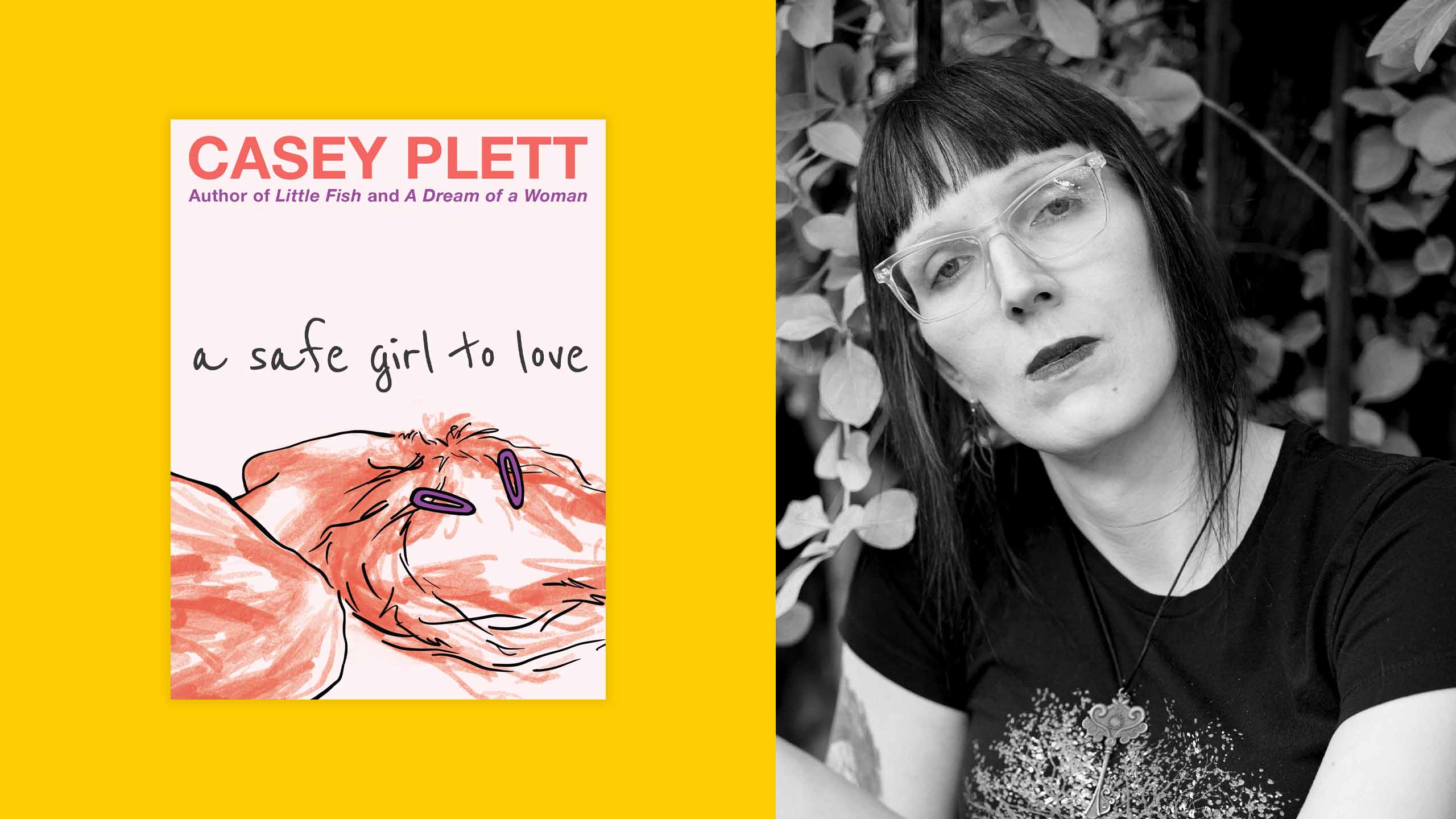

Casey Plett’s fiction is indelibly marked with the trans experience. Across her three books—A Safe Girl to Love, Little Fish and A Dream of a Woman—she has so caringly captured so many of the ups and downs that trans women everywhere face, and her clarity, exuberance and grace rank her among the best transfeminine authors at work today. And yet, in spite of how skillfully her literature zeros in on this particular territory, Plett also includes so many things that will touch anyone who has ever known what it is to be a human.

Plett’s narratives tend to move forward by erupting with little zigs and zags of action and dialogue, but then every so often they’ll pause and linger over a moment. Here, she will caringly sift through unfathomable emotional terrain—softly, as though it is an act of love. Often compared to Lorrie Moore, and grouped among trans women writers like Torrey Peters and Imogen Binnie, Plett is producing some of the funniest, most authentic literature written today. In the words of Meredith Russo, author of If I Was Your Girl, Plett is “one of the authors to read if you want to understand the interior lives of trans women.”

This month, Plett’s publisher, Arsenal Pulp Press, re-releases her long out-of-print and hard-to-find first book, A Safe Girl to Love (originally published by Topside Press and always purchasable via electronic download). Written while Plett herself was experiencing the growing pains of coming out and transitioning, the book tells very bawdy, but also compassionate, stories about trans women finding love, community and self-acceptance—in essence, making fragile accords with the world at large.

Ten years later, A Safe Girl to Love still feels as fresh and true as if it were written yesterday. First and foremost a wonderful work of literature, it is essential for anyone who wants to better understand the lives of trans women, as well as for those who are experiencing the challenges of transition, and those of us who want to remember what that vivid, tumultuous, exuberant period of our lives was like.

This book was originally published in 2014, and it has a lot of stuff in it that will probably feel pretty intense for transfeminine people. Things like the shame of trying to come out, all the frustrations of being early in transition, all the feelings of inadequacy and rejection. I’m curious what it was like for you originally working through this material.

I wrote this book very quickly. The overwhelming majority of it was written when I was, like, 25 through 26. At that time it felt very urgent for me to complete it. I wasn’t sure what my own future looked like, and I didn’t have a very positive look of what my future adult life would look like, or if I’d even have one. I’d just started hormones and changed my pronouns in 2010, so all this stuff was raw and recent. I think a lot of this book is about transition, and I wrote it in that headspace.

What’s it like looking back at it now?

Looking back a decade later, it’s been weird. Last summer I did a re-read for the first time, and I was a little trepidatious about it. It was kind of cool to find out that a lot of the stuff in there was better than I had remembered. You’re right, it is really intense; there’s a lot of stuff in there that I had forgotten about, like taking so long to shave your legs that the hot water runs out. Stuff like that made me think, like, “Oh right, that really happened, that’s so real.” A lot of the things I remembered weren’t really pleasant things. It was definitely really intense to revisit this book. Sort of in a fond way, in a really sad and achy way, I felt an enormous sadness and compassion for this person who I was.

Is there a story in here that really resonates with the present you?

With the two “instructional pieces”—“Twenty Hot Tips to Shopping Success” and “How to Stay Friends”—I really love the power that those second-person instructional tones have. Sometimes those formats are unfairly pigeonholed, like, “Oh yeah, that’s the Lorrie Moore thing,” but I think there’s a lot of power in instructing the reader to do something; there’s a lot of meat there. And then there’s the story, “Portland, Oregon” which has a talking cat—I feel very close to that story for all sorts of reasons. It’s a story about a talking cat, and I think there’s something really neat about inserting something otherworldly and just going with it. It’s interesting how some people respond to that story, like “Is she experiencing psychosis? Is the cat not real?” Those kinds of questions don’t really concern me. I’m fascinated by what happens when you introduce that kind of supernatural element and just plow forward with it.

I found it interesting that that’s the only story in the book where there’s nothing obvious to denote the protagonist as a trans woman.

I like the idea of being able to explore transness without identifying it with explicit language. One of the cool things about a story collection is that a story like “Portland, Oregon” can seem trans because of all the stories surrounding it. This story takes place in the early ’90s, and I’ve always thought of her as deep stealth. She’s really isolated, she’s really broke, she’s getting involved in the sex industry—these are experiences that a lot of trans women are very familiar with. It felt like a nice way to explore these things without marking it as trans or explicitly having that conversation.

Thinking about this question, there’s someone like Torrey Peters, who has explicitly stated that she writes for trans women, and if you read her books that’s really obvious. Do you think about who you’re writing for?

I would say a “yes, and” to this. On a writer level, I’m very attuned to the fact that I have a lot of trans women readers, and I want those readers to be served well, I want that work to mean something to them. On a craft level, I think there’s an enormous intimacy to writing assuming that everyone’s going to know what you’re talking about—otherwise, I’m going to have to write something really cumbersome, and that’s boring. When I was a teenager I would read a lot of stuff that went over my head, like, when I was 13, I read a lot of Philip Roth. So much stuff in those books went completely over my head, not being Jewish and growing up in the west, but there was still so much that I could attach myself to.

Who inspired you when you were writing A Safe Girl to Love?

The two main names, with bullets, are Miriam Toews and Imogen Binnie. Miriam Toews taught me how to write fiction in a lot of ways. She writes about Mennonites, which is of course enormous, but also the craft perspective: her work is so loose and so flowy, and the voice is so strong and she really does the funny/sad thing, like, “this is hilarious and I’m also actually sobbing.” And then Imogen, well, Nevada came out just as I was starting to write A Safe Girl to Love and I was, like, blown away. I mean it was a totally devastating book on a personal level, being a trans woman writer in 2013, but on a writing level it was like, “Okay, the lights are green, let’s do this.” It was an enormous feeling of permission that opened up to me once I read that. I was also reading Chandra Mayer—fucking brilliant—I wish everyone knew her work. And Sandra Birdsell, who’s a Mennonite writer, her first two books of stories influenced me enormously.

In my reading of your work, I’ve felt like there was this progression, from where you were really centring a lot of the brutal things about being a trans woman in A Safe Girl to Love and Little Fish to where it felt like you were dedicating more space to other parts of the transfeminine experience in A Dream of a Woman.

Those three books feel very much like a trilogy to me. A Dream of a Woman felt like I was finishing up a project that I started with A Safe Girl to Love. With the latter, it’s like, here are these young trans women in very specific spaces, and what are they making of all this? Whereas in A Dream of a Woman, yes, there are still unpleasant trans lady things that those characters are dealing with, but it’s just like, well, this is the person I turned out to be and this is the world I turned out to live in, this is just what my life is going to be like. The characters in A Safe Girl to Love are grappling with those things for the first time, and that’s really intense, as it is for newly out people. And in A Dream of a Woman, maybe some of those things are still there, but it’s like, “okay, this is my life, and I want to have a life, a long life, and I want to do other things and not be worried about that stuff all the time.” It’s like that stuff is just part of the background now.

Hearing you say that really draws me to this present moment, where it feels like people are trying to take so much away from us. We’d almost gotten to this point where we could almost live like those girls in A Dream of a Woman—like you said, being accepting of the world as it’s been given to us and attending to other things besides the fact that we’re trans—and now people are actively working to take that back away.

On a lot of levels I am so sad and upset. I’m not a terribly angry person as a rule, yet I feel so enraged by the backlash. If you had told me 13 years ago that this stuff wouldn’t just be around, but this is the form it would be taking, I’d just be like, “Fuck.” But also, Cat Fitzpatrick [Plett’s co-publisher at LittlePuss Press] said something a while back that really resonated: “When I came out in 2001, people despised us. Now they increasingly hate us. This can feel disheartening, but it’s important to recognize that it is progress. You only hate what you are compelled to take seriously.”

The whole idea of progress is a weird one. Because of this backlash there are people who aren’t going to live, and that’s atrocious—there is blood on these people’s hands—but also, we’ve built stuff, we’ve done stuff and all of that doesn’t just go away. This doesn’t mean that all of a sudden everything we’ve built and done is erased. The problem with this idea of progress is that it assumes this linear forwardness and backwardness, and that’s not the case.

I wanted to give some space to the press you’ve started with Cat Fitzpatrick, LittlePuss Press, and to talk about this whole idea of having trans people being more in control of our own materials.

It’s really important for trans people to be in control of things that concern us, like our medical care or publishing our literature. I should emphasize that as much as I do believe trans people should own more things—and I really do believe that—we started this press because there are books that don’t exist that we believe should exist. I think sometimes in the book world we get away from those things, like, “does this really have to exist, like, have to exist?” Every book that I’ve written I’ve felt real urges like that—why go to all that trouble if you don’t really believe that? The first thing we did was re-release an anthology called Meanwhile, Elsewhere: Science Fiction & Fantasy by Transgender Writers [co-edited by Plett and Fitzgerald], and last fall we also just released Faltas: Letters to Everyone in My Hometown Who Isn’t My Rapist, which is amazing. And we’ve got a couple of books in the hopper right now.

What was it like to have your novel Little Fish optioned for a movie?

I always thought it would be cool to see Little Fish on the screen, but there were all these things that I was like, “Well, you’d need to do this, and this and this …” And Louise Weard, who was the one who optioned it, had answers to all these questions and also clearly got the book. I do pity all the poor souls who will have to be in Winnipeg during the winter to film it. But I do love this idea of collaboration, since writing is so solitary, so the idea of working so intensely with other people feels exciting to me and cool.

What’s next from you as a writer?

A book that I’m finishing up right now, coming out with Biblioasis, is a non-fiction treatise of a book—it’s going to be, like, 100 pages, one of those essays in book form, and it’s called On Community. It’s one of those things I never thought I’d want to write, and here it is. Then after that, there’s another novel that I’m picking at and working on, and it does feel really different from the fiction I’ve published so far. As a writer, I’m always interested in the next thing that feels urgent, like, “this is the thing I’ve got to talk about, this is the thing I need to expel.” I feel very dedicated to following that.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra