Andrew Lumsden just wanted to stand in the sunlight; the revolution could come on its own time. It was July 1, 1972. Queer London, like so many other cities around the world, had looked to the Stonewall Riots in New York City three years earlier and decided it was time they also took to the streets.

“They called [gay culture] the ‘Twilight World’ in newspapers, and that’s exactly what I felt,” says Lumsden, one of the first organizers with Gay Liberation Front in the U.K.

Lumsden and his queer peers were “blazingly angry” about police brutality and family rejection, he recalls. But marching from Trafalgar Square to Hyde Park that summer day, he wasn’t thinking about changing the law or even changing minds. “Other brave people were doing that. Our aim was to change ourselves, to lose all sense of shame and be proud, and that that would change other people,” he says. ”A Pride march was reclaiming the daylight, talking, embracing, kissing in front of people.”

Much has changed since that first Pride. Lumsden laments that the corporatization of the march has brought questionable partners to the event—a British arms manufacturer being one of the more terrifying examples. But that critical reclamation of dignity, year after year, remains.

As COVID-19 strikes Pride events off almost every June calendar this year, many LGBTQ2 people mourn that young queer people won’t have the opportunity to celebrate who they are at in-person events. Many groups like New York City Pride, which welcomed 5 million visitors for World Pride last year, will host virtual events. The biggest is a new digital event called Global Pride, featuring celebrities from across the globe; it’s scheduled for June 27.

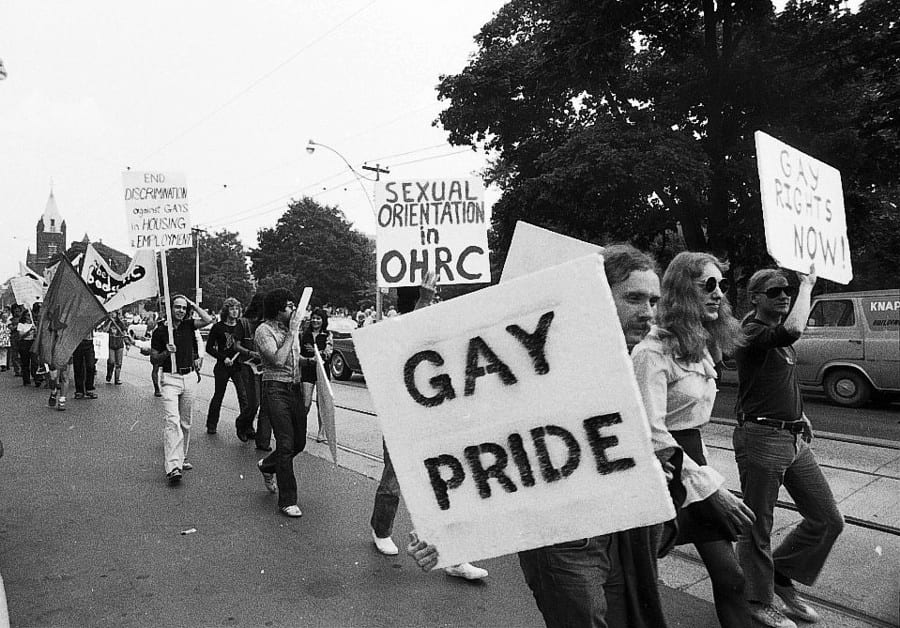

Demonstrators with London, U.K.'s Gay Liberation Front, 1972. Credit: Courtesy London School of Economics Library

As organizations usher in this new kind of Pride, there’s plenty to be lost in the shift from in-person congregation to virtual. But early Pride organizers say even these online events can help shepherd youth out of the shadows of shame.

Rev. Troy Perry is among the original organizers of Los Angeles’ first Pride celebration. Much of the celebratory nature of Pride we know today can be attributed to that 1970 event, when L.A. held the world’s first Pride parade (New York City held a Pride march the same day, a marked difference from L.A. as its event was a protest).

Perry, whose LGBTQ2-affirming church was still in its infancy, remembers getting the call from Gay Liberation Front founder Morris Kight to help organize a demonstration in L.A. in the wake of Stonewall. His immediate response was “no.”

“‘We’re going to hold a parade,’ I said,” Perry recounts. “‘This is Hollywood. Los Angeles has this culture of parades—whether it’s the Rose Bowl Parade, the Christmas Lane Parade in Hollywood…’ I just went down the list, and I said, ‘We’re gonna hold a parade.’”

Then-L.A. police chief Edward M. Davis didn’t share Perry’s jovial vision of Pride. Sitting at the police commission, Davis and other officials tried to dissuade organizers from hosting the event. “He said, ‘I’d rather have thieves and burglars marching than this group of people in the city,’” says Perry.

“Our aim was to change ourselves, to lose all sense of shame and be proud”

The commission told the group that if they wanted to host the parade, they would need at least 5,000 people marching and to put up two bonds. The first was a $500,000 bond for police overtime. The second? “One million dollars to pay for the property that’s going to be damaged when people throw rocks at you people and you duck,” Perry remembers a commissioner saying.

Organizers accepted the terms, thanked the commission, and left. Then, they called the American Civil Liberties Union.

ACLU attorney Herb Selwyn, a straight man, returned to the commission and asked them to drop the requirement for 5,000 marchers. When they agreed, he thanked commissioners and informed them that the city charter required the organizers to appear before the commission twice before taking them to court. Selwyn politely let them know that his clients had met that requirement. Now, they intended to sue.

The parade was scheduled for a Sunday; the hearing before the California Superior Court was the Friday before. “I’ll be honest, in our heart of hearts, we thought we were going to lose,” says Perry. Kight, Perry and L.A. Pride co-founder Rev. Bob Humphries prepared themselves for a loss just two days before the event.

But a judge asked the city if it required ad-ons for other groups. The city admitted it did not.

“I don’t care if you have to call out the National Guard, these people are going to have their parade,” Perry remembers him telling the city.

Organizers rushed to assemble a crowd, calling every organization and ally they could think of to fill the streets of Hollywood. That first parade, Perry looked out at a sea of thousands and was met with more dark sunglasses than he had ever seen—people who were too scared to fully show their faces. But it was a start.

“It gave people strength and hope, and we knew at the end of that parade we were a part of something historical,” he says. “It was just incredible.”

Those first Pride parades and marches spurred similar events across the globe, including in Canada. United Church minister and former politician Cheri DiNovo attended Toronto’s first Pride in 1971. DiNovo says that the event, which was deeply radical, was “pure joy.”

Pride in Toronto, 1981. Credit: Courtesy Peter Zorzi's 'On the Bookshelves' collection

But that “pure joy” of being fully out and embraced didn’t resonate across the entire queer community. Many LGBTQ2 people of colour didn’t feel reflected in those early events.

Craig Dominic, a gay DJ and activist in Toronto, remembers reading playlists from gay clubs in the 1980s. “All of it was just rock music or pop music,” he says. “And I’m thinking, what would it be like to be a Black person in my formative years trying to go out in Toronto in the ’80s? I would’ve felt like I was very alone and just not represented in any way.

Dominic had that experience himself in the late ’90s. He didn’t see Black drag queens or hear Black DJs at queer parties. He looked around Pride festivities and realized he wasn’t having the same experience as most people. There was no one there who looked like him.

In 1998, a group of friends in Toronto had the same thought and started Blockorama, a Pride celebration with Black diaspora DJs, dancers and drag performers. In the 22 years since, the event has grown so successful that it maxes out at 4,000 people and partygoers line up to get in. Dominic is now a co-organizer.

“The vibe in there is just community,” Dominic says. “The vibe in there is so intergenerational… I remember a couple years ago, I was DJing and we had kids dancing on the stage, and we also had someone who was in her 60s dancing on the stage. We have the entire swath of the entire community.”

“The thing about Blackness that I love is that we are just resilient: We can always find our way and make lemonade out of lemons and turn it into sweet tea.”

Of course, not every country started celebrating Pride in the ’70s. Buenos Aires, Argentina, first celebrated in 1992, a demonstration led by Carlos Jáuregui. Maria Rachid, a longtime lesbian activist, says even then only a few hundred people came, most of them masked so that they wouldn’t be recognized by family or co-workers.

“People were mostly surprised or curious, some people against it and some supportive,” Rachid says. “The press and the media covered it with sensationalist points of view.”

But the message of Pride had a healing impact on queer Argentinians, she says. The event grew into the thousands, doubling year after year. Today, Argentina is considered to be among the most LGBTQ-friendly countries in the world.

Rachid says Pride during coronavirus won’t be the same in Buenos Aires. Still, the event is traditionally held in November, not in June, so there is still hope for an in-person event. “Maybe masks will be useful again but for a different purpose,” Rachid jokes.

DiNovo sees the parallels between early Pride and today as deeply relevant. She was 21 when Toronto held its first Pride, and even then, she says, the community was divided between young radical organizers and those who simply wanted to fit-in.

“It’s between those two bursts of the movement, between those who saw acceptance as being the finale of the political process and those who say acceptance is not enough,” DiNovo says.

DiNovo has advocated against police presence at Pride, an idea gaining in popularity as massive protests against police brutality spread across the globe. Black Lives Matter, for one, will hold a protest on June 28 in honour of the Stonewall uprising on Long Beach, not far from L.A.

Performers on Pride Toronto's Blockorama stage in 2017. Credit: Nick Lachance/Xtra

Blockorama, which is officially part of Toronto Pride, will continue with a virtual event as well, says Dominic. “The thing about Blackness that I love is that we are just resilient,” he says. “We can always find our way and make lemonade out of lemons and turn it into sweet tea.”

As for organizers like Andrew Lumsden, he feels that something will be lost if Pride events stay virtual beyond 2020. The in-person demonstration of self-respect, for him, would be missing. “Well just now we mustn’t forget that our experience in London or in New York [during the pandemic] is the commonplace experience of nine-tenths of the people on the planet,” he says. “They can’t have a Pride march.”

Virtual events, however, might bring marches and parades to people who have never had them before for the first time, he notes. He imagines a kid whose family is rejecting them seeing the events for the first time.

“If just one such person hears bright-faced people saying it can be done and we’re doing it, that justifies an entire global virtual event.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra