How many fags who came of age in the 1980s have not read Edmund White’s A Boy’s Own Story? On thousands of bookshelves in Canada and the US (and in translation around the world) this candid and insightful growing-up tale holds its prominent place in the swelling wave of gay American fiction that began post-Stonewall and took us well into the 1990s.

White’s 1982 tale of a lad’s blossoming desire deliciously reiterates Freud’s conviction, long obvious, that children are simmering sexpots, bubbling with filthy urges they hardly know what to do with. The novel shines a revealing but never glaring light on the secrets of gay adolescence and the seething erotic underground of family life.

Now, with a new book about his famous uncle Ed (his second on the same subject), White’s nephew Keith Fleming takes ordinary measures to illuminate the differences between White’s life and his art. “In these pages fact and fiction have been painstakingly sorted out.” Fleming defines his narrative as, “the story of a boy who made a habit of keeping the most compelling aspects of his life a secret.” White, like most of us, seems to have had a hidden homo sex life as a lad.

Fleming notes that A Boy’s Own Story “is the work of ‘autofiction’… in which he departs most from real life.” Still, in the novel, the details of the Boy’s broken home, his parents’ and sister’s personalities and his hidden erotic life are all hugely reflective of White’s childhood reality.

The most fictional parts of Boy’s Own, Fleming reports, were attempts to make the book more “universal” by toning down the breakneck pace of young Ed’s sex life. One thing that didn’t get into the book was “regular sex he began having at 13 with adult men he picked up at a train station men’s room.” (Oh, to have access to that discarded first draft!)

Young Eddie White, like his alter-ego in the novel, was saddled with a distant, scary father, a sensual (literally hands-on) high-strung mother, and a butch and bossy older sister. In real life, seven-year-old Ed and his sister Margie were awakened late one night in their Chicago home by “declamatory” adult voices in the living-room. From the top of the stairs they discreetly observed their mother, Delilah, and their father’s mistress, Kay, confronting their philandering dad, EV, and forcing him to choose between the two of them. Without hesitation, dad chose freedom from the wife and kids.

Delilah started drinking heavily. Worse, she implied often to Eddie that the marriage troubles had begun with his birth. He took it, quite naturally, as a suggestion that his very existence was a curse on the family. On top of rock-bottom self-esteem, girly Ed was saddled with wearing the pants in their precarious new household. Mom now referred to him as “the man in her life.” Margie recalls, “If she said that once, she said it a million times.” Hapless Eddie, the cause of all their misery, was also asked to be their saviour.

With such a large need to escape reality, it doesn’t surprise to learn that Eddie was an opera queen at age 11. His sister refers to this period as Ed’s “weirdo” phase. He neglected his appearance, read voraciously and shunned company. Holed up in his dark bedroom (“real smelly from old socks and underwear”), he’d listen for hours to records from the local library. Puccini was a predictable favourite, while Mozart was judged “dull.” Harp and tap-dancing lessons rounded out his cultural queering.

EV was appalled by his son’s gayness. Adolescent Ed was sent to a sports-mad prep school in hopes that its pretentious Englishy machismo would knock the sissy out of him. White admits to Fleming that he too was hoping his “imbalance” might be fixed by immersion in butch culture. In the summers he subjected himself to weeks alone at a lakeside cottage with his surly dad, who forced him to do pointless labour such as raking an entire hillside clear of pine needles.

Fleming’s analysis of White’s youthful quirks and neurotic behaviour is utterly unsurprising: Eddie was at the mercy of gay self-loathing and denial beneath a surface of raging desire and furtive encounters – with classmates, short-lived fuck buddies and even hustlers. It’s hard to think of this as news.

Ed took part in the 1969 Stonewall uprising at the same time he was taking therapy to go straight – which casts him in the same mould as thousands from his generation. The fact that this book is about a famous and accomplished writer doesn’t, in the end, make it compelling or even especially entertaining. What it feels like is a project for literary advancement, by a young writer with talent who’s riding on the handy coattails of a generous and chatty queer uncle. Fleming’s talent (so evident in his first book about him and White) is not exactly squandered here, but it’s a very pale shadow of its better self. A reading of Edmund White’s early work will unfold virtually the same narrative, but with all the artistry and nuance that this book lacks.

* Jim Bartley writes on books in every other issue.

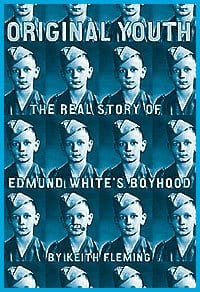

ORIGINAL YOUTH: THE REAL STORY OF EDMUND WHITE’S BOYHOOD.

Keith Fleming.

Green Candy Press.

192 pages. $19.95.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra