An abusive organizer is a featured speaker at every queer protest. The domestic violence support group is run by friends of your abusive ex. What do we do when violence invades our most cherished spaces?

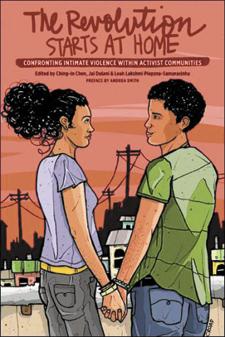

The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities is a vital new resource for reimagining ways to name and heal harm. Edited by Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, this urgently needed anthology centres on the experiences and expertise of queer, trans and gender-nonconforming people of colour (POC).

The Revolution Starts at Home began in 2003 as a zine about partner abuse and sexual assault among activists. When the zine became a book, the editorial collective expanded its scope to include documentation of activist organizations working in areas of community accountability and transformative justice — alternatives to the homo/transphobic and racist police, court and immigration systems.

As feminists of colour, the collective found that models created by white middle-class feminists were problematic because of issues including “race, class, gender, ability, sexuality and immigration status.” Seeking alternative ways of dealing with violence, including ways in which people didn’t have to leave their communities, the collective has gathered an impressive array of personal stories and step-by-step descriptions of radical transformation.

Morgan Bassichis details the history and recent reinvention of Community United Against Violence (CUAV), an anti-violence organization with a POC focus working to create safety for queer and trans people. Bassichis describes Trans Action, a project to expose and resist police abuse, and highlights how hate-crime laws can, in fact, increase incarceration and policing of poor people of colour, including poor queer people of colour.

Peggy Munson contributes a hard-hitting piece that describes the “social collusion” that occurs around abuse and disability and how people with disabilities sometimes have to choose between an abusive partner who cares for them and no care at all. Sex workers and organizers Miss Major, Jessica Yee and Mariko Passion have a roundtable discussion about the many kinds of violence sex workers experience, and about leveraging power with abusers without engaging cops, courts or prisons.

Timothy Colm, a trans man, writes eloquently of confronting an abuser and overcoming transphobic perceptions because the abuse occurred when he was a 14-year-old girl. Similarly, Orchid Pusey and gita mehrotra (of Transforming Silence into Action) highlight issues such as strictures against “airing your dirty laundry” as a survivor when your community is racially stereotyped and besieged.

The book offers no easy answers. Though many people desire justice outside the prison industrial complex, contributors acknowledge that sometimes it might be necessary to call the police or go to a shelter and that they may not have all the answers yet.

Shannon Perez-Darby warns against the oversimplification of both survivors and people who batter, and suggests a focus on holding ourselves (instead of just others) accountable. The Chrysalis Collective contributes a compelling piece on the process of creating support groups for a woman of colour and the white male activist who raped her. Their accountability process moves away from shaming the aggressor toward a radical reflection about community accountability and love. Yet the collective admits the work is exhausting and success is hard to measure.

Connie Burk, from the Northwest Network of Bi, Trans, Lesbian and Gay Survivors of Abuse, chronicles further flawed attempts at transformative justice. Burk suggests we are not yet ready for community accountability interventions, saying that they often replicate the state’s “revictimization” of survivors and leave survivors exhausted and the community divided. Instead she proposes skills classes to first build responsible communities.

A document of more than 10 years of community accountability work, this anthology is bursting with transformative poems and stories, well-developed models, vital guidelines and new questions. By providing resources and excellently written pieces about experiences and strategies, The Revolution Starts at Home offers appealing alternatives for ensuring survivor safety — and hope that more activist communities will name and break patterns of violence.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra