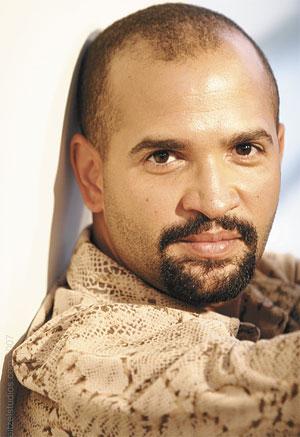

You can’t talk about Berend McKenzie’s play without discussing its title. And that’s exactly the point. Based on his experiences growing up black and gay, nggrfg (subtitled Would You Say the Name of This Play? for its Toronto run) explores two words that have been hurled at him throughout his life: nigger and fag.

Although these words have been with McKenzie since childhood, it took a pair of closely timed pop-culture moments for him to consider them as the basis for a show. The first was in late 2006, when Seinfeld alumnus Michael Richards called a heckling audience member a nigger at a West Hollywood comedy club. The second, in spring 2007, was when conservative harpy Ann Coulter called former US vice-president Al Gore “a total fag.”

“The way those incidents were reported said a lot about our culture’s relationship to those two words,” says McKenzie. “When talking about the Richards tirade, the commentators all had to say ‘the N-word’ instead of nigger. But in talking about Coulter, they had no problem using the word faggot on national television. As a black gay man I felt this disconnect was something that needed to be talked about further.”

The pair of incidents led to a larger mainstream news discussion on the notion of banning both words from popular speech, an idea McKenzie finds problematic.

“I’ve been called those things my whole life,” he says. “If we’re going to ban words, does that mean those of us who’ve had these experiences can’t tell our stories? It’s a way to invalidate the histories of oppression, racism, homophobia and slavery, rather than keeping them open for discussion.”

Stimulating cultural dialogue around the terms and the histories attached to them is a key focus in McKenzie’s work. Getting people to actually say them is an important first step.

“When you go up to the box office and ask for a ticket, it means you have to say those words out loud,” he says. “It forces people who are fundamentally afraid to even say them to confront all of the preconceived notions and histories of discrimination associated with them.”

Charting McKenzie’s life from age seven through 39, nggrfg traverses his darkest moments and his path to personal acceptance.

Moving back and forth in time, the audience hears how a skipping rope he took to school was used as a weapon against him and how his childhood doctor said he should be punished for chronic bed-wetting because “black children come with issues.” McKenzie also touches on the challenges faced by an actor not “black” enough to play the array of gangster, pimp and rapper roles available to him.

Staged in a stripped-down style (the set consists of just a table and chair) the work is both an act of autobiographical storytelling and a means of provoking discussion.

“Homophobia, racism and bullying are the major focus, but people don’t need to be black or gay to connect with the story,” he says. “If you’ve ever felt like an outsider, you’ll understand what the character is experiencing.”

Growing up in highly conservative and decidedly white small-town Alberta, McKenzie found little support for the discrimination he faced, even within his own family. As the only child of colour adopted by a white family, he was left to fend for himself. Though his family’s strong Christian faith was part of their choice to adopt, it was also a barrier to their acceptance of his identity. He fled both home and school at age 16 after a group of students caught him in a drunken grope-fest with another boy at a party.

“The student council had a meeting about it, and the next day the president told me that I shouldn’t come back to school because they couldn’t guarantee my safety,” he says. “Everyone turned their backs on me, and all the friends I had steered clear.”

Given his experiences, McKenzie wanted to present the work not only in conventional theatres, but also in school settings. He’s happy the work has sparked discussion and helped birth several gay-straight alliances in schools around the country. To those who oppose the groups, he has some choice words.

“What are you afraid of?” he asks. “I’m sick and tired of hearing people say they’re afraid of people trying to make their kid gay. Quit trying to make your kid straight. When kids feel like they don’t belong, they think it’s easier for everyone if they take themselves out of the equation. They should be allowed to be exactly who they want to be in a safe environment, not jumping off bridges or swallowing bottles of pills.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra