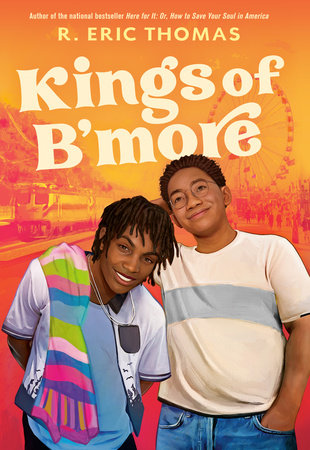

Just in case you thought R. Eric Thomas was already busy enough, with three plays premiering this spring, a truly sweet and refreshing new young adult book, Kings of B’More, hitting shelves this month and recurring gigs working as a television writer for shows like Dickinson and Better Things, you should know that the bestselling author is also moving house.

Credit: Courtesy of Penguin Random House

As you would expect from an award-winning humorist who digested the news daily for years over at Elle.com, Thomas can see the joke opportunities in every situation—even an interstate move wedged in between opening nights.

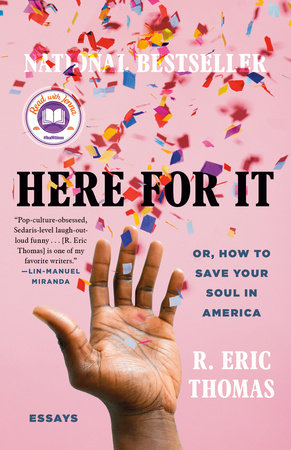

The bestselling author of Here For It: Or, How to Save Your Soul in America, a beloved Moth host and storyteller and NPR contributor, this deliciously nerdy queer smartypants has fingers in many pies. The impact of his work in the literary arts—as a Black queer essayist and playwright—has been considerable, earning both critical praise for his fresh, funny observational writing style and also the quiet valour of seeing his book shelved or stacked in the Zoom backgrounds of many scholars and celebrities.

Credit: Courtesy of Penguin Random House

Thomas has made unconventional choices—in tone, genre and subject—about which I wanted to hear more. I was also curious as to how in the world he was finding the time for so much new work. This spring I spoke to him via telephone from Philadelphia.

So how is this move going? Is it recent?

My whole house is boxed right now. I’m walking through, trying to find somewhere to sit.

“Honey! Have you seen the coffee maker?”

Well, my husband loves his coffee, so he got that out right away. But anything else, who knows? I think I have six million chargers and a coffee maker, plus all these boxes.

Oh yes, and the one roll of toilet paper, and one lightbulb that you’re carrying from room to room. [Eric laughs and groans.] I’m very excited to talk to you about all of these projects, but it’s so many projects, Eric! How does this happen? Can I get an oral history of how in the world?

Honestly, it’s largely because of the different timelines of different forms of media, crashing together with the pandemic. I started the plays years ago. One of them I started 10 years ago. With plays, you write and then you just think, “I hope somebody does this play one day.” You send them out and you wait.

Also, that first pandemic spring, my editor reached out to me and said, “Eric, I think you have a young adult novel in you.” At that point, who even knew what might happen, and so I said, “You know, sure, I’ll give it a shot. I’ll give anything a shot.” Publishing takes a year and a half from finishing a book to seeing it on a shelf. So, really, it’s a combination of me saying “yes” to random projects and COVID making all the timelines absolutely ridiculous and then everything was ready at once.

And you’re also writing for television, and other things?

That’s the other thing. The pandemic has been terrible—terrible, obviously for everybody—but television really came out of the ability to Zoom. I’ve done all my television work over Zoom, and now I’m developing a couple of TV shows. I’m working on another book of essays, as well. Okay, yes, it’s a number of things, but they’re all at different stages and so it feels … less like that, from the inside.

Mm-hm. I have had that experience. You make something and then in your mind you’ve buttoned it up and moved on. Then somebody in marketing circles back to say, “Now it’s time to tell people all about your beautiful new young adult novel.” And you think, “Um … yes! It’s about, uh, young adults!”

The other day, someone did a really great and really thoughtful blog interview with me about the book. She had just read it, had just finished it that morning. I finished this book years ago, my brain isn’t as plugged into it. This interviewer had the most wonderful, in-depth questions and connections with the book, and I just thought, “This is great! But I also feel like I’m taking a quiz that I haven’t really studied for.”

So, what have you studied for? What’s top of mind right now?

I think a lot about “What are we trying to do in the theatre?” I’m trying to put queer people and people of colour into comedic formats that feel familiar to us. Not “Oh, we’re normal! Look at us having these normal issues!” But so much of going to the theatre and consuming media in general—for people of colour, for queer people—is about using our empathy to envision ourselves onstage. Characters are not very often designed to look like us, sound like us, be like us. My idea is, what if you don’t have to use that empathy? What if you could actually see yourself in these people?

Revolutionary.

Yeah. It is. That’s also kind of the project of the young adult novel. One of the things I was seeing in the young adult space is a lot of #blackboyjoy or “carefree Black boy,” but I didn’t want to do that just to be doing it. For me, everything always has some amount of political aim, and the political aim of creating a romp between platonic friends, to make the central relationship this platonic love—featuring two Black queer characters—is for me, a kind of freedom. It’s not the same kind of freedom that Ferris Bueller had—they’re Black and queer. They have different requirements around what they can do in the world. But there is still the meta project of the book, to propose ways that boys can find themselves free in America today. I started to wonder, “What if these people were on a journey to be happy? How do you take them on a journey to be happy?” You’ve got to present some problems for them. And then help them solve them.

Mm-hm. I feel like we’ve moved very fast from “You are required to display the ways in which you are downtrodden at all times so that we can consider you acceptable” to “You are required to display the ways in which you are magical at all times”?

Yes. It’s never ever that simple. For me the best experiences of going to the theatre have always been, to quote Steel Magnolias, “laughter through tears,” It’s Dolly [Parton, as Truvy Jones] who says, “Laughter through tears is my favourite emotion.” For me, I’m less interested in, “Oh, we have to show the suffering, we have to see our own suffering reflected. We have to teach the public about our suffering.”

But I’m also not interested in “we have to be joyful because the world is hard enough.” I don’t think we have to do anything. I’m interested in creating experiences that feel like emotional dilation. They open you. You become more receptive, more willing. You’re laughing, and that opens you up to a whole wider range of emotions. So many times that we are at a movie or watching TV or in the theatre or reading a book and we come across characters that might be seen as other, and there’s this flattening of their experience, or their inner life, because the project is always, “Remember that we’re human!”

I think that’s important and that’s a first step, but other people have walked that road. Now, I and others can take the next steps down that road. I want to make sure that I am doing my best to create emotionally and psychologically complex portraits of people, even if they require an audience to do a little bit of work.

I like where this is going; say more?

This isn’t a one-to-one comparison, but in my memoir, Here for It, there are a lot of different stories about my life, and experiences I’ve had of intersecting experiences of Blackness and queerness and growing up Christian in America. One of the things that people often remark on is that I don’t include a coming-out story in the book. Yes, that’s intentional. I wanted to challenge a reader to still see me as a full and complete queer person who’s gone through a whole journey, without having to sort of open up that particular vein. Because it really has kind of become shorthand for, “What trauma built you?” Which is a great conversation for a second date, but it’s not the way I wanted to walk into the world with my book.

Do you feel like people are interested in doing that work? Do you find that people are ready to meet you at that place in the work? And I guess the follow-up question is “Which people?” Which people are willing to and ready to stretch their artistic or empathetic faculties to meet you?

I do think that more often than not, people have been willing to do the work. I especially think if you go on the journey —the journey of the book, or go on the journey with Kings of B’More, the young adult novel, or with the plays—that you get to the end and then maybe you still have questions. But different questions. It’s fascinating, though, it always comes up a little bit. I’ll be at a talkback and someone will ask: “Can you explain this very basic thing about the family structure or about whatever?” And the way I read that is: people really struggling to disregard the part of their brain that has been programmed to believe that they need this mezze platter of trauma to understand a character they view as “other.”

Do you hate it? I should ask a more neutral question: how do you feel about it?

I think these questions—they don’t come to me as argumentative. More often than not, they come to me as really confused. People think they need to know this information, about someone’s trauma or their downtrodden-ness. One of the great joys for me is to say, “Good news! You don’t!” This isn’t me being combative. I always say, “I’m not trying to be a jerk.” I’m trying to say that this will actually enhance your understanding of the work if I don’t tell you, if you are able to meet the people as people.

Okay, so where else are you subtly upsetting people and their expectations? More creative disruptions please.

Well, with Kings of B’More, the way young adult fiction is structured, particularly with gay characters, I find that there’s an expectation that it’s going to be about love; it’s going to be about romance. Which is great. I was a fully grown adult before I read a book where two queer people fell in love. I think the first one I read was Simon vs. the Homosapiens Agenda.

Never before that?

Obviously I’d read, you know, Maurice and Giovanni’s Room. But they sit in this place that isn’t just carefree love, it is just as much negotiating very hard things with society. But Kings of B’more is not about falling in love. For me, part of the project of this disruption is reminding people, “Oh, it’s very important that we find love, if we want to find love, but it’s also very important that we find each other, that we queer people find community and homes and a sense of belonging and someone belonging to us also. Sometimes that’s less initially—I’ll say “palatable”—for large swaths of audience.

So the thing I always have to say is, “Look. I can give you 90 recommendations for books that will give you that feeling. This book is particularly interested in something else. They’re going to be okay. Not because they will live happily ever after as partners, but because they have built the tool, which I believe that so many queer people need, that is to find each other, to see each other in their queerness and to show up for each other. That’s going to save them. That’s going to save them for the rest of their lives.”

So that’s what they need to see.

Yes. I’m not as interested in what other people want to see as I am in what my communities need to see. Sometimes that can be confusing to people who see us as the other, as this mystery, but that’s okay. They can catch up. They’ll like it; it will be fine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra