“Who is she? Who was she? Who does she hope to be?”

When The Boys in the Band premiered at the Theater Four off-Broadway on April 14, 1968, its gay cast members and director, Robert Moore, were all still in the closet. When the 50th-anniversary revival opened at Broadway’s Booth Theatre on May 31, 2018, all of the cast members and director Joseph Mantello were openly gay. A lot has changed in the half century since the premiere of Mart Crowley’s play about a gay birthday party that goes terribly wrong. Producer Ryan Murphy’s new movie adaptation of The Boys in the Band, premiering today on Netflix, offers a fascinating, at times terrifying, perspective on both the changing nature of gay representation and the changing attitudes of the LGBTQ2 community and society at large.

It’s hardly surprising that most queer actors were closeted in the late 1960s. Few Americans at that time knew any out gay men or lesbians. Sodomy was illegal in 48 states, with only Illinois and Connecticut the exceptions; Canada wouldn’t decriminalize sodomy until 1969. In many places, including New York City, it was illegal for two men to dance with each other. Gay and lesbian characters were either tragic figures with little recourse but suicide, as in 1961’s The Children’s Hour and 1962’s Advise and Consent, or else—as in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope, from 1948, and The Detective, 20 years later—they were demented killers.

Things weren’t much better in the theatre. Between 1926 and 1968, depictions of homosexuality on stage were illegal in the state of New York under the Wales Padlock Act. The law was passed after the casts of Sholom Asch’s God of Vengeance and Edouard Bourdet’s The Captive, two plays dealing with lesbianism, were arrested for obscenity. Some gay dramatic characters slipped through, but they were far from positive representations. Before The Boys in the Band opened, one of the rare Broadway plays dealing with homosexuality was Meyer Levin’s Compulsion, a fictionalized depiction of the Leopold and Loeb case (which also inspired Rope) that treats sexuality as part of the men’s motivation for murder.

There were, of course, gay and lesbian playwrights, but they rarely wrote about queer characters. When they did, it often flew right over the critics’ heads, as with Tennessee Williams’ Something Unspoken and Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. What some theatre critics did write about in the 1960s, however, were the dangers posed by homosexuals in the theatre. A controversial 1961 New York Times article by Howard Taubman launched open season on gay theatre artists—particularly playwrights who supposedly disguised gay characters as women. In 1965, Martin Gottfried of the Women’s Wear Daily referred to Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as “the most successful homosexual play ever produced on Broadway.” In another Times piece, this one from 1966, Stanley Kauffman couched his homophobia in a plea for gay playwrights to write about their own worlds, an opinion echoed in William Goldman’s 1969 book The Season.

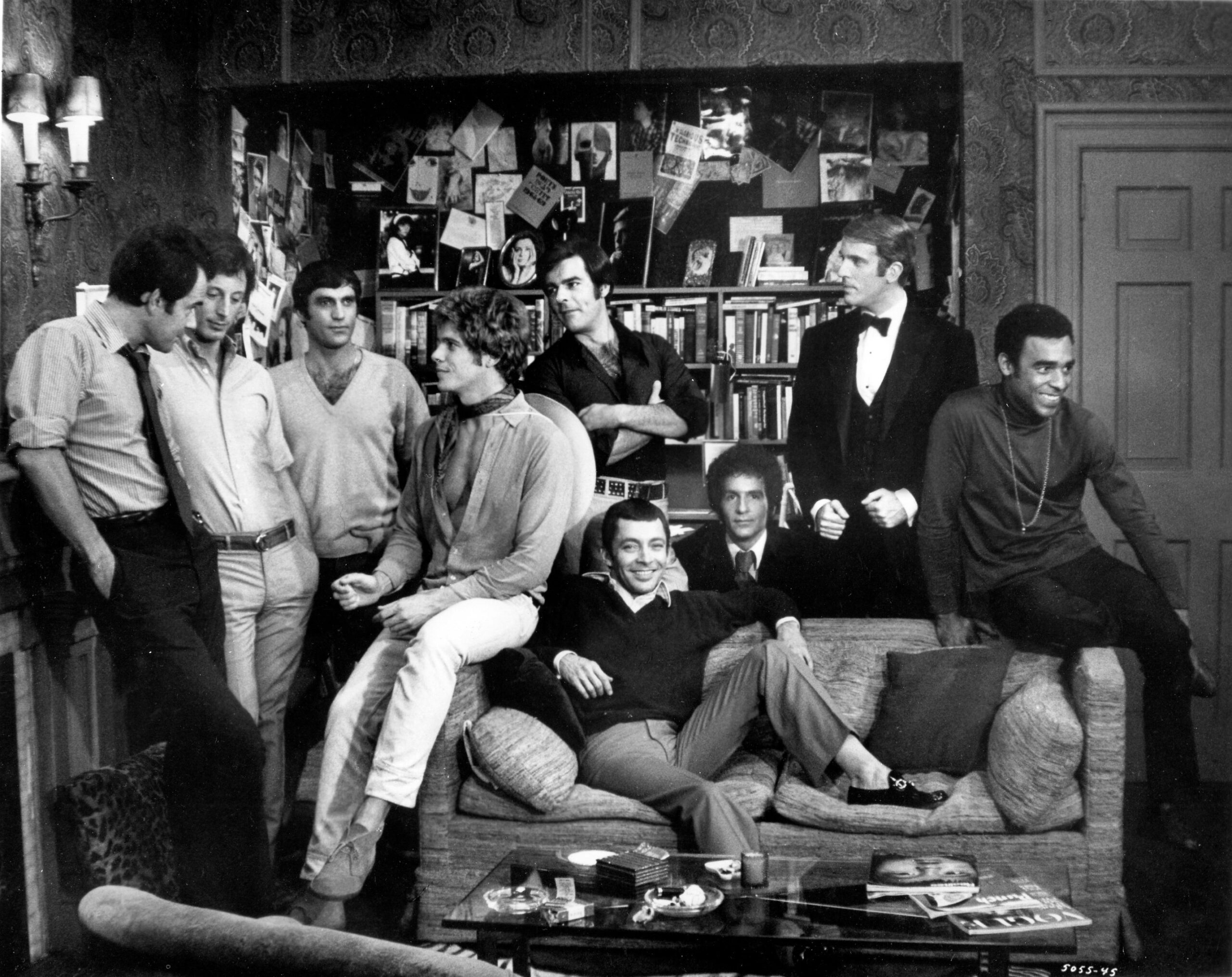

The original 1970 cast: Laurence Luckinbill, Frederick Combs, Cliff Gorman, Robert Le Tourneaux, Keith Prentice, Kenneth Nelson, Leonard Frey, Peter White and Reuben Greene. Credit: Cinema Center Films, Leo Films, Ronald Grant Archive, Alamy Stock Photo

Given the climate of 1968, then, The Boys in the Band was a definite breakthrough. Here was a play about eight gay men—none of whom committed murder or suicide. Crowley filled the play with gay humour, the kind of quips you’d hear in a gay bar. Early on, for example, the party’s host, Michael, looks at his receding hairline in the mirror and says, “There’s one thing to be said about masturbation: you certainly don’t have to look your best.” Michael later mentions that there was a time he wasn’t out of the closet, to which his friend Donald cracks, “That must have been before speech replaced sign language.” After Alan, the straight visitor, beats up one of the queens, birthday boy Harold tells the victim, “Your lips are turning blue. You look like you’ve been rimming a snowman” (a line that was a great hit with Princess Margaret when she saw the play’s London company, even though she had no idea what it meant).

The characters represent a wide range of gay types (some would say stereotypes): from the highly effeminate Emory to the acid-tongued Harold to Hank, the recently divorced man now living with his lover. At the centre is Michael, a recovering alcoholic who has internalized society’s rejection of his sexuality. His return to drinking and subsequent lashing out move the play from witty comedy to psychodrama.

Initially, the production attracted a largely gay audience, eager to see themselves depicted in a way they could consider honest. As word spread, however, more and more straight people started showing up, propelling the play through 1,001 performances. Film historian Richard Barrios has suggested that their attendance was a sign of tolerance; Cliff Gorman—the straight actor who originated the role of Emory—suggested they came to see a freak show.

The Boys in the Band was still running on June 28, 1969, the night the Stonewall Riots started. In the atmosphere that followed what’s often called the birth of LGBTQ2 Pride, The Boys in the Band took on a new identity. In a very short time, the play was viewed not as a breakthrough, but as a reflection of the negative views of homosexuality common in straight culture. Its characters may not have been deranged killers, but some of them were close to suicidal. Other criticisms cited Emory’s effeminacy as a negative stereotype and latched on to Michael’s line near the end, “Show me a happy homosexual, and I’ll show you a gay corpse,” as the antithesis of the gay rights movement encapsualted by Frank Kameny’s popular slogan, “Gay is good.” This view turned Michael’s line into the play’s single artistic statement, rather than a specific character’s response to the specific events of the play. It also overlooked the play’s many positive aspects: the ways in which the characters care for each other, for example, and the fact that Hank and his partner, Larry, who wants an open relationship, arrive at some kind of détente because of their love for each other.

That was the atmosphere in which the film version of The Boys in the Band was released in 1970. Crowley had refused to sell the film rights unless the picture was made his way. Instead of going with a major studio, he negotiated a deal with the relatively new Cinema Center Films, which kept him on board as producer and screenwriter and kept the off-Broadway cast together. His only concession was dropping Moore, who had not yet directed a film, in favour of William Friedkin, a straight director who had impressed co-producer Dominick Dunne with his television work and the film adaptation of Harold Pinter’s 1968 play, The Birthday Party.

“Reading the play as a 20-year-old college junior in 1970, I found it both thrilling and terrifying.”

Friedkin’s directing style—a punchy, emphatic filmmaking approach later on display in films like 1971’s The French Connection, 1973’s The Exorcist and the infamous Cruising in 1980—played into the hands of the play’s detractors. Many reviews complained that he had rendered the partly comic play too serious. Pauline Kael, while praising the play’s “giddy gay-bar humour,” suggested that “Friedkin, by limiting the number of actors in the frame to those directly involved in the dialogue and by the insistence of his close-ups, forces our attention on the pity-of-it-all.” Writing in the Saturday Review, Hollis Alpert described the film as an anachronism: “The attitude of the film toward its characters—that they are more to be pitied than censured—seems rather unnecessary during these ultra-liberated days.” It didn’t help that Friedkin told interviewers, “I hope there are happy homosexuals. They just don’t happen to be in my film”—a statement that made his approach to the film seem particularly inauthentic.

Reading the play as a 20-year-old college junior in 1970, I found it both thrilling and terrifying. It was wonderful to know I wasn’t alone. At the time, I had one out gay friend, a design major who was terrified to come out to the military when his draft number came up. I’d heard rumours about some of my theatre professors and one or two more advanced students, and I had a huge crush on one of them, queer playwright Albert Innaurato, who directed his early, very gay plays at Temple University in Philadelphia. But Crowley’s play also justified my own closeted situation. Michael’s self-loathing reflected the negative things my very conservative family had said about gay men on the rare occasions they even talked about homosexuality (I don’t think they had any idea that lesbianism existed). And when they talked about gay men, they usually refered to them derogatorily as “queers.”

As I moved on to graduate school and moved out of the house for good, my feelings about the closet gradually changed. Attitudes toward The Boys in the Band, as a play and a film, also softened over time. Early on, playwright William Hoffman and gay film historian Vito Russo offered more balanced views. In his 1981 book The Celluloid Closet, Russo suggested that the stereotyped Emory was more than balanced by the depictions of Hank and Larry, and that the play was “not positive, but it was fair.” In the introduction to his 1979 Gay Plays: The First Collection, Hoffman called the play more “an indictment of homosexual self-hatred” than a criticism of homosexuality itself.

The major turning point in the play’s reputation came in the 1990s with popular revivals in Hollywood and New York, as well as a 1996 reissue of the script in 3 Plays by Mart Crowley. By that time, Tony Kushner, himself a defender of the play, had successfully presented a gay villain in his depiction of Roy Cohn in Angels in America. By comparison, Michael’s self-loathing didn’t seem that bad—after all, the only person he really hurts is himself. In his forward to Crowley’s 1996 collection, Gavin Lambert positioned The Boys in the Band as a reflection of its period: “In the ’60s gay was still widely regarded as bad, or at best a neurosis, and the only genuine emotion The Boys could be allowed was guilt.”

Those shifts in reputation, along with more positive LGBTQ2 representations in film and television, helped make possible Murphy’s stage revival and his new film version, released on the 50th anniversary of the original picture. Working with director Joe Mantello and a cast of out gay actors, he offers a more positive window into the world reflected by Crowley’s play.

The 2020 cast: Tuc Watkins, Andrew Rannells, Matt Bomer, Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Robin de Jesús, Brian Hutchison, Michael Benjamin Washington and Charlie Carver. Credit: Scott Everett White/Netflix

On the surface, the biggest difference between the two film adaptations is the way they’ve been opened up for the screen. For the 1970 film, Crowley and Friedkin created an opening montage showing the various guests on their way to the party. The 2020 remake has a similar opening, though the scoring is significant. Friedkin plays his montage over the Harpers Bizarre cover of Cole Porter’s “Anything Goes,” which seems like a smirking set-up for this trip into a world unknown to most 1970s filmgoers. The remake opens with Sam & Dave’s “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” which speaks more to a sense of community (“Don’t you ever feel sad / Lean on me when times are bad”). For the new version, screenwriters Crowley and Ned Martel have also created brief flashbacks to visualize stories the characters tell about their earliest gay experiences and, most important, shots of them leaving the party. These closing shots underline a sense of community as they focus on the ways some of the characters connect emotionally after the evening’s traumatic events. They also point to a sense of survival through that community, reflecting the fact that LGBTQ2 people are often sustained through their chosen families.

“In Mantello’s hands, the play becomes a living organism, a community in the throes of breaking free from a world that condemns it.”

The way Mantello shoots the party itself also creates an important distinction from the 1970 film version. Cinematographer Bill Pope uses digital cameras, but also wanted a look reflecting the play’s period. Using anamorphic lenses, he creates a wide-screen image similar to that of studio productions of the late 1960s; Mantello makes particularly good use of that aspect ratio. After working with the cast for months on the stage revival, he has an intimate knowledge of how the play works as an ensemble piece. As a result, he doesn’t use the preponderance of single-actor close-ups that dominate the 1970 film. Instead, he more often shows the speaker in the same frame as other characters, each going through their own emotional journeys. Alan’s growing respect for Emory, whom he’d earlier derided as “a butterfly in heat,” Michael’s loss of control and Larry’s realization that whatever he has with Hank is worth keeping are all much easier to follow in this new film. In Mantello’s hands, the play becomes a living organism, a community in the throes of breaking free from a world that condemns it. Michael’s self-loathing is still there, but it’s now more persuasively balanced by the sense of survival and community that were always in the play.

Fifty years after The Boys in the Band reached the screen in a way that could easily be interpreted as a condemnation of homosexuality, it’s returned in a new, more positive form. What once was a depiction of self-loathing and loneliness is now a celebration of a community’s strength. It’s as if The Boys in the Band have finally come out of the closet and realized that gay is, indeed, good.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra