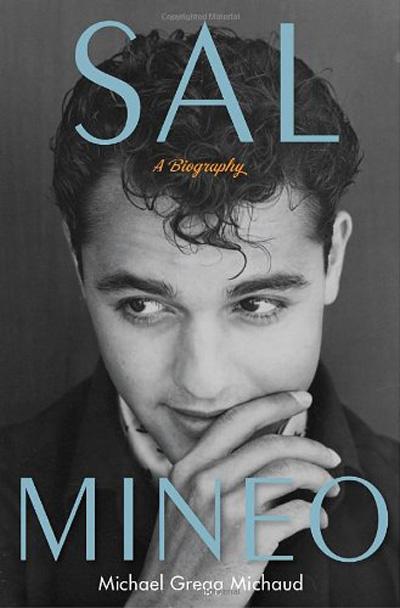

Michael Gregg Michaud meticulously undresses Sal Mineo in this revealing yet depressing biography. Admittedly, the child-star-turned-sexual-and-cinematic rebel proves fascinating. While Michaud unearths salacious detail and renders readers voyeurs of a sexually voracious bi life, he speculates little about who Mineo really was, even while backing his claims with mountainous facts.

Grounding readers at every stage of Mineo’s story, Michaud begins in the Bronx in 1939. A child of Sicilian immigrants, Mineo was a young tough constantly changing schools. He entered dance school at age nine upon insistence from a talent scout. Dancing kept him out of trouble. He progressed to acting. Mineo’s proverbial big break, the 1955 film Rebel Without a Cause, ignited his teen stardom.

A rehearsal for Rebel proved prophetic. Co-star James Dean suggested that Mineo look at him as would Natalie Wood, Dean’s girlfriend in Rebel. Director Nicholas Ray, knowing Dean was bisexual, encouraged Mineo’s infatuation with him. Ray’s alchemic directing continued on set, birthing an iconic film with an indelible gay subtext. The sensitive Plato, Mineo’s character, became arguably the first queer teenager of the big screen.

The nascent 16-year-old was a pawn in a greater game just as he would become a cog in the machine of Hollywood, although Mineo attempted to break the rebel mould for years, typecast as a young tough or a soldier-terrorist-gangster-laughable-Native-American type. Later Mineo developed a lurid taste for scripts and roles with peccadilloes, including the subjects of pimps, drug dealers, rape and sexual politics.

Michaud relies heavily on interviews, dates, film titles and media coverage, a staccato beat often bordering on tedium, until page 208. Girlfriend Jill Haworth kicks open Mineo’s closet door, catching the 35-year-old bedding his buddy Bobby Sherman. “But he didn’t stop,” she said. “He kept going at it.” Rumours of Mineo’s sexuality circulated. He found serious work even more difficult to procure, predominantly because filmmakers saw him as an embarrassing relic of the 1950s.

The biographer reveals many of the star’s actions – how Mineo accepted his first lesson in queer sex from his hairdresser, coerced an 18-year-old into a threesome and spent money like water – but little about his motivations. At times, the beats between timeline references are telling. Where did this overgrown kid’s hyperactive energy come from?

Clearly, Mineo, once free of his domineering mother and a family dependent on his earnings, wanted rebellion. He found it in living for the moment. Without a proper childhood, something Mineo often lamented, he perpetuated a prolonged adolescence. Mineo never learned to manage money; his mother was his manager until his 20s. Likewise, Mineo never cooked for himself. In later years, his former housekeeper took care of him pro bono. Mineo also pitched scripts he surely must have known were too trashy for financial backers.

Readers may not feel they know Mineo any better for all his struggling for serious roles and juggling male and female bedmates. Like Freddie Mercury or Jack Kerouac, the restless Mineo longed to do his craft and find an elusive free love. He found companionship in Courtney Burr III. Their rocky open relationship reflected Mineo’s inability to stay with anyone for long.

Michaud reveals much of Mineo but perhaps not enough. An unanswered riddle remains at the heart of this biography, perhaps because he stuck too closely to facts and resisted their analysis. Was Mineo simply a victim of child stardom, a bed-hopping Peter Pan, or could he have pulled up his boot straps and gotten on with things, in his own bi way?

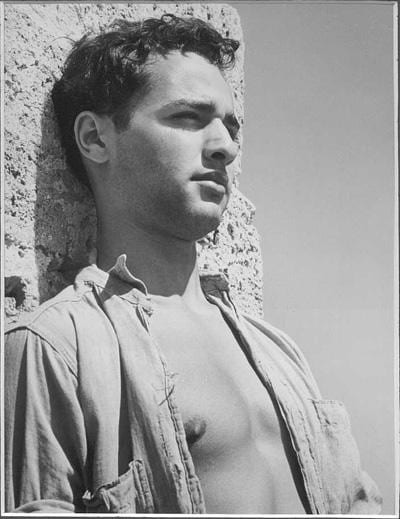

Check out Mineo in this clip from the 1965 film Who Killed Teddy Bear?.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra