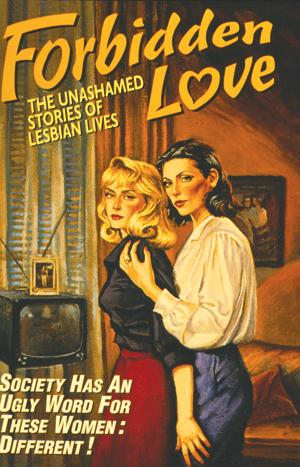

If you haven’t seen it before, Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives is a 1992 Canadian documentary by Lynne Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman that traces a connection between lesbian pulp fiction of the 1940s and ’50s and stories about real-life lesbians living in the time period. It’s a critically acclaimed film as well as an important historical document, but it’s also in danger of disappearing forever. Enter the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, whose exhibit Public Sins/Private Desires: Tracing Lesbian Lives in the Archives, 1950–1980 opened on June 22.

“The show started because Lynne Fernie went to one of our archivists,” explains Karen Stanworth, a York University professor and the exhibit’s curator, “and said it was the 20th anniversary of Forbidden Love this year and was there something the archives could do to help bring attention to the documentary? Because it only exists on VHS, and she wants to get it made into a DVD, but in order to do that, she has to get the NFB to renew all the music permissions, which will cost $20,000. So, there has to be a demonstration of interest in this material.”

To help drum up this interest, Stanworth and CLGA have assembled a huge amount of material, including cover art and excerpts from vintage lesbian pulp fiction, production photos and ephemera from Forbidden Love, and newly collected oral testimonies from Toronto lesbians. Stanworth helped to organize “a pre-event with some of the ‘older’ lesbians that we knew,” where the CLGA recorded the women’s stories. “They talk about going to the Parkside and the Fly by Night and the Bluebird and all these bars that were temporary, dingy and literally fly-by-night.”

Beyond being a remember-when for the older crowd, Stanworth insists the stories will be of interest to younger generations: “When we have young people listening to these stories, they’re like, ‘Wow! Oh, my god! It’s such an eye-opener!” For those who’ve grown up in a post-gay-rights world, it might be hard to imagine a time when your sexuality could make you an outlaw and being out at work was impossible. And while many of the testimonies are harrowing and traumatic, there are aspects of the world these women lived in that we could probably learn something from today.

“Many of these women had relationships with gay men, of varying sorts,” Stanworth says. “Their lives were much more intertwined than we often think of them now. They would go to bars with each other so they could dance with their girlfriends and boyfriends. But then they’d sit down at the table with two guys and two girls, so if there was a raid, they were safe.”

One of the most iconic aspects of Forbidden Love is its use of lesbian pulp fiction, a kitschy aesthetic that has had a renaissance in recent years, and Stanworth has made an effort to explore its contradictions. For one thing, the lurid covers often had nothing to do with the stories inside. “The artists didn’t necessarily read the books,” she explains. “They were just trying to sell novels.” Although originally conceived for a straight male audience, many lesbians turned to them because “it was the only place they could read about lesbian love.”

Public Sins/Private Desires sets out to shine a light on what homosexuality meant for a woman’s life in the not-so-distant past and, of course, to celebrate everything Forbidden Love achieved. “This is an important document in lesbian history, in Canadian history, and in sexuality studies across the board.” Let’s hope it finally gets that DVD release.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra