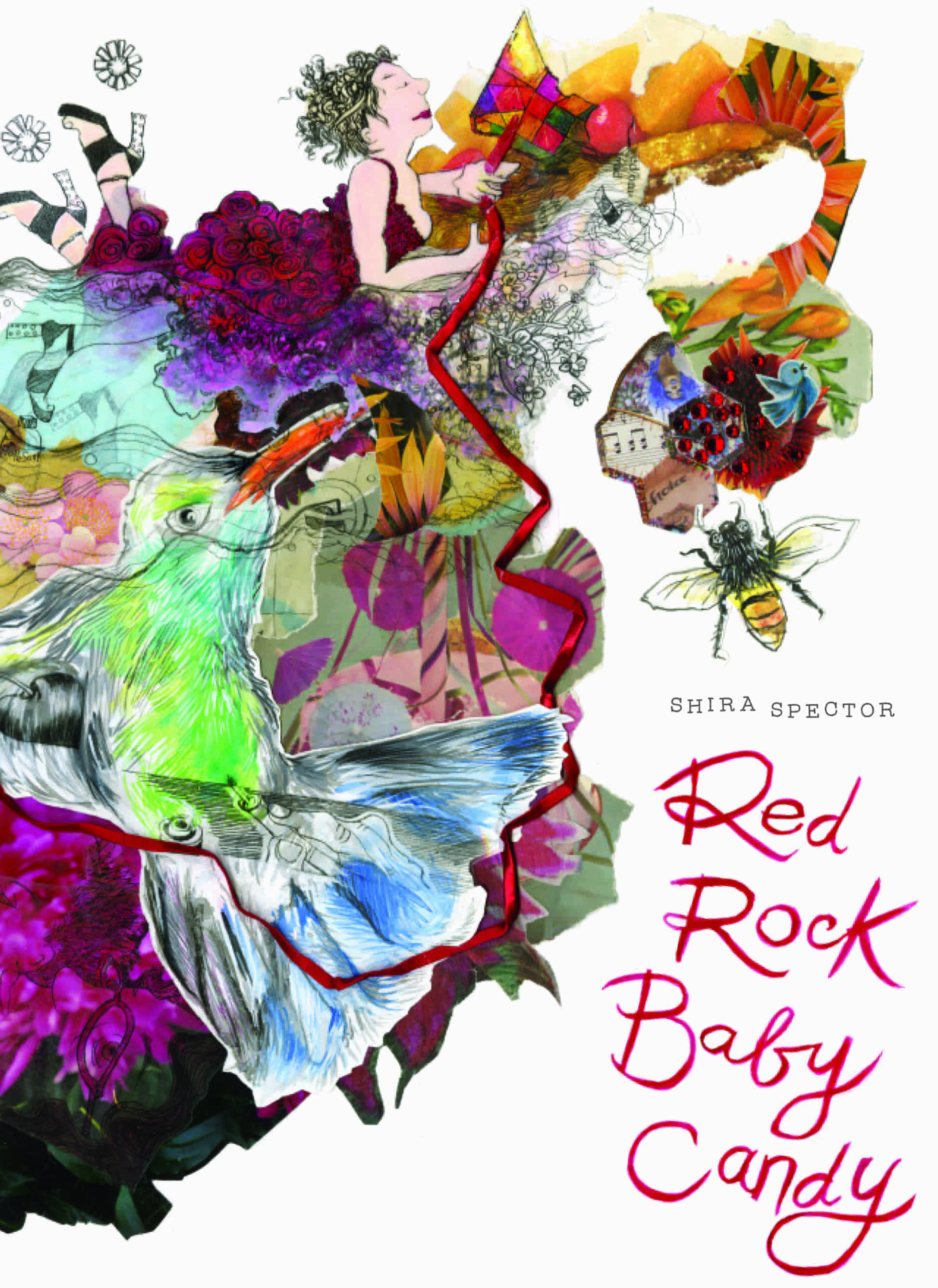

A self-described “infertile, high-femme, low income, non-biological Jewish mom, dyke drama queen and ectopic pregnancy survivor,” Shira Spector’s debut graphic memoir, Red Rock Baby Candy, is surely unlike anything you’ve seen before. The book is Spector’s exploration of miscarriage, infertility and queer parenting, all while simultaneously coping with the death of her father from cancer. She pours her soul into the explosive pages—unique patchworks of poetic text and vibrant images that move far beyond the conventions of any standard graphic memoir.

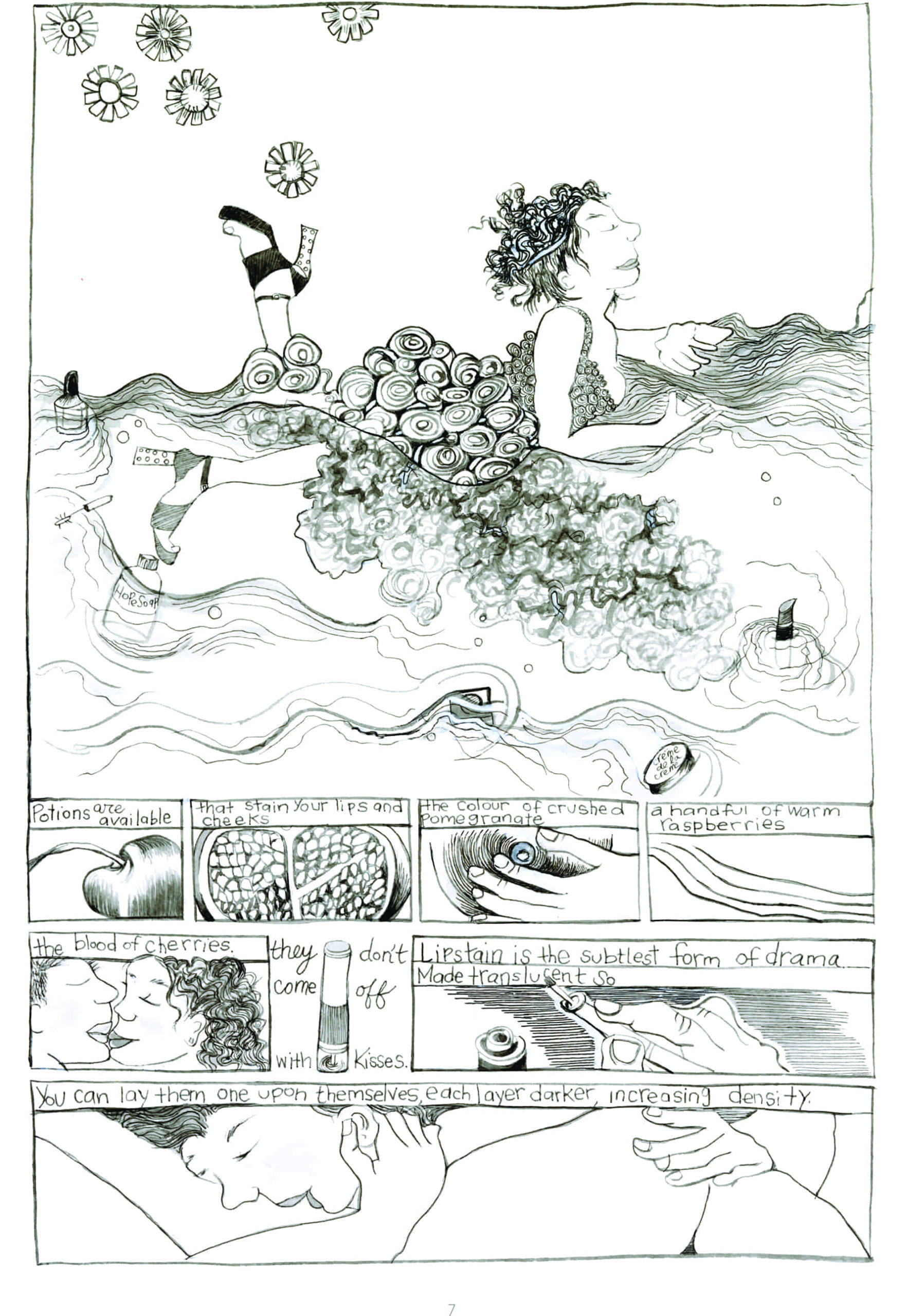

Every page is striking and feels like its own work of art. Each screams with energy, pulsates with pain and portrays a deep and powerful story of a woman who is determined to find her way to the other side of grief—and who dares to feel some joy along the way.

Toward the end, Spector writes that “the best cure for pain is speaking.” It is clear that this book, 11 years in the making, becomes her way through it all.

Spector juggled parenthood, jobs and life’s many other distractions while remaining steadfastly dedicated to bringing this book to life. She produced some pages while crammed into the backseat of a moving car, and others while sitting on the leashes of two barking dogs as a repairman worked on her house.

The book may be about grief, but when speaking to Spector, it is impossible not to feel joy. Her exuberance for her work is contagious, her passion for the story unbridled. When I spoke with Spector over Zoom, it became clear her biggest wish for this book is that others might see themselves in it, that it might show them a path through their own pain—or at least help them see that they are far from alone in feeling it.

Why was it important to you to tell these painful stories, and why did you decide to do so all in one book?

I had so much grief that had landed in my lap that I felt compelled to process it, and the way I process things is through my art.

The book took 11 years to make. Over that time things were happening in my life. My kid was growing up and turned into a teenager with his own sexuality and gender identity. It felt like everything going on needed to inform the story.

That process really helped me see not just the intersections between cancer, infertility and pregnancy loss and what it is like to deal with these two different kinds of grief—it also helped me see what else was connected to everything. I’m glad I got to dig underneath the initial grief and figure out all those other things.

Eleven years. How does it feel to be finished?

Amazing. I’m super excited to be here. It feels like I’m inviting everybody into my house. I’ve built this really bizarre house, and I’m like, “Come on in, there’s lots of really weird stuff to look at.”

What was it like to explore these really painful experiences, and to publicly share them?

I spent 11 years making this really safe space for myself where I would just go to my drawing board and work it out. I cried making a lot of those pages. I’ve ripped pages. I felt my way through every single page.

I hoped for an audience, but I didn’t spend a lot of time imagining this. I tried to make it with everything I had.

You have an extremely unique way of storytelling. It feels almost as if you’ve invented your own medium. How did you come to create this form?

Because I come from a textile background, I really didn’t know how to write a novel—but I did know how to make a quilt. I treated it like patchwork. What really fascinates me is juxtaposition and richness and layering and embellishment, so I approached the writing in that same way.

“I believe all art making is a relationship with the thing you’re doing. It has its own voice, its own needs and wants.”

I was listening all the time to this story and what it was asking me to do. It sounds odd, but I do believe all art making is a relationship with the thing you’re doing. It has its own voice, its own needs and wants, so I listened. Sometimes, it was like, you know what you need to do? You need to rip up a bunch of ’50s cookbooks and then put them back together as a cake that’s giving birth to a hummingbird.

I really scared myself when I would take those kinds of risks, but at the same time, I could identify that there was a power there; I think there’s power in the places we fear, and there’s power in risk.

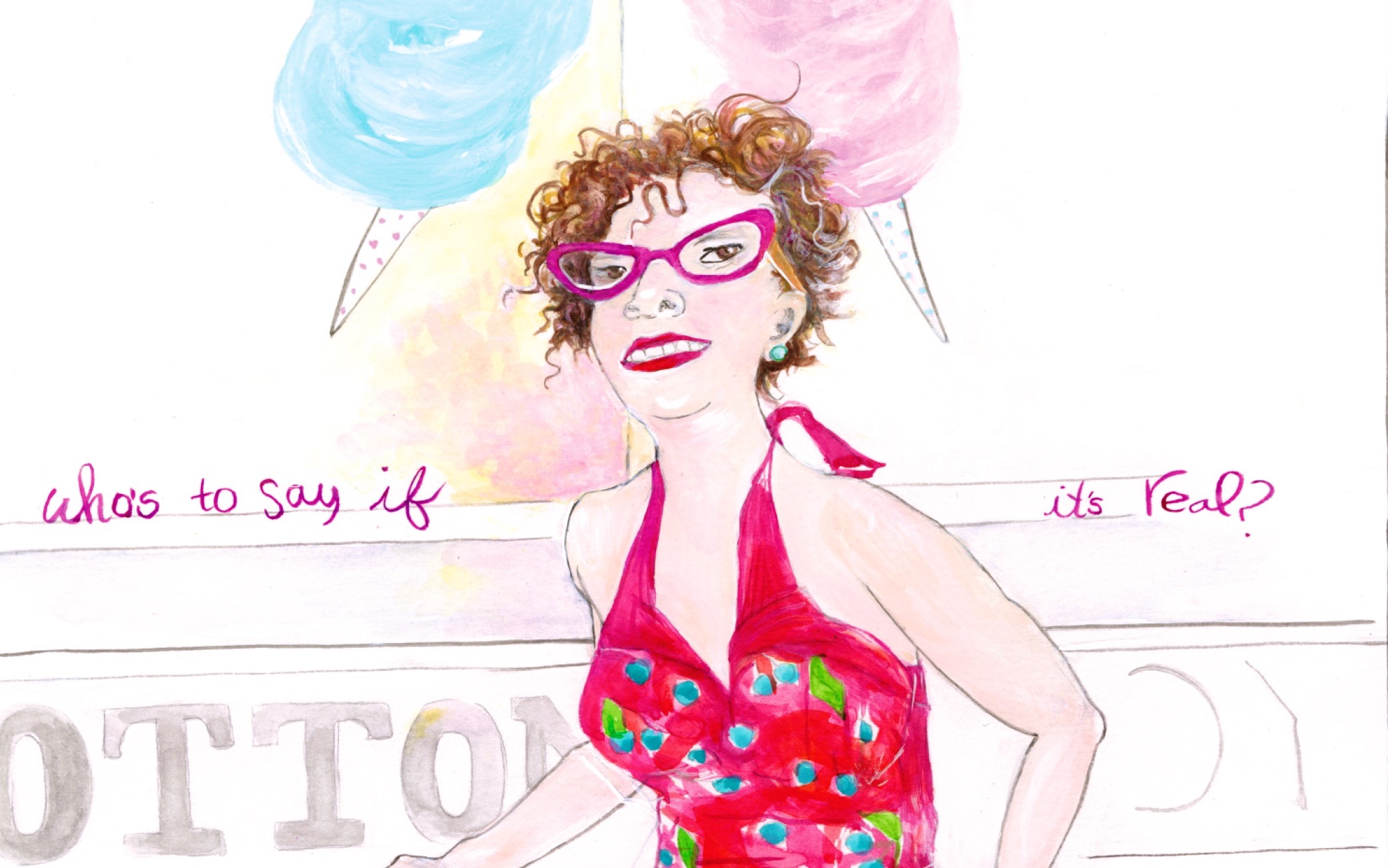

You use colour very symbolically in this book, especially fuchsia, a colour you write you are “grieving in.” Why is fuchsia such a powerful colour for you?

The colour ties into my identity as a femme, and also my identity as a girl. I was born in 1968. Pink was the colour of love to me. My parents threw it all over me.

Then I went through this whole time with pastels being really vital to me in the way I dressed when I was a young teenager and wanting to look like a freaking Love’s Baby Soft perfume commercial. I wanted to look innocent and soft. Those were the messages I was getting in the early ’80s and late ’70s about how to be a girl.

Then the colour pink evolved for me. To me, femme is fuchsia; for me, femme is taking all these things that were thrown on me and hurt me and made me feel not good enough and just throwing them back in everyone’s face with a whole bunch of sass and fire—and pointing out the whole thing is a freaking construct.

So the difference between pale pink and soft pink and fuchsia to me is the difference between the femininity I experienced as a teenager and my femme identity. Fuchsia is like a power colour to me. It’s like double thinking about what is handed to us and what you can do with it.

Credit: Zoë Gemelli

What do you most hope queer audiences take from this story?

I started trying to get pregnant in the middle of this big gay baby boom. Lots of LGBTQ2S+ people were trying to have babies and there was a lot of shiny, happy, “Look at us! We’re just like you! Don’t worry our reproductive organs are working fine!”

That’s understandable. Positive image stuff happens because people have had the experience of not being able to start families because it wasn’t safe or of having our children taken from us. So it was inside of that that I had this weird intersection of having this child that my wife gave birth to, so I had a baby while I was experiencing not being able to have a baby.

I was kind of swimming around this shiny happiness and when the miscarriage happened for me, and I just wanted to be with my people. I wanted to talk to other dykes.

There was this double silence. There was a silence around infertility in general; nobody talks about it until you talk to somebody one-on-one, and then they’ll say, ‘Oh I had several miscarriages and so did my aunt and so did my friend.” That was weird for me to think there was so much quiet, and so much extra quiet around queers.

So I hope LGBTQ2S+ people see themselves somewhat. I hope everybody who has gone through infertility and grief feels seen and feels like there’s company in this book and also that there’s a way through it.

In most public descriptions of you, you boldly list your identities as a queer, infertile, Jewish, mother. Why is it important for you to ensure people know who you are right off the bat?

Part of it is my age and coming out in the time of identity politics. I probably reflexively am like, I’m a God damn Jewish dyke!

I think, partly, it has to do with being femme and being invisible all the time. If I don’t tell people I’m gay they’ll just assume I’m not. I don’t want that to be lost. The whole idea of our stories being able to be incidental is lovely. The idea of, this is a story of infertility, this is a story of grief, is a beautiful thing without it having to be a gay story of infertility and grief. At the same time, I want my people to find me, and I want the specificity of what I’m talking about.

It’s not everybody’s story, but there is no one story for everybody’s experience of infertility. But I think we’re hearing more from people on the margins about what it’s like to traverse these things. I just hope we can keep flooding the world with the multiplicity of our stories. The more people speak from everywhere, it will be less necessary for me to say I am the following list of things. But for now, I’m pretty proud of those things, and I want them to be centred.

Red Rock Baby Candy by Shira Spector is published by Fantagraphics.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra