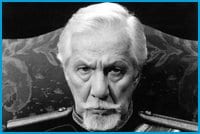

William Hutt was Canada’s greatest classical actor had a bass baritone voice and stage presence that could not be topped. His comic timing was impeccable and his comic range was immense — as were his dramatic pungency, sensitivity and versatility. Where Christopher Plummer glittered with showy flourishes, Hutt, was as the late Walter Kerr put it, “a new kind of star — a star who dazzles by being so sane.”

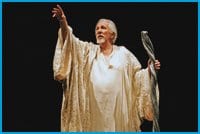

As at home with works by Coward, Chekhov, O’Neill or Shakespeare as he was in Pinter, Beckett or Sheridan, Hutt won all the major acting awards this country could offer, and he was beloved by countless fans. I rank his Tartuffe, King Lear (for Robin Phillips), Khlestakov in The Government Inspector, Argan in The Imaginary Invalid, the Fool opposite Peter Ustinov’s Lear, Bob in Murrell’s New World, James Tyrone and Prospero among the greatest performances I have seen on stage.

The amazing thing was that he became a star in a country that doesn’t want anyone to become uppity, and he did so by remaining in Canada rather than by seeking fortune and celebrity abroad. Canada Post once issued a special stamp in his honour. A bridge over Ontario’s Avon River was named after him. Soulpepper is attaching his name to its new library. Countless actors are indebted to him for his examples of technique and Canadian way of playing the classics. His cultural legacy will last so long as there is cultural memory in this country.

Who was the real William Hutt, however? Was he simply a soldier, actor and gentleman with perfect manners? His stage entrance as Wolsey in Henry VIII was a study in majestic narcissism — almost as much as some of his curtain calls were studied examples of shy modesty. He always expected his due.

“This country lacks the audacity to adore,” he once complained to me. For much of his career, pompousness accompanied dignity, but very often his wry humour prevented it from being obnoxious. After an evening where we shared his lethal martinis, he assumed a magnificent grandeur to announce: “There are two kinds of dignity: the dignity that is a disguise against being found out for what you really are and then there’s true dignity — as in my case!” Then he exploded with self-mocking laughter. At the 50th birthday celebration for Richard Monette, the former artistic director of the Stratford Festival, he made a point of wearing all his medals and orders. He explained to the guests: “I’ve come out in this vulgar display of medals because Richard was born at the time I was awarded them. And I’m wearing them in his honour.”

After a short, charming, witty speech upon receiving the Toronto Drama Bench Award at a Chalmers ceremony in 1989, he remarked to an actress friend of mine, “Now I’m going to run amok!” He didn’t, of course, but his wit could be wicked. After our final conference at his Waterloo St home in Stratford during the preparation of my biography on him, he solemnly remarked at the door, “I’m so glad it’s finally over, Keith. Now I shall never have to speak to you again!” Then he burst into loud guffaws, while I called him a tasteless old prick — before chuckling over the give-and-take.

Hutt loved gossip, but he wasn’t particularly open about his own private life — except with me during the writing of his biography. He told me about growing up in ambiguity as the middle child and second son of parents Caroline and Edward, who were steeped in Anglicanism and Victorian manners. Because his mother suffered from septicemia after his birth and was soon after pregnant with her third child, young Hutt spent lots of time with an aunt and uncle in Hamilton. He wasn’t sure where he belonged — a confusion that deepened in adolescence when he experienced the first stirrings of homosexuality. This resulted in an emotional outburst at the dinner table one night when his father was away from home: “I’m another Oscar Wilde!”

Professional counselling (by Charles Feilding, Trinity College’s then dean of divinity) followed, leading to Hutt’s finding a way to face his own secrets and reconcile his theatre craft with his sexuality. At Hart House after his war years — he was a highly decorated soldier with the Seventh Light Field Ambulance during the Second World War — his peers (Charmion King, Barbara Hamilton, David Gardner, etc) never knew about his private life. It wasn’t until he played a bejewelled androgynous Pandarus in Troilus and Cressida at Stratford (years after repertory work with the Mark Shawn Players, the Niagara Falls Summer Theatre, the Canadian Repertory Theatre, Crest and Canadian Players) that Hutt was released from anxieties about his psyche.

“I began to think like a woman, and just before I went on during the opening night I suddenly took a deep breath and said, ‘I’ve got tits!'” These tits were well covered for his Lady Bracknell in The Importance Of Being Earnest directed by Robin Phillips, but he did wear a turban with a single, tall feather standing erect. Phillips insisted on the sexual connotation: “That feather is a clitoris, and if that quivers for an instant, that would be too much!”

His private life, of course, was out of bounds to all but his closest friends and confidants. Women and men found him attractive — even more so in his senior years. He told me about his secret love affair with Louise Marleau, and insiders knew about several of his male lovers. He commented to me only on two young men — one being Larry Aubrey who had wounded him with what Hutt described as callous insensitivity. When I reported that Aubrey had been very nervous during our interview for the biography and wished to remain anonymous, Hutt cracked: “In that case, publish his name but misspell it.”

The late Eric House once related an anecdote about Hutt from the 1950s. While making up in a dressing room at the Stratford Festival, Hutt remarked, “One day I’m going to be a star in this theatre, because I’m a good Canadian, a Torontonian.”

“Come on, Bill. That’s all crap,” House responded.

“No, no,” said Hutt. “There’s no point in being in this business unless you aim for the top. One day I won’t be here unless I’m a star.”

Star he certainly was and the firmament is brighter for it. Not to see him in person while I can still hear his unforgettable voice in my head is a terrible thing.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra