Babak Salari says the more time he spent in Cuba, the more powerful the bond felt. Sarari, a Montreal-based photographer, began travelling to Cuba over seven years ago, both for pleasure and to capture images. But as his research grew, Salari, an Iranian-born refugee who fled his country in 1982, could sense the strong connection between Cuban and Iranian cultures.

“Iranian culture is a homophobic one,” he says. “The president there denies everything. I felt very personally connected to the culture in Cuba. This subculture is largely one you don’t see in Cuba. I felt this very strong parallel between the two communities.”

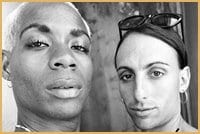

Salari became more and more drawn in by his subjects, almost 100 of which are printed in his new book, Faces, Bodies, Personas: Tracing Cuban Stories (Janet 45 Press, $30). With a powerful forthrightness and simplicity, he captures the lives of the island’s gays, lesbians and transgendered.

Cast in stunning black and white, the images are clearly empowering for the subjects, presented without any hint of apology. And the stark contrasts of black and white feel like the perfect way to reflect the contrasts of life in Cuba, a culture saturated with various political and social contradictions.

Salari, an experienced photographer who has also documented the lives of Afghans, displays a respect for his subjects that makes his photos feel less voyeuristic and thus more celebratory. And he does what outstanding photographers can do when faced with the lives of the marginalized: he makes that which has been rendered invisible visible.

“When I first went there, I was familiar with the politics of the Cuban government,” he recalls. “But I was not so familiar with the gay community there. My information was really very limited — I had seen Before Night Falls, [the 2000 film about a gay artist who flees Cuba] but not much more than that.”

As Salari spent more time there, he would meet up with one or two gay Cubans, and this would prove a crucial initiation into the entire community. From there, he would be introduced to more queer Cubans and gain the trust that would prove to be a springboard for his photography.

Salari observes a divide in the Cuban queer community, noting that life is much easier for someone who is gay and part of the Cuban intelligentsia, as opposed to, say, a struggling labourer. And while a number of artists, writers and intellectuals who are queer work quite openly there, there are still obvious restrictions in terms of government censorship.

“I know a theatre director there, who works frequently, and everyone goes to see his shows,” says Salari. “Everyone knows he’s gay, it’s not an issue for him. He gets respect.

“As well, I know a lesbian artist who explores her sexuality in her work. But if you’re a sex worker, it’s a different story,” Salari reveals, adding that he “wanted to bring both of these worlds together in the photographs.”

Salari managed to get this series of photos exhibited in a Havana gallery, saying it was well received. But not surprisingly, he indicates, there was little or no press coverage around it.

While many gay Cubans have emigrated to Canada, Salari says things are changing on the Caribbean island. “Since 2001, I sense a shift in attitudes there. I think things have opened up a bit.”

And much of this is due to a robust tourist trade.

“A lot of Canadians go to Cuba. It used to be Mexico, but many feel that country isn’t as safe as it used to be, so Cuba seems a better alternative,” Salari explains.

He also feels that Cuban culture itself is unique in the Latino world.

“Cuban culture is a mix of Latino, African and a revolutionary culture. It really is quite different from, say, Mexican culture.” This, he says, makes it an especially rich place for an artist to explore. But he also concedes that despite the emerging changes, life for queer Cubans is still often mired in secrecy. The drag culture is quite vibrant — if underground.

“Drag shows are held privately but are big. As many as 500 people will show up. The police know about them, of course, but they’re kept quiet.”

Salari was especially happy about one transsexual he got to participate in his project.

“She was quite discreet about it, but I managed to get her to open up and we developed a friendship. I invited her to the show in Havana,” Salari says.

“She blossomed as being a part of the show. She opened up, talking about how difficult it was for her to come out, to go through the process of being herself. This was one of the best stories to come out of the book,” he recalls.

Salari’s biggest hope for his book?

“I hope this will open up a window onto this unseen part of a culture. But I also hope that people can see the deep respect I have for the people I photographed in the book.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra