their states.

The first thing Benedetta does when she enters the convent is kneel and pray in front of a statue of the Virgin Mary. This statue of Mary leans into vulgarity, moulded with her breast popping out of her dress, but Mary was, after all, just a woman. To 10-year-old Benedetta, whose breasts are just beginning to form, they only signify one thing: motherhood. As Benedetta prays for Mary to become her mother now that she’s separated from hers, the statue falls on top of her and she raises her lips to suck on its teat. It may bear the camp characterization of “too muchness,” but it’s a significant starting point in Benedetta’s character’s arc; how she views the female body, hers and others’, will change significantly through the course of the film.

Breasts are used to shape the story more than anything else. Benedetta is told that her body is her worst enemy, and as a result, she has never looked at herself. In one of their first scenes together, Bartolomea asks Benedetta if she’s beautiful. Bartolomea has never owned a mirror, so she has never seen herself. The nuns aren’t allowed to even change around each other. Benedetta’s oppression by the Church has led to her sexual repression, to a point where she can’t look at her own body, let alone explore it. And when Benedetta sees the breasts of another woman for the first time, they’re cancerous. That shocking image has her immediately checking her own in the reflection of a dish, making sure they don’t look like that. But her breast in the reflection is both blurred to her and the audience. She’s not comfortable looking at herself yet, so we’re not allowed to, either. This changes, eventually, due to Bartolomea and Benedetta’s evolving relationship and Benedetta’s sexual growth.

When Benedetta and Bartolomea get intimate, it’s a powerful act of defiance as they embrace their own and each other’s bodies. There’s even a bit of welcome awkwardness in their natural explorations. I think the film can be faulted, however, for not delving deeply enough into Bartolomea’s trauma. Her body was used and abused by her father and brothers, so she gives but refuses to receive in these scenes, creating tension in their dynamic that would have been interesting to explore further.

The reactions of critics gave the impression that Benedetta was going to feature sex scenes that were exploitative and pornographic. Admittedly, Verhoeven walks a fine line with the infamous dildo scene—a kitsch touch that’s ridiculous in a way, and raises questions of his intent. I see it simply as a bit of twisted humour. Moreover, it can be seen as an empowering act of gaining agency from the oppressive institution that the Virgin represents. “No miracle occurs in bed, believe me,” Abbess Felicita says in regards to Benedetta’s stigmata. But she’s proven wrong.

After the Céline Sciamma-helmed Portrait of a Lady on Fire, we saw how well stories of love and passion between women can be told when queer women are in front and behind the camera. But these stories can still be done well in the right hands and with good material. Benedetta is no Portrait, but it’s not trying to be. Sciamma showed us that love and intimacy can be explored through means other than sex; in Benedetta, Verhoeven shows that sex and pleasure carry great significance. Benedetta breaks out of a prison built by an oppressive patriarchy. And while her rebellion leads her to the flame, she isn’t the one who gets burned.

The French-language film Benedetta releases theatrically on Dec. 3 in the U.S. and Canada and Dec. 21 on VOD.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra