Between the 1960s and 1980s Mel Roberts took 50,000 pictures of 200 models and defined the golden boy California look for whole generations of gay men. Now, his personal collection of vintage colour prints is regaining popularity for the first time since the 1970s.

On the phone from his home in Bel Air, California, the self-described still photographer still can’t believe his good fortune at being re-discovered at the age of 83.

“I thought I’d be long forgotten,” he laughs. “I put everything away and didn’t take very good care of it because I never expected to have any use for it again.”

While obscenely chiseled bodybuilders, hustlers, and professional models were common in the magazines of the ’60s and ’70s, the men Roberts photographed were natural everyday guys. And while they were almost always friends or lovers, his first rule was that “They had to be sexy. They had to have a certain attitude. I probably turned down many more than I photographed.”

He says his models posed for the fun of it, but he paid them $25 an hour. “That was good for those days,” he remembers, “most of the guys used it to buy weed.

“I tried to make it as enjoyable as I could,” he continues. “We’d go to Yosemite or La Jolla on two or three-day trips… They got to know me pretty well before I took them out for their first shoot.” After that, says Roberts, “they didn’t mind being nude in front of me because they’d already been nude in a private situation.”

He didn’t tell them how to pose. “Most of the time I just let them be themselves,” he says. But he always told them to wet their lips–for highlighting purposes. “I was working with a flash even in sunlight,” he explains.

The approach worked. His pictures are softly seductive and his models achingly unattainable–literally. “None of them [became] professional,” Roberts says. “Very few of them ever modeled for anyone else.”

He sold his pictures through ads in the back pages of men’s magazines, eventually building a client list of “three or four thousand names,” he says. “I had customers from all over the planet.”

Roberts eventually became a homo Hugh Hefner. He had a nice home, a space-age hi-fi system and open-minded guys always bunking with him. “They had no guilt about having sex with guys [even though] most of them had girlfriends,” he remembers.

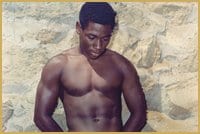

“He was referred to me by a friend,” Mel Roberts recalls of 19-year-old gay college student Butch Wallace. Wallace’s very nice butt adorns the cover of this issue and he was one of only two black men Roberts ever photographed.

“It was very difficult to find blacks to model back in those days,” recalls Roberts. “None of them wanted to admit being gay for one thing–it just simply wasn’t done for most blacks–and to appear nude in a book or magazine was mostly unheard of back in those days.”

Of course his model didn’t want to go by his real name so Roberts gave him a new one.

“Just about that time there was the ruckus with Governor George Wallace, who stood in the doorway of a university when they tried to de-segregate it,” Roberts remembers. “And I thought it’d be a wonderful kind of insult to name my model after him–for political reasons–and just added the Butch.”

But it wasn’t all Boogie Nights. Roberts had to build his own colour lab to develop his film because no one else would.

“I tried to sneak a single frame on a whole roll of film past Eastman Kodak, the only company at the time that could develop Kodachrome film,” he recalls. A few days later he got a notice from the lab saying the film couldn’t be returned because it contained a pornographic image. “I had to sign a release that the image could be destroyed,” he recalls. “Well, it was destroyed all right. They sent the roll back and what they’d done is punch a hole through the genitals on the figure.

“When I started out I knew it was going to be dangerous and that I possibly might subject myself to some form of prosecution,” Roberts says. “But I thought ‘I have to do it’ because I felt it had to be done. I was living near the Playboy Mansion and they were publishing images of beautiful women but there was nothing appropriate for showing the male figure… I fully expected to be arrested.”

He also expected visits from the cops. So, while he was doing all of his own printing, he kept his originals elsewhere in case of a raid. But when the LAPD finally came knocking they found everything because, he admits, “I didn’t expect to get raided 17 years into my career when my work was pretty tame for what was starting to come out.”

Hunting for evidence that some of his models were underage, the police raided Roberts’ home in 1977. They handcuffed him and confiscated his cameras, negatives, letters and client mailing list. Roberts recalls that anybody who happened to drop by the house was also detained and held until the police finished their search, which lasted from 10 am to almost 9 pm the next night. He was never charged with any crime.

“I felt pretty confident I’d passed inspection,” he says. “But then they came back 18 months later to see if they missed something, took everything I had and kept it for a whole year.”

He wasn’t charged then either but this time the police wouldn’t return his property. “I’d go to court. They’d tell the LAPD to return it and the LAPD would say ‘we’re still examining it,'” he says.

By the time he got everything back it was 1981. He was worn down by the harassment, AIDS was spreading and his photographs were too tame to compete with the explicit fare glutting the market.

“They were depicting sex openly,” he recalls. “There was no restriction.” Unwilling to shoot porn and wanting “to maintain some semblance of artistic value,” he eventually quit photography altogether. He lived with friends, cared for a dying parent and faded into obscurity.

Then in 1994 a film producer suggested Roberts transfer his photographs onto video (Mel Roberts’ Classic Males 1-4). Then a San Diego gallery exhibited some of his pictures and a publisher put them in two books.

Magazines began running his photographs, other galleries started showing them and collectors–like Elton John–started buying them.

He’s selling his private collection because, he says, while “there’s a market for my large prints and it’s very flattering that they sell so well, some people can’t afford them.”

Indeed, those prints that your closeted dad once bought for five or six dollars through mail-order at the back of Young Physique and Muscle Boy Magazine are now worth as much as $7,500.

As for modern erotica, Roberts says, “Some is good. Some is not so good. I enjoy seeing what’s going on and saying ‘hey, maybe I had a little input in what’s going on today.'”

But when asked about the modern gay ideal of bulked-up gym bodies he sighs and says that “It’s starting to look all the same. They’ve all got abs, pecs, tattoos and piercings. [But] it’s okay because that’s what the younger generation is doing today and it’s interesting because we’re going through another period.”

As for how the times have changed for gays since his era, Roberts, who’s been with his partner for two decades but never photographed him, confides that “People say things are much better now than they were back then. But no, they’re not. We didn’t have AIDS to worry about back then. Nobody could die from having sex like they can today,” he explains. “Because of that disease we’re not the free and simple people we once were.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra