Credit: thinkstock

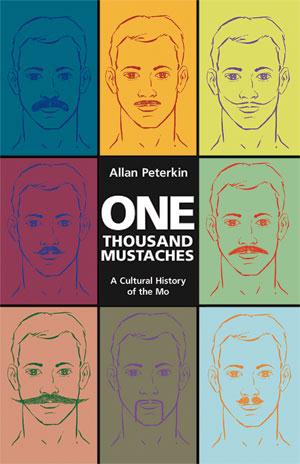

There’s not a whole lot that Hitler, Gandhi and Robert Goulet have in common. Not a whole lot, that is, beyond a place in Allan Peterkin’s new book, One Thousand Mustaches: A Cultural History of the Mo.

The book combs through some 32,000 years of discoveries, trends and events in male grooming, and despite its vaguely academic-sounding title manages to be a good bit of fluffy — or is that fuzzy? — fun.

Expect pictures and themed lists of dudes with mos. Also expect games like “Match these famous (mustachioed) actors to their movies” that, despite looking suspiciously like filler, do nothing to detract from the book’s chief strength: gathering fun and fascinating facts about the mustache. Who would have guessed, for instance, that “the first disposable razors — made of sharp flint — appeared around 30,000 BCE,” or that the world’s most expensive mustache belonged to one Merv Hughes, a 1980s Australian cricket player who insured his whiskers for more than $315,000.

Xtra recently chatted with Peterkin, the Toronto author and psychiatrist, about Dalí, Movember and the place of the mustache in gay culture.

Xtra: Why write this book? And why now?

Allan Peterkin: Mustaches are the final frontier of the facial-hair boom that started with goatees in the ’90s. Men have disparaged them ever since the ’70s because they were worn primarily by swingers, pornstars and ultra-macho gay clones, for whom they were a part of the uniform.

Men today, both gay and straight, are confident enough to grow a playful ’stache and can handle any assumptions people may make about it. Nowadays we have Movember each year, numerous mustache-growing contests and endless websites and clubs, like the American Mustache Institute, which encourage free-flowing follicular expression. The (postmodern) pomo mo is always a conversation starter!

One Thousand Mustaches is filled with fun facts about the mustache. Any favourites?

Mustache hair is the fastest growing on the entire body! Also, policemen in many precincts in India are paid extra to grow a mo, because it looks virile and powerful.

You touch briefly in the book on the esteemed status of the ’stache in gay culture. Can you take me through the rise of the ho-mo?

Many famous gay men, like Tennessee Williams and John Waters, have had trademark mos, but they’ve been the exception. The Castro-clone ’stache became a gay signifier as part of a hyper-masculine ’70s uniform, along with military haircuts, tight jeans and bomber jackets. This macho expression successfully countered cultural stereotypes of gay men as being effeminate and also became a part of the leather and SM communities. Some postulate that the ’stache disappeared for a while partly because the average Joe didn’t want his face to be read as gay or bi — not because he was homophobic, but because he didn’t want potential female dates to make wrong assumptions!

If the mo’s popularity is cyclical, where are we on that cycle?

Everything else has been done since the ’90s: full beards, sideburns, soul-patches and endless combinations thereof. The mo is definitely back! The last time it was this popular was in Victorian times.

Where do you see the mo going in the next five to 10 years?

It will likely peak within five and then go underground again until the next cycle.

Lightning round! Top five notable mos, on people living or dead.

Rollie Fingers, Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, Tom Selleck, Salvador Dalí.

What is it about your number-one mo that ranks it above all the others?

Dalí’s mo stretched across his face like a tightrope and he used it as a paintbrush!

Which Canadian city boasts the best mos?

Toronto college kids are rocking everything from the Fu Manchu to the walrus to the hipster crustache, but check out Winnipeg and Vancouver, too.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra