There’s something so unspeakably perfect about a biracial Mexican American topping the Prince of England. It’s like sexual reparations. We have colonized the prince’s ass.

To be clear, I mean Prince Henry in the recently released Amazon Studios film Red, White & Royal Blue—adapted from a popular novel of the same name. The film is playwright Matthew Lopez’s feature film directorial debut.

RW&RB follows a fictional president’s son, Alex Claremont-Diaz (Taylor Zakhar Perez) and Prince Henry (Nicholas Galitzine) as they meet, flirt, fuck and fall in love. Chaos and hilarity ensues. International scandals abound. It’s overall an entertaining and heartfelt romp if viewed with a fair share of suspended disbelief.

Unsurprisingly, the film is the subject of both intensely serious and conversely tongue-in-cheek discussion online on topics ranging from a curious but still iconic accent from Uma Thurman (who plays President Ellen Claremont, a Democrat from Texas) to a sweet and silly coming out scene between her and her son that I think we can all envy—I mean, does anyone else want President Uma Thurman to hold them while discussing Truvada in the Oval Office or is that just me?

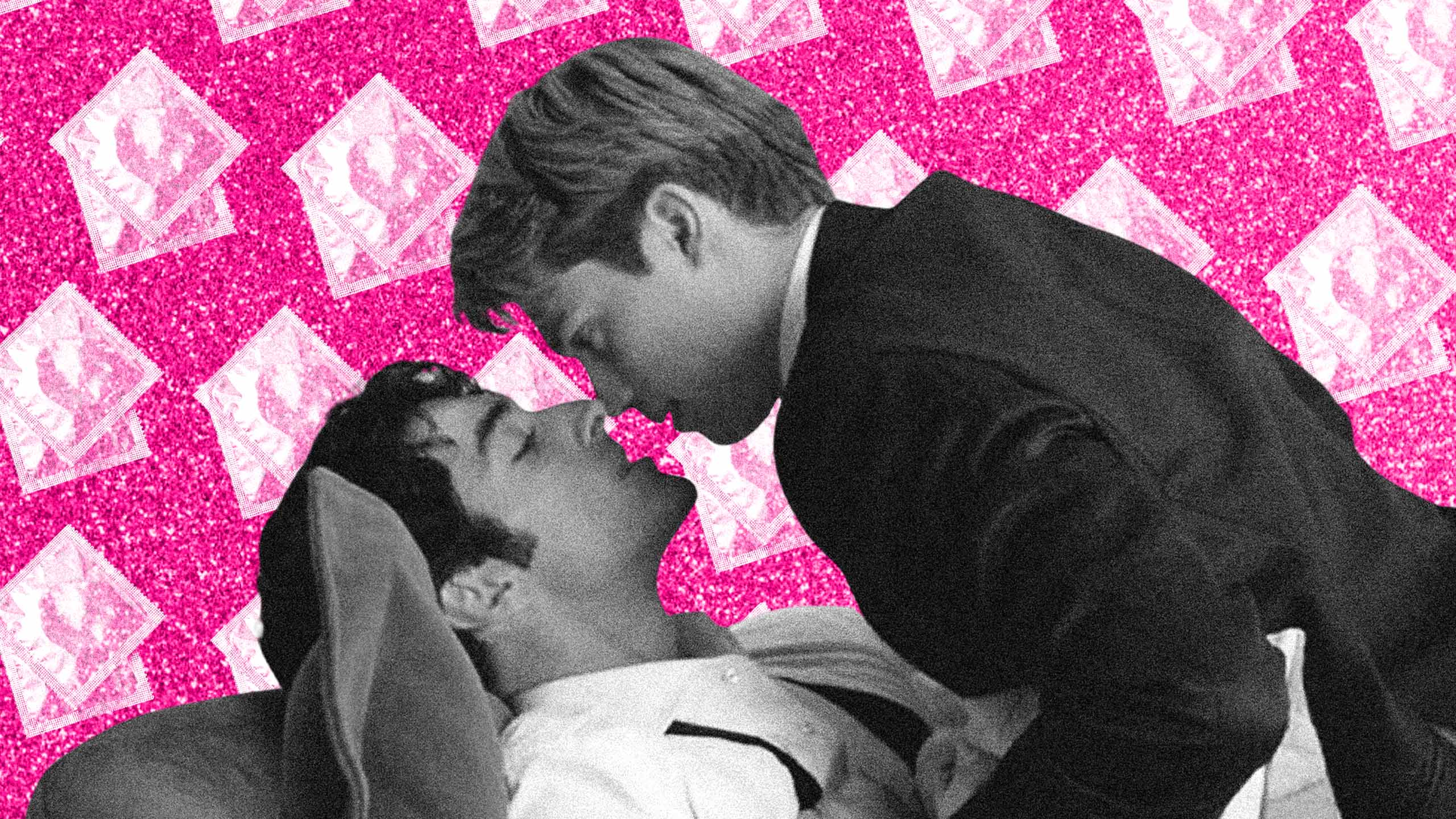

A not insignificant amount of that discussion has focused on the only sex scene between Alex and Henry, which is intimate, slow and deliberate. When I watched it, I got more Titanic than Brokeback Mountain or Bros, and I mean that in the best way.

In a podcast interview for I’ve Never Said This Before with TV host and The Rachael Ray Show correspondent Tommy DiDario, Lopez said he wanted to “show two men having sex in a way that is loving, that is connected, that is pleasurable and that is beautiful.”

“I also wanted to film a sex scene whose geography and whose physical execution makes sense to people who know how to have gay sex,” Lopez said on DiDario’s podcast. “So I needed it to both be incredibly accurate physically, and I also needed it to be [accurate to] where we are in the story.”

But it’s not the actual mechanics of the sex scene that has subreddits and social media reply chains electrified. It’s the condom wrappers seen far off in the corner during their post-sex snuggling.

As Prince Henry props himself up on his elbow next to Alex, the familiar light blue of a Trojan condom catches the eye in the top left corner. One on the nightstand, and one on the floor. (Kudos for the stamina.)

The opinions about this single scene could not be more disparate. For some, the condoms were a symbol of the importance of using protected sex even in the post-PrEP world we live in. Others found reason to poke fun at the condoms as unrealistic virtue signalling given the prevalence of condomless sex among queer men. Rich Juzwiak wrote about PrEP and abandoning condoms in 2021 for Slate—and how the phenomena started long before Gilead’s blockbuster drug came to market.

“Unwanted pregnancy is fraught, but hardly as stigmatized as AIDS has been in this country, which means that as a result of a virus that was already devastating people’s friend networks and our larger culture … populations at risk were given the additional burden of having to ’behave’ in bed, having to interrupt their flow state of sexual exchange with a barrier that also served as a reminder of the cataclysm afoot. I don’t blame them one bit for getting sick of worrying about getting sick,” Juzwiak wrote.

Lopez told Variety that the condom was an intentional choice because it would be unrealistic for the Prince of England to have a PrEP prescription.

“[Iintimacy coordinator Robbie Taylor Hunt] and I decided together that the prince is probably not on PrEP, because it would be too dangerous for him to ask for a prescription,” Lopez told Variety. “So the prince absolutely uses condoms. And because we couldn’t really effectively answer the PrEP question narratively, we wanted to also just tell the story that the prince engages in safe-sex practices and takes his sexual health seriously.”

Some viewers like Clayton Jones II, however, occupy an uncritical ground. Jones co-hosts the Men Who Like Men Who Like Movies! podcast and said he initially watched the film purely for enjoyment, but plans to go back with a more careful eye. To Jones and viewers like him, the sex scene itself represents progress in its simple, tender depiction of queer intimacy. The pregnant pause as Henry holds his knees back, the closeness of their lips, their tightly clenched hands.

Rather than focus on the condom of it all, Jones said it’s particularly groundbreaking to see such slow, tender intimacy between queer men in film.

“I thought it was really intimate,” Jones tells Xtra. “It showed the connection, just all the close-ups and their hands and being unsure of how to go about it. And I just thought it was really honest and sweet, even without being super gratuitous.”

It’s apparently so rare to see queer men have sex face-to-face that it’s sent straight viewers fleeing to the internet for answers. The fact that something so simple as missionary challenges heterosexual conventions of queer sex shows us both how far we have to go, and the power of real depictions of queer intimacy in film.

Gregory Phillips II of Northwestern’s Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing is also quick to note that what precedes condoms is usually a private, intimate negotiation between partners—one that may not necessarily be ripe for film. Phillips directs a program at the institute aimed at improving the health and well-being of LGBTQ2S+ people.

“You’re not going to go into all of the thought process behind all their decisions because there’s a million reasons why they might want to use condoms,” Phillips says. “There’s all these other scenarios you can think of about why somebody would want to use condoms that you don’t get by just having it in the corner in one scene.”

And as Phillips and public health activist Kenyon Farrow points out, the idea of safe sex in and of itself isn’t a universal definition. Farrow previously worked with PrEP4All, a national organization that works to bolster access to HIV treatment, and now works as a vice president of policy at Point Source Youth, an organization focusing on youth homelessness.

As Farrow notes, safe sex for some might mean strict adherence to condoms; for others it might be a PrEP prescription and regular checkups. For some it might not even be penetrative sex. We are a vast and varied community, and that extends to our sex lives as well.

Many viewers have also been quick to note the film’s R rating, despite the rather chaste sex scene. The sole shot of nudity in the film comes the morning after Henry and Alex have sex, when the latter is rushing to get on pants before the president’s chief of staff walks in, with a quick flash of his butt to the camera. (I’ve taken hits of poppers that have lasted longer.)

But as intimate and educational as the sex scene has been for queer and straight viewers alike, it still likely played a large role in the film’s glaring R rating from the Motion Picture Association. The rating is a conspicuous one that many, including the film’s director, argue is a sign of discomfort or outright hostility to queer themes and topics.

“If it had been a man and a woman, if it hadn’t been a gay couple, I really don’t think that scene would have garnered the R rating,” Lopez said on Didario’s podcast.

As far as critical reception, the film has lovers and haters. People who fawn over it, and others who see it as a “grim experience.” Farrow is quick to say he finds the film boring, trite and, most important, a far cry from realistic depictions of queer struggles and success, particularly given the past few years in the U.S.

“If you have two very wealthy queer men representing literally the heads of state of two global superpowers, you don’t actually have to deal with the fact that we’re still more likely to be homeless, we’re still being stabbed and attacked on street corners,” Farrow says. “We still by every economic measure, generally, fare worse than our straight counterparts. But you can suspend all of that for you know, this, you know, kind of fairy tale.”

And though their opinions of the film differ wildly, Farrow, Phillips and Jones all agree that the criticism around the film exemplifies the problems with creating media for queer people, and what happens when you’re desperate for quality representation.

The queer community is not monolithic, and neither can be a film about and for us. No sex scene will depict all the ways queer men have sex. No coming out experience will be universal enough. But that hunger that queer viewers feel for content that represents their experience is the byproduct of an entertainment system that has up until recently left them to the margins.

And when you’re fed scraps, you’d still like them to taste good, right?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra