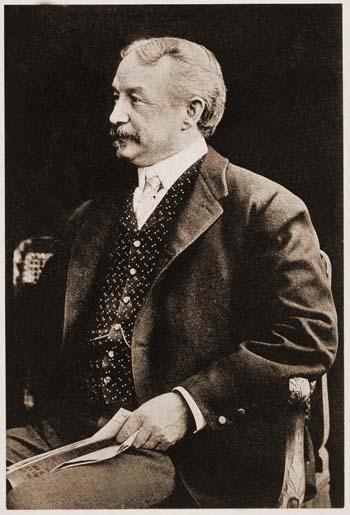

Major Archibald Willingham Butt, who died during the Titanic disaster, was thought to be one of our people.

Francis Millet died in the Titanic disaster. John Singer Sargent's famous painting Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was painted in his garden.

“Looking over the passenger list, I only find three or four people I know, but there are a good many of our people I think.”

This intriguing line comes from a letter dated April 11, 1912, penned by the painter Francis Millet to his friend Alfred Parsons. By the time the letter reached its destination, its author was dead. If April 11, 1912, seems like a reasonably inauspicious date, the events that transpired four days later are permanently inscribed on the Western psyche. The letter’s salutation instantly reveals why: “On board RMS Titanic.”

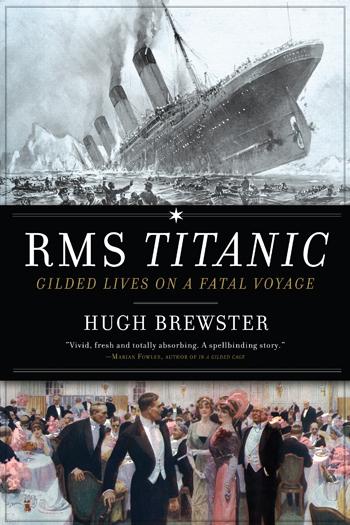

April 15, 2012, marks the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the fabled ocean liner. To mark the occasion, author, playwright and journalist Hugh Brewster wrote a new contribution to the ever-expanding field of Titanic scholarship. However, as the former member of the gay rights group Toronto Gay Action and former writer for Xtra’s predecessor, The Body Politic, is quick to point out, most people only think they know the real story of the Titanic.

“They know the James Cameron movie, and that’s about it,” says Brewster, and he should know. Brewster was involved in the publication of Robert Ballard’s best-selling book The Discovery of the Titanic and is himself the author of numerous books on the subject. He even served as a consultant on Cameron’s film.

In his new book, RMS Titanic: Gilded Lives on a Fatal Voyage, Brewster includes the stories of some of the gay men among the ship’s passenger list. Two of Brewster’s protagonists in this exploration of the private lives of the Titanic’s bright lights are Francis Millet and Major Archibald Willingham Butt, who served as military aid to presidents Roosevelt and Taft. Millet and Butt are both thought to be “our people.”

“I actually became interested in Millet seriously when I wrote a children’s book about John Singer Sargent’s famous painting Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose,” Brewster explains. “I started to research this painting and discovered it was painted in Frank Millet’s garden.”

Brewster conducted extensive research at the Smithsonian, where he discovered Millet’s passionate love letters to San Francisco poet Charles Warren Stoddard as well as the original copy of Millet’s final letter from the Titanic.

“In writing about the Titanic as a microcosm of the gilded age, I definitely wanted to write about gay men as part of it,” Brewster says. His book RMS Titanic follows the stories of several confirmed bachelors who travelled on the ship. A queer examination of the time of the Titanic’s voyage will invariably prove challenging. Before the scientific and humanitarian revolution that began in Germany in the late 19th century, homosexuality was considered something one did rather than what someone was. This lack of a contemporary understanding of divergent sexualities makes the study of queer history difficult and speculative. As Brewster notes, “letters were burned and destroyed, so gay history is about reading between the lines.”

“One of the things that always struck me about the Titanic is the coincidences,” Brewster says.

One such coincidence involves another of the Titanic’s doomed passengers. William Thomas Stead was an English journalist whose crusade against sexual impropriety and the exploitation of children led to the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 in the UK, which also criminalized homosexuality.

“At the same time Millet is writing his last letter on the Titanic, WT Stead – the man who put Oscar Wilde in prison – is writing his last letter. Maybe they met at the post office,” Brewster muses.

For Brewster, “Titanic is a universal metaphor for hubris and human folly and arrogance. In our world today, there are very few parables left; there are very few universally known stories.” And thanks to the gay-radical-turned-author, our people now have a place in that story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra