creatures of ecstasy, we have risen drenched from our own

wet grasses, reeds, sea. turned out, turned inside out, beside

ourselves, we are the tide swelling, we are the continent

draining, deep and forever into each other.

–from “Touch to My Tongue”

Since the publication of her first book in 1968, Daphne Marlatt has carved out one of the most distinguished careers in Canadian letters.

In recognition of her achievements as both a writer and a mentor to younger writers, the author of 24 books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, was made a member of the Order of Canada on Oct 6.

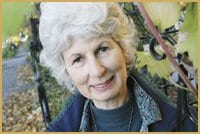

A lithe, soft-spoken and extremely centred woman of 64, Marlatt has also been known to scare people off.

“An interviewer came up to me after a reading I did recently in Ottawa and said, ‘You know, interviewers are scared of you,'” Marlatt says, sipping Chinese tea at Seto’s, a breakfast joint off Commercial Dr and Broadway.

“‘Scared?’ I said. ‘Why?’ ‘Well, because your writing is very difficult.'”

Difficult is indeed a word often used to describe her work. Certainly, readers looking for grammatically conventional sentences and overused poetic devices should look elsewhere.

Marlatt’s style, often a cross between poetry and prose, can perhaps best be described as organic, dictated less by school-taught syntax than by bodily rhythms. Her writing style is an extension of one of the primary tenets of her belief system–that one must be in touch with one’s body.

“We don’t learn in school anything really about our bodies, how our bodies work,” explains Marlatt, a practicing Buddhist. “I think it’s to our cost and it’s to the cost of the planet that we don’t think about our actual bodies. We’re rooted, we’re still connected to everything in nature through our bodies, much as we like to feel that we transcend nature. And the more electronic we go, the more we feel we do transcend nature.”

Rootedness in the body and in nature, acute awareness of the moment-by-moment responses of the mind and the senses to the environment–these are the hallmarks of Marlatt’s highly distinctive voice:

why does the eye slide off? the mind refuse anything

more than grabbing at keys, making quick arrangements,

then tearing through the parkway across the bridge along

the Upper Levels, thinking glorious glorious morning,

everyone driving their usual cavalcade of must-do’s and if

only’s, thinking how can this be? this sudden gap.

gape. a wound that is love and not love.

–from “Seven Glass Bowls”

Marlatt’s work demands that we pay attention to every word. To read one of her poems is to sharpen one’s senses, make one more attuned to the moment.

And that, says Marlatt, is why one should read poetry. “To see how we think, how everybody thinks. To be more aware of how we’re conditioned.

“We do all this short-handing of everything, all these different aspects of our daily lives. A lot of it is shorthand, so we’re not really paying attention, we’re not being mindful of what we’re engaged in. And so, really, poetry helps you to pay attention.”

And what of the popular opinion that contemporary poetry is esoteric and inaccessible?

“Gertrude Stein said that the general public is always two generations behind in their tastes. What they like is something that they’re used to, that they grew up with as children, that’s familiar. And I think that prevents people or stops people from exploring what doesn’t look familiar or sound familiar.

“I’ve talked to people who’ve said to me after a reading, ‘This is my first poetry reading. It’s really wonderful.’ It’s just taking that step, going a little bit out of the ordinary to go and hear somebody who might be writing in a slightly different way. It’s not really difficult. It just looks unfamiliar on the page.”

While somewhat resistant of the label “lesbian feminist writer,” Marlatt nonetheless acknowledges the woman-centredness of her work. “In some ways writing took me to feminism. I began to realize quite young that most of my writing mentors were men. I’m of that generation. And my body wasn’t a man’s body. I was experiencing things differently.

“So I was writing out of a female experience, a woman’s experience, and then various friends would say, ‘Have you read this book? There’s this wonderful book of French feminist theory. Have you read this book? There’s this wonderful feminist psychoanalytic critic.’ And so I started reading all this theory, and it was very exciting. It was a very exciting moment in my own development as a writer.”

Still, Marlatt doesn’t feel as though she has to be “programmatic” about bringing her lesbianism into her writing. “I don’t feel I have to sit down and write a great lesbian epic. There are lots of those out there. It’s more the texture of a life, which happens to be a lesbian life. It comes up in my writing, but I don’t feel like I have to be a missionary any longer for the lesbian lifestyle.”

Born in Australia, Marlatt spent the first part of her childhood in Malaysia before she and her family relocated to Vancouver in 1951. The city is as significant a force in her writing as her gender.

“Vancouver is my muse-city,” she says. “Growing up in the tropics, I grew up in a landscape that is very sensually abundant. Of all the parts of Canada my parents could have chosen to move to from a tropical region, this was the best one they could have possibly chosen because it’s a rainforest, it has its own kind of sensory abundance.

“This city moves me to write about it and it’s not just because it’s still beautiful despite massive amounts of new construction going on, but because I’ve watched it change dramatically since the beginning of the ’50s when I arrived here. It’s a city of constant shift and change but its core area is limited by water and mountains so it climbs higher as its history–the history of its people, especially the poor and powerless–is driven deeper into the ground. Because it’s such a young city and one that’s been well documented in photos and witness accounts, it’s still possible to hold its history in your mind.”

The mother of one, the grandmother of three and married to counsellor Bridget MacKenzie, her partner of 12 years, Marlatt says she was “shocked” when she received news that she was to be inducted into the Order of Canada. “I’ve never received a major literary award for my work,” she says.

Validated at last by one of the highest civilian honours in the country, Marlatt says she will continue to “carve my own path” as a writer, and that she can’t really conceive of a life without writing.

“I can’t imagine living an unexamined life. I find when I go through periods when I’m not writing, I start to lose my centre… I lose my centre inside myself. I feel displaced, I feel as though life is passing me by, because there’s no time to really examine what I’m doing, what I’m in the midst of. And not just what I’m in the midst of but what we’re in the midst of. What is the shape of this life that we are living in collectively?”

print small print it small enough not

to reach all of what love says when it

reads small on the whole of the page

–from “Small Print”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra