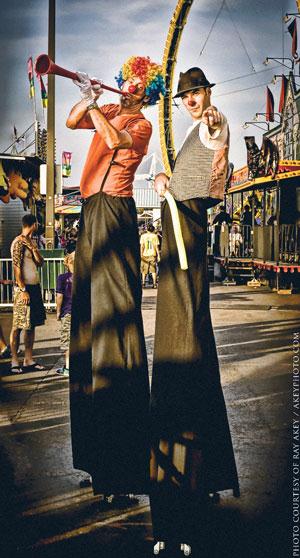

Kyle Sipkens as Tiny (right) and Mark Lefebvre as Shorty. Credit: Ray Akey/Akeyphoto.com

Kyle Sipkens always has to come out twice. Though new acquaintances rarely bat an eye when they find out he’s gay, revealing he’s a professional stilt-walker typically elicits something between a slight guffaw and jaw-dropping disbelief.

“The most common reaction is ‘No, what do you really do?’” the Toronto artist laughs. “There’s a stigma attached to street performers that we’re homeless and doing it out of desperation. But a lot of really skilled artists choose to ply their trade in public spaces, because they believe in art being accessible to the people.”

Sipkens (who co-helms Stilt Guys with Mark Lefebvre) will bring his towering presence to BuskerFest (he stands six-foot-two in bare feet). Now in its 12th year, the event gathers talent from around the globe for four days of unpredictable entertainment. Sipkens and Lefebvre’s act includes a pair of nine-foot Mounties, a double Elvis and an oxymoronic duo of giant leprechauns.

“Working outdoors means relinquishing any control of lighting, background noise or even the crowd,” Sipkens says. “I had a drunk woman decide to wrap herself around my legs once, and there’s the occasional heckler. Mark’s been knocked over, but I’ve managed to survive without any serious accidents.”

It was, however, an accident that Sipkens become a street performer at all. Raised on a chicken farm in Wyoming, Ontario, he was focused on a career in classical theatre when he entered the University of Windsor’s acting program. A movement teacher was restaging a dance film she’d made as live performance, and when Sipkens inquired about a role, she promptly informed him he’d be walking on stilts.

“It set the tone for the rest of my career, because my first response was, ‘No, what am I really doing?’” he laughs. “But it turned out to be a really useful skill to learn. Nine years later it’s how I make my living.”

Sipkens’ other period of undergraduate self-discovery didn’t go as smoothly. Raised in a highly conservative Christian family, he struggled with his sexuality until finally coming out his first year away from home.

“I knew who I was from a very young age, but I’d convinced myself it would pass,” he says. “In a world where the idea of being gay isn’t even a possibility, you’ll do anything to try to make yourself feel normal. I had to leave home to realize I was already normal and it was my thinking that was off.”

He found a supportive peer group, but his family was considerably less understanding. When a cousin attending the same university outed him, the whole gang trucked down to Windsor to stage an intervention.

“Having the family you grew up with yelling and crying and doing anything they can to turn you into something you’re not is definitely hard,” Sipkens says. “But it helped me to find the strength within myself to not need their approval. I hope they’ll come around at some point, but I’ve realized the onus is on them to change their thinking, not on me to change who I am.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra