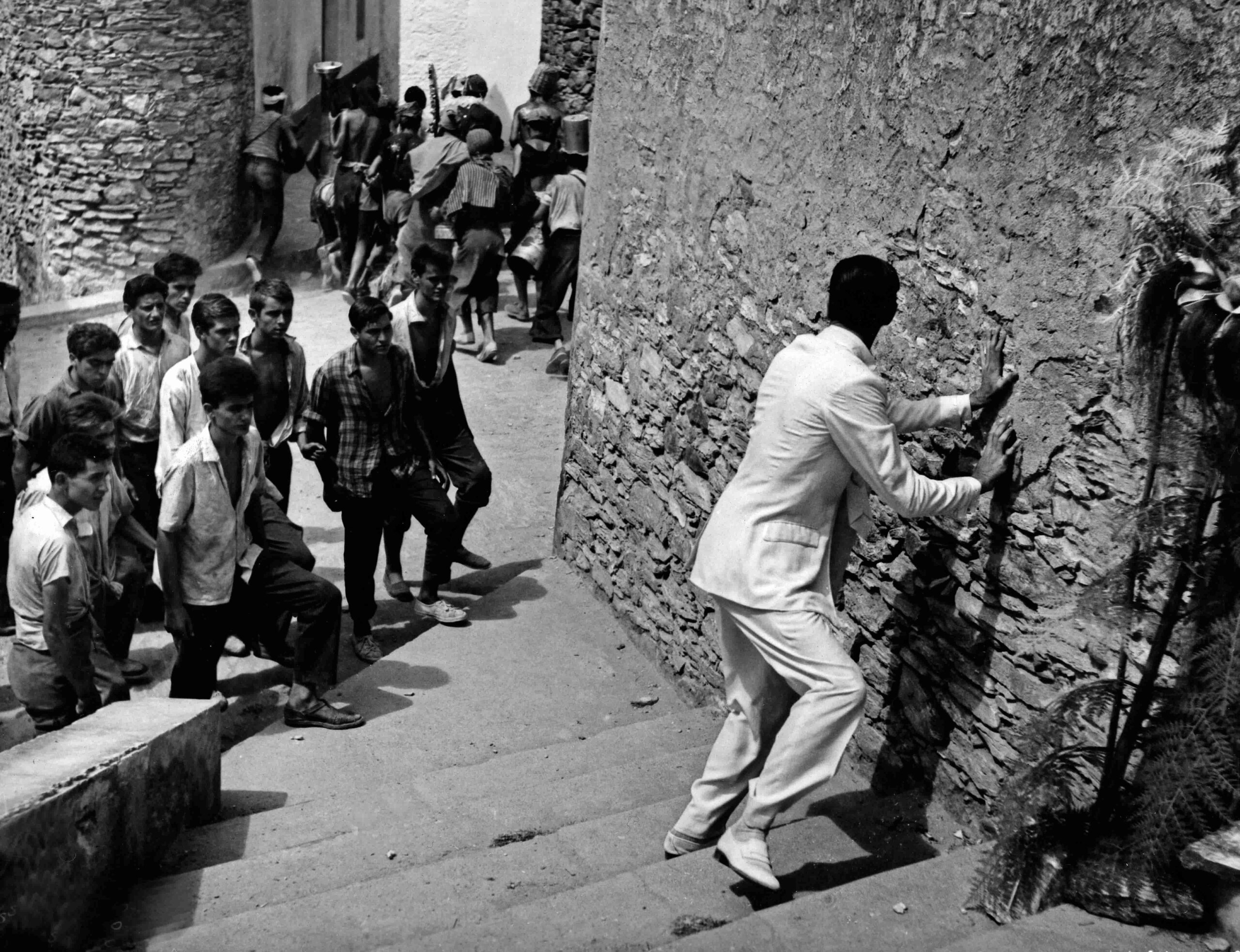

When I was 19 some 50 very odd years ago, I cut class one day to see Midnight Cowboy in downtown Philadelphia. Celebrated for its acting and John Schlesinger’s kinetic direction, the 1969 film also contained offensive, negative images of homosexuality. I wasn’t surprised. That was expected back then. In the film, Jon Voight’s Joe Buck moves to New York to sell himself to women only to wind up attracting a variety of gay men turned on by his cowboy image. At the time, I identified with the college kid played by Bob Balaban who picks him up for a quick blow job in a 42nd Street grindhouse (not that I had the guts to do anything like that). The most horrifying scene to me, however, was Joe’s tryst near the film’s end with an elderly man (Barnard Hughes) whom he beats and robs. Hughes’ character seemed almost pathetically vulnerable. Was that what it meant to grow old as a gay man? There were few depictions of homosexuals, let alone older gay men and lesbians, on screen at the time and those that existed were usually negative stereotypes like the lisping queens in 1971’s Some of My Best Friends Are…, the murderous, conflicted closet case in 1968’s The Detective or the self-loathing homosexuals in the 1970 film version of Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band.

Credit: AA Film Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Cut to 52 years later, as I caught up with Love Is Strange in 2021 (the busy life of a university instructor doesn’t leave a lot of free time for getting to the movies). The 2014 film focuses on a gay couple separated by economic problems after they marry. At one point, the younger of the two (Alfred Molina) is stuck at a party given by the male couple who are letting him sleep on their sofa. A young male stranger (Christian Coulson) strikes up a conversation with him and asks him to dinner and back to his apartment. When they arrive, I expected Coulson to turn out to be some kind of con artist at the least or a basher at the worst. I’d been conditioned to think that way by a lifetime of negative images of older LGBTQ2S+ people on the screen. But the worst doesn’t happen. Instead, the young man offers him the chance to assume the lease on a rent-controlled apartment that will finally give Molina and his older husband (John Lithgow) a home together again.

Credit: Courtesy of Sony Pictures

Love Is Strange is part of the evolution in how gay lives are depicted on screen. The negative stereotypes applied to young and old queers—the predatory homosexual, the pansy, the self-loathing suicide, the asexual expert—are dying out. In their place are a series of images of aging queers that come closer to real life. Love Is Strange simply shows an older gay couple trying to stay together in the face of economic hardships. Others, like 2010’s Beginners, explore the plight of gay men and lesbians coming out later in life. Still others, like 2013’s Gerontophilia and 2015’s Grandma, celebrate the contributions our elders have made to their communities.

According to SAGE, an organization that advocates and provides services for older queer and trans people, the senior LGBTQ2S+ population in the U.S. is expected to reach 7 million by 2030. We are a growing generation eager to see our own faces on the screen. So what do we see when we look at the big screen?

Credit: United Archives GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

Cinematic depictions of homosexuality in the U.S. were banned under the industry’s self-regulating Production Code (also known as the Hays Code) drawn up in 1930, with enforcement of the code beginning in earnest in 1934. While the anti-gay part of the policy wasn’t liberalized until 1961, there were coded depictions of queers before that. But the only overt mention under the Code was the depiction of Sebastian Venable, a stock predatory homosexual, in the 1959 adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Suddenly Last Summer.

The Code changed under pressure brought by Hollywood studios. In 1961, United Artists was planning to release William Wyler’s film version of Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour, in which two teachers (Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine) have their lives destroyed by the rumour they’re lesbians. That studio was also preparing to film Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, which includes the threatened revelation of a presidential candidate’s gay past.

Credit: Everett Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

But the ideology behind the anti-queer Production Code was hard to shake. The first films released after 1961 perpetuated the older stereotypes: predators, pansies, victims and asexual connoisseurs. Predatory homosexuals turned up a lot early on, with the senior contingent represented by the likes of Barbara Stanwyck as the lesbian madam with a yen for some of her girls (including French model-turned-actress Capucine) in 1962’s Walk on the Wild Side and Lotte Lenya as the evil SPECTRE operative in the 1963 James Bond thriller From Russia With Love. Foreign imports brought us Alain Cuny as the gay pirate who marries Martin Potter in 1969’s Fellini Satyricon, the decadent bourgeoisie in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom and, more recently, Judi Dench as the teacher fixated on Cate Blanchett in the 2006 Notes on a Scandal. Queer predators continue to turn up on screen, but more often they tend to be younger, allowing for either more physical action—as in 2006’s 300 in which the noble and manly Lionidas (Gerald Butler) is persecuted by the effeminate King Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro)—or sexual tension, as with Ryan Gosling in 2002’s Murder by Numbers.

Credit: Everett Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

The pansy stereotype dates from the silent days, and by the early talkie period, Ernest Thesiger was its principal senior portrayer. The actor, noted for his off-screen needlepoint sessions with the Queen Mother, was typecast in fruity roles, particularly in two films from gay director James Whale, 1933’s The Old Dark House and 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein. As the mad Dr. Pretorius in the latter, Thesiger provides much of the film’s comic relief with his effeminacy, his lustful glee at meeting Boris Karloff’s monster and his repeated line, “It is my only weakness.” In the film this refers to drinking and smoking cigars, but savvy viewers couldn’t help but wonder what other “weaknesses” he harboured.

Credit: Everett Collection: Alamy Stock Photo

After 1961 the pansy remained the butt of jokes in supporting roles in comedies (almost anything with Paul Lynde, for example). In more serious films, the pansies became tragic, self-loathing queens. You couldn’t laugh at them for being gay, but they still were clearly outliers in a heteronormative film world. Such pathetic roles provided opportunities for older actors like the closeted Dirk Bogarde as the doomed composer Aschenbach in gay director Luchino Visconti’s 1971 Death in Venice or the straight Tom Courtenay in the 1983 adaptation of Ronald Harwood’s play The Dresser. Bogarde’s performance has been embraced by queer audiences for his depiction of the older man’s obsession with a young male beauty; Courtenay’s character is more problematic. Norman the dresser is so pathetic—hopelessly in love with Albert Finney as the aging, egotistical actor Norman’s kept afloat for years with little in the way of appreciation—you almost wish someone would put him out of his misery.

Credit: Everett Collection: Alamy Stock Photo

Another type that developed under the Production Code was the queer expert, the aging lesbian or gay man revered for their knowledge. When Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century Studios decided to turn Clifton Webb into a star (after initially arguing against hiring him for 1944’s Laura because he was too “nelly”), he cast him as Lynn Belvedere, the waspish writer who takes a job as a nanny in 1948’s Sitting Pretty so he can research a book on suburban living. Webb was so popular he returned to the role for two sequels, not to mention a string of leading roles that sometimes paired him, unconvincingly, with a series of wives and girlfriends. Similar queer experts include Otto Kruger in Douglas Sirk’s delirious Magnificent Obsession from 1954 as the artist whose sessions teaching Rock Hudson the power of anonymous charity read like seductions, and Agnes Moorehead in 1959’s The Bat as a mystery writer who helps catch a serial killer while happily sharing her bedroom with her maid/companion (strictly for protection, she claims—back then some people actually believed her since these experts are always dealt with as in some way asexual).

Credit: Mary Evans/ Studiocanal Films/Alamy Stock Photo

When this type became openly queer starting in the ’60s, a new element was added. The expert was celebrated as part of our collective LGBTQ2S+ legacy, and there’s a hint of this in 1962’s The L-Shaped Room. Cicely Courtneidge plays a retired music-hall performer who entertains the residents of a seedy apartment house at Christmas (in male drag, no less) and schools single, pregnant Leslie Caron on the importance of having someone special in her life, as she herself did. When Caron asks if “he,” this “someone special,” performed on stage too, Courtneidge just tells her to go look at a picture on the mantle (not shown on camera). Caron’s expression makes the partner’s gender clear, as Courtneidge says, “Takes all sorts, dearie.” When the British film was distributed to the U.S. in 1963, the Production Code’s administrators tried to have that scene cut. They argued that it wasn’t necessary to the plot, a problem they rarely had with the depiction of predatory queers. That may explain why the expert role was one of the slowest to develop. One of the few major late 20th century films to feature the type is Visconti’s 1974 Conversation Piece, with Burt Lancaster as a retired science professor and art history expert.

Credit: Courtesy of TIFF

For years, the connoisseur only turned up as a supporting figure (the ballet company’s artistic director played by James Mitchell in 1977’s The Turning Point, is a rare example), until the emergence of independent film in the 1990s and a few major studio hits featuring prominent gay and lesbian characters. In 1998’s The Birdcage, the U.S. version of France’s 1978 La Cage aux Folles, the gay expert returned to a leading role. In the U.S. film, Nathan Lane and Robin Williams are not just the heads of a thriving nightclub but also, as it turns out, model parents. They would later be joined by John Hurt as the elder Quentin Crisp in 2009’s An Englishman in New York; Walter Borden as a nursing home resident in Gerontophilia; Lily Tomlin as the lesbian poet in Grandma; Antonio Banderas as a film director struggling with health issues, addiction and memories of a lost lover in Pedro Almodovar’s 2019 Pain and Glory; and Udo Kier as a retired hairdresser in 2021’s Swan Song.

Credit: Courtesy of Starz

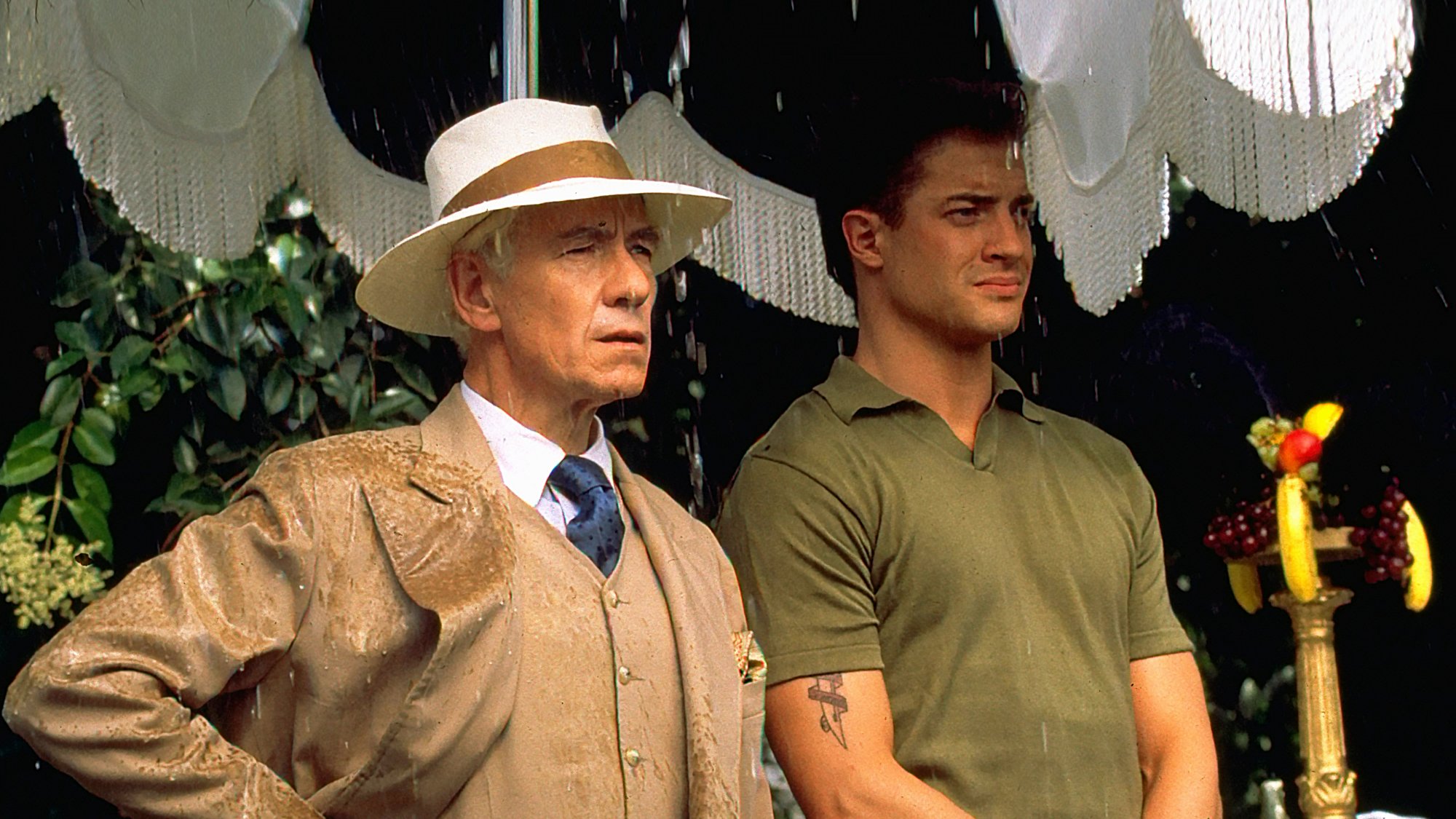

Gay writer-director Bill Condon offers a fascinating variation on the queer expert in his 1998 Gods and Monsters. As the aging film director James Whale, haunted by memories of his past, Ian McKellan at first seems a call back to the pathetic, self-loathing queens of earlier years. When he cultivates a friendship with a hunky straight gardener played by Brendan Fraser, he seems to be turning into a stereotyped gay predator. With the revelation of his true motivation, he hopes he can get Fraser to kill him since his health problems make it impossible to work in his art form, the story moves into different territory. Any pathos is generated not by Whale’s queerness but rather by the ravages of age. At the end, after Whale dies by suicide rather than trying to push Fraser to violence, you begin to realize how much his friendship has transformed the younger man; McKellan’s character emerges as a truly touching legacy hero, one who couldn’t help inspiring others even at his lowest ebb.

Credit: Courtesy of Amazon Prime

When films released in the U.S. were allowed to deal with homosexuality, coming out became a staple narrative device. Early on, it was treated as tragic—like when Rod Steiger’s title character in The Sergeant dies by suicide after admitting his feelings for GI John Phillip Law. Visconti offered a more positive, if bittersweet, view in Conversation Piece in which Burt Lancaster stars as a retired widower who becomes infatuated with a gigolo played by Helmut Berger (Visconti’s off-screen partner). As independent prouctions began offering more positive depictions of homosexuality, coming out was a popular theme in films like Donna Deitch’s 1985 Desert Hearts and 1998’s Edge of Seventeen. Older gay men and lesbians started to come out on screen, too. John Hurt in 1997’s Love and Death on Long Island was married in the past and apparently never had any homosexual feelings until he becomes obsessed with a young man. His pursuit of a vacuous young actor (Jason Priestley) is a gay comic twist on Lolita, with a lot of the film’s humour coming from the contrast between the cultured English man of letters and the star of a series of mindless teen sex comedies. In 2014’s Boulevard, Robin Williams plays a married man who has repressed his homosexuality for 50 years until one night he picks up a street hustler (Roberto Aguirre) just to talk to him and look at him, which seems a rather dreary way to end half a century of self-denial. That’s better than what happens to Albert Finney in 1994’s A Man of No Importance; in a throwback to the gay victimization of earlier years, he gets robbed and beaten when he finally comes out. What Happens Next, from 2011, is almost more sitcom than feature film, but at least the retired businessman (Jon Lindstrom) who comes out late gets a cute freelance writer (Chris Murrah) to show him some love.

Credit: Courtesy of Amazon Prime

Late bloomers also feature in the supporting casts of the 2002 Spanish comedy My Mother Likes Women, which focuses primarily on the shocked reactions three sisters have on learning their divorced mother (Rosa Maria Sardà) now has a girlfriend, and 2014’s This Is Where I Leave You, in which recently widowed Jane Fonda’s revelation of a longtime affair with neighbour Debra Monk takes a back seat to her children’s romantic problems. The most notable of the late-life coming-out subplots involves Christopher Plummer’s Hal Fields in Beginners. Plummer became the oldest Oscar-winning actor to that time for his performance as a widower who comes out to his son. Hal even gets a hot younger lover (Goran Višnjić) before dying so that his straight son (Ewan McGregor) can become a better person. That makes Hal one in a long line of queer characters—as well as Black, Indigenous and other characters of colour—who are sacrificed in the name of straight white personal growth.

Along with the coming out trope, another popular way of dealing with older queer characters is through the depiction of May-December romances. Intergenerational queer love is often a source of raised eyebrows, as when the daughters in My Mother Likes Women are particularly shocked that their mother has taken a younger lover. Gerontophilia deals with it in a more matter-of-fact manner: Young Lake (Pier-Gabriel Lajoie) just happens to have a thing for older men. After making out with his girlfriend, he cruises an older man working as a crossing guard. When he gets a job as an attendant at a nursing home, it provides the perfect setting in which to find the man of his dreams. Canadian writer-director Bruce LaBruce, known for his transgressive work in films like 1991’s No Skin Off My Ass and 1996’s Hustler White, sparks a quiet revolution here by depicting the older gay character as an object of desire. He even gets a comic spin out of the situation with scenes in which Lajoie is consumed by jealousy every time another young man speaks to his boyfriend. It’s Lolita in reverse, and as an elder queer myself I found it rather thrilling.

Credit: Courtesy of Ixion

The increase in films depicting seniors and late-life problems and relationships makes perfect sense considering that LGBTQ2S+ people, along with everybody else, are living longer and staying healthier later in life. Invariably, many of these films focus on the problems older queer couples face, since happiness doesn’t usually provide enough material to fill a 90-minute or longer running time. As with their single predecessors, the most common issue facing older queer couples on screen still seems to be homophobia. This isn’t necessarily expressed as physical bashing, though that certainly has been seen in films like Midnight Cowboy and A Man of No Importance. Rather, it takes the form of job discrimination and the heteronormative assumption that all people are straight until proven otherwise, thus rendering the queer invisible. When Alfred Molina and John Lithgow marry after years together in Love Is Strange, Molina is fired from his job as a choir teacher at a Catholic school, creating financial strains that force the two to live apart in a queer variation on Leo McCarey’s 1937 classic, Make Way for Tomorrow.

Credit: Emotion Pictures

Heteronormativity rears its ugly head in 2002’s Cloudburst in which Brenda Fricker’s divorcée has never come out to her conservative granddaughter (Kristin Booth). With Fricker’s eyesight failing, Booth rushes her into a nursing home; she’s ignorant of the fact this will separate Fricker from her longtime lover, played by Olympia Dukakis, because Booth can’t even conceive of her grandmother as a lesbian. A similar problem faces the characters played by Barbara Sukowa and Martine Chevallier in the 2019 French drama Two of Us, when the latter suffers a debilitating stroke before she can explain to her children that she’s been involved with Sukowa for three decades. Her children have no concept that Sukowa could play an important role in their mother’s recovery, and they even try to exclude her from Chevallier’s life. In the 2019 Hong Kong drama Twilight’s Kiss, neither the married Pak (Tai-Bo) nor the divorced Hoi (Ben Yuen) can come out to their families, forcing them to pursue their relationship within the walls of a gay bathhouse.

Credit: Strand Releasing

It’s perhaps a sign of progress that recent years have brought films about queer couples not troubled by homophobia. Instead, their problems are the same as those facing older adults around the world. The older lesbian partners in 2018’s The Heiresses are dealing with reduced incomes. When they run out of heirlooms to sell, Chiquita (Margarita Irun) falsifies information on a loan application and ends up in prison. More recently, in Supernova, Sam, a concert pianist played by Colin Firth, sees his happy life with Stanley Tucci’s novelist, Tusker, threatened by the latter’s dementia. As they go on one last road trip through England, they must face the fact that Tucci feels himself increasingly a burden on his husband.

Credit: Courtesy of HBO

Supernova is beautifully made, with strong performances from the two leads and a sense of restraint that puts it far beyond the typical disease-of-the-week television film. But its only gay element is the fact that the central couple consists of two males: their relationship is accepted by family, friends and pretty much everybody with whom they come in contact. When Tusker throws a surprise birthday party for Sam, all the guests are either straight or that strange paradox endemic to dating apps, “straight-acting.” In one sense, this is a sign of how far queer representation in film has come; it’s become possible to create an intelligent film about LGBTQ2S+ characters in which they legitimately seem to be just like straight people. But here’s the twist: that acceptance can come at a cost. I kept wishing effete character actor Ernest Thesiger would show up as a party guest just to remind us how queer queer can be.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra