When you’re born into an Italian aristocratic family, life can be as lazy, decadent and, well, gay as you’d like it to be. But Count Don Luchino Visconti di Modrone was never one to take easy street, even when it was gilded with the privilege of being descended from dukes and kings. Instead Luchino Visconti became one of the most important and influential Italian filmmakers in cinema history – with a special place in queer history thanks to his groundbreaking film Death In Venice. The depth and beauty of his vision is on display during the Visconti retrospective just beginning at Cinematheque.

A man of contradictions, Visconti (who died in 1976 at the age of 69) lived a life of luxury, but also considered himself a Marxist, and served time in a fascist prison after allowing his palazzo to be used by members of the Communist resistance during World War II. Openly gay (his lovers included fashion photographer Horst P Horst, director Franco Zeffirelli and the star of many of his later films, German hottie Helmut Berger), he spoke rarely on the topic. But almost all of his films include homosexual characters or subtext – not to mention very attractive leading men – that would have been instantly recognizable to gay audiences at the time.

No rich slacker, Visconti also bred champion racehorses, enjoyed a career as a designer and was as renowned for directing opera as he was film – Maria Callas’ performances of Verdi at Milan’s La Scala under Visconti’s direction are considered definitive by opera fans.

It was an introduction to French filmmaker Jean Renoir (by Coco Chanel!) that set Visconti on the path to a career in film. After apprenticing with Renoir, Visconti returned to Italy to direct his first film in 1942, Obsessione (8:30pm on Sat, Jul 31) which he funded by selling some of the family jewels. An unauthorized adaptation of the novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, the film is a stunningly photographed, erotically charged tale of lust, murder and betrayal, which, although censored by Italian authorities, was a huge hit with audiences who embraced its raw sensuality and small-town realism. The director even included a gay subtext to the film, in the character of a Spanish drifter who yearns for the strapping hero and attempts to lure him away from the object of his obsession.

In 1948, Visconti followed Obsessione with La Terra Trema (8pm, Fri, Jul 16) widely regarded as one of the masterworks of Italian film and a landmark in neo-realist cinema. Shot on location in a Sicilian fishing village, Visconti employed the local townspeople as actors in this story of the economic exploitation of fishermen by the wholesalers who buy their catch at cruelly low prices. Funded by the Communist party as the first in a planned trilogy focussing on the harsh conditions of southern Italy’s working class, La Terra Trema was the only one completed. If the untrained performances verge on the cartoonish, the film is more than redeemed by its heartrending storyline and brilliant, indelible images. A shot of the village women shrouded in black, standing by the sea awaiting the return of their men is simply breathtaking.

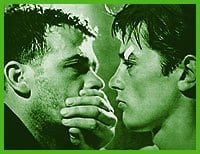

The Cinematheque program includes all of Visconti’s films, and for gay cineastes there are several worthy of particular attention. Visconti ended his love affair with neorealism in 1960 by directing Rocco And His Brothers (6:30pm, Thu, Jul 8 and Tue, Jul 20), considered one of the most important films in Italian cinema and his last to dwell on the travails of the working class. The stunning Alain Delon is Rocco, who moves from southern Italy to the big city of Milan, with his mother and genetically blessed brothers in tow. Renowned for its unflinching brutality and masterful storytelling, the film follows the fortunes of the five brothers attempting to make a life for themselves in the unforgiving city. Rocco becomes a successful boxer (precipitating the inclusion of many barely-clothed locker-room shots) under the tutelage of a gay promoter, who’s both attracted to and repelled by Rocco’s brother Simon, whose own potential in the ring has been wasted. The influence of this film on the work of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola is obvious. Rocco is a definite must-see.

Also screening is The Damned (8:30pm, Fri, Aug 6) from 1969, an overblown but occasionally fascinating study of the collusion of the upper class with the riseof the Nazi party, viewed through the decay and collapse of a very twisted, very wealthy German family. Despite the inclusion of a character (played by Visconti’s lover Berger) doing a drag impersonation of Marlene Dietrich (as a birthday present to his father no less) and the Night Of The Long Knives massacre played as an over-the-top gay orgy, The Damned is confusing and somewhat tedious to watch. Naturally, the German bad-boy of cinema Fassbinder declared it his all-time favourite film.

But for gay audiences, it’s 1971’s Death In Venice (8:30pm, Thu, Aug 5) that holds the most allure. Simultaneously rapturous and haunting, the film features a tour de force performance by Dirk Bogarde, playing the sickly composer Gustav von Aschenbach who arrives in Venice and is immediately enthralled by the beauty of a Polish boy (the androgynous Bjorn Andresen). Based on the novella by Thomas Mann, Death In Venice is Visconti’s most personal film, and the director grapples with themes of aging, sadness and death as Aschenbach’s world is turned upside down by the power that resides in the casual beauty of youth. Time magazine called the film “irredeemably, unforgivably gay” (apparently not a compliment in the early ’70s, but a beacon to gay men to seek it out), and Death In Venice remains a profoundly moving experience, one that continues to resonate given today’s youth-obsessed gay culture.

Like all of Visconti’s films, Death In Venice is stunningly composed, rich in detail and demands to be savoured on the big screen.

LUCHINO VISCONTI.

$10.10 nonmembers; $6 members.

Till Sat, Aug 21.

Jackman Hall.

317 Dundas St W.

(416) 968-FILM.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra